Childhood and Community

Mākereti had many names over her lifetime. After her second marriage and during the majority of her time in England, she would have been known as Margaret Staples-Browne, and before that as Margaret Dennan after her first husband. However, Mākereti, the Māori transliteration of Margaret, was a name that she used throughout her life, this article will therefore refer to her as such throughout. Referring to her by her first name only is not intended as a sign of familiarity, only to allow for consistency in address, but for equality, other subjects in this article will be addressed in a similar fashion.

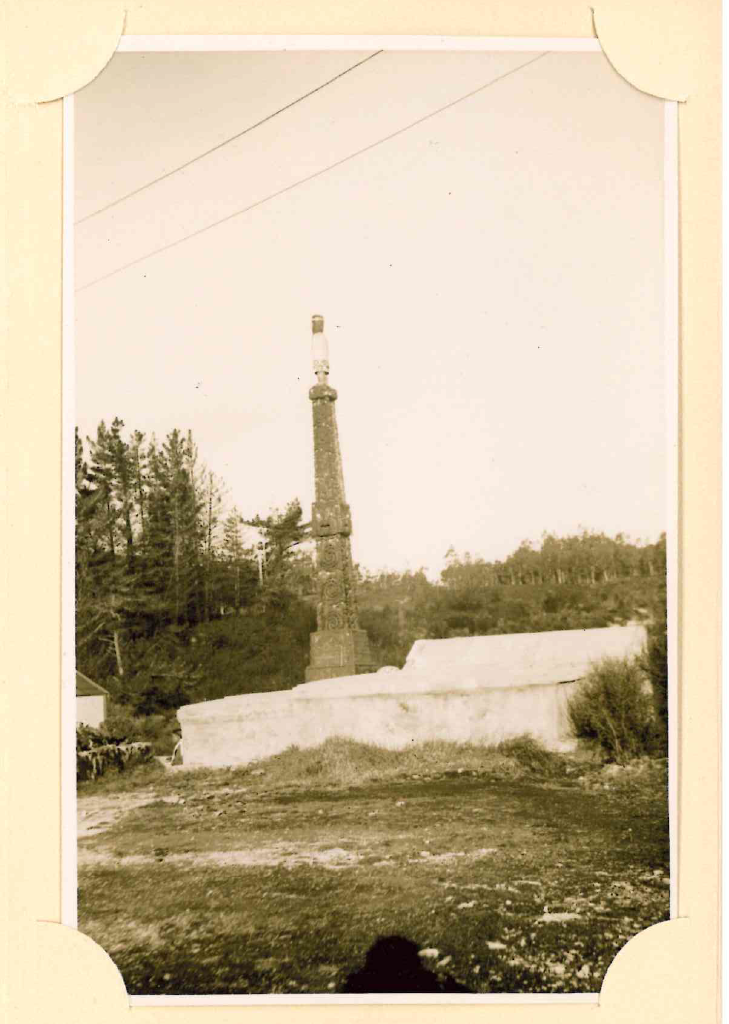

Mākereti was born Margaret Pattison Thom in 1873 in Aotearoa New Zealand. Her mother Pia Ngarotu Te Rihi, was descended from two hapū belonging to the Te Arawa federation (Ngāti Wahiao and Tūhourangi) and her father William Arthur Thom was a Pākehā storekeeper and solider in the Waikato Militia. Mākereti is often referred to as a Māori princess as she was the first born of a respected line of ancestors which can trace its roots back to chiefs from the original settlement of Aoteraroa New Zealand.

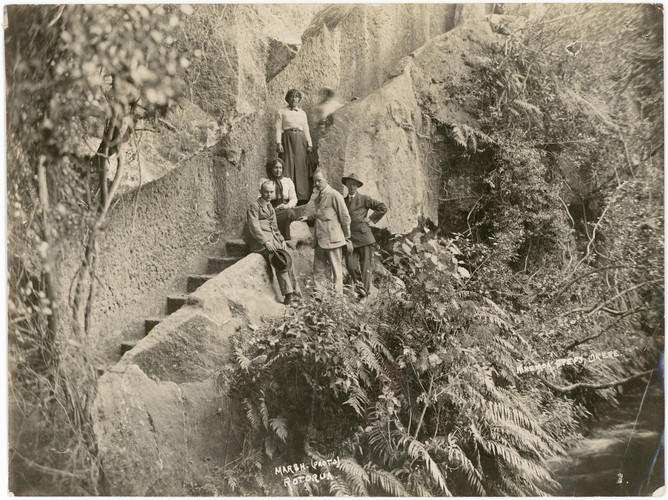

Her heritage made her very important to her tribe, and because of this she was raised not by her mother, but by her great uncle and great aunt (her maternal grandfather’s brother and sister). They educated her for the first nine years of her life in the Māori traditions and way of life. Yet with her dual parentage, Mākereti had the opportunity to combine her Māori education with a western one. For five years, starting at age nine, she began to learn English, through a variety of schools and private tutoring. Such a bicultural upbringing was rare at the time, so being able to adeptly navigate both Māori and Pākehā society was a signifcant advantage for Mākereti, and one she would later honour when she drew heavily on her childhood spent learning Māori customs from her elders to inform her research at Oxford.

![RS71235_PRM1998.277.98[cropped] RS71235_PRM1998.277.98[cropped]](https://www.st-annes.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/RS71235_PRM1998.277.98cropped.jpg)