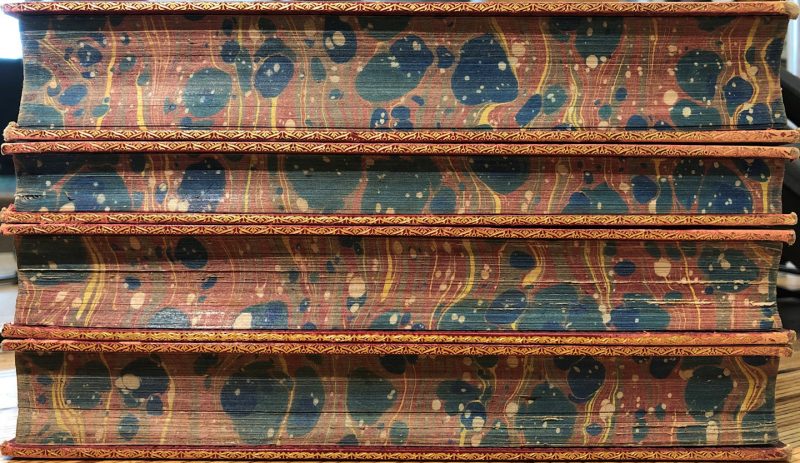

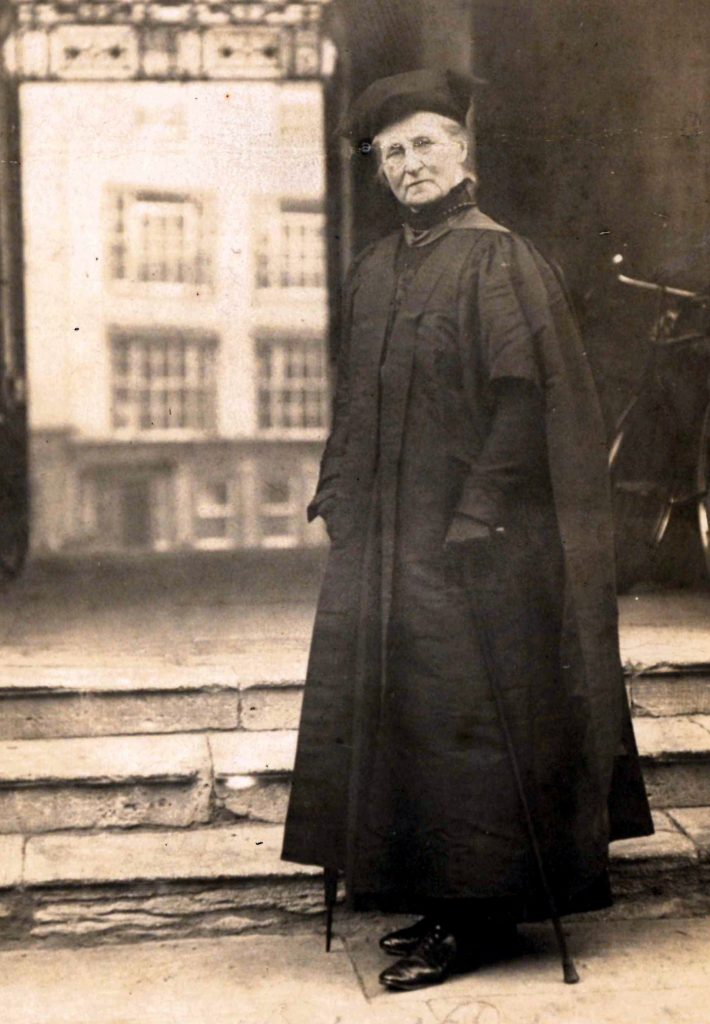

1873

Annie Rogers's Consolation Prize

Oxford school examinations were first opened to girls in 1870. Balliol and Worcester offered scholarships to the top scoring pupils but found themselves in an awkward position when the 'A M A H Rogers' who headed the list in 1873 proved to be a girl. Women could not be admitted to the University and she was presented with these four volumes of Homer instead.

The story caused a stir in the press and the University responded by creating 'Oxford Examinations for Women over Eighteen' (i.e. degree level) in 1875. Annie studied independently and took these in 1877 with first-class honours in Latin and Greek.

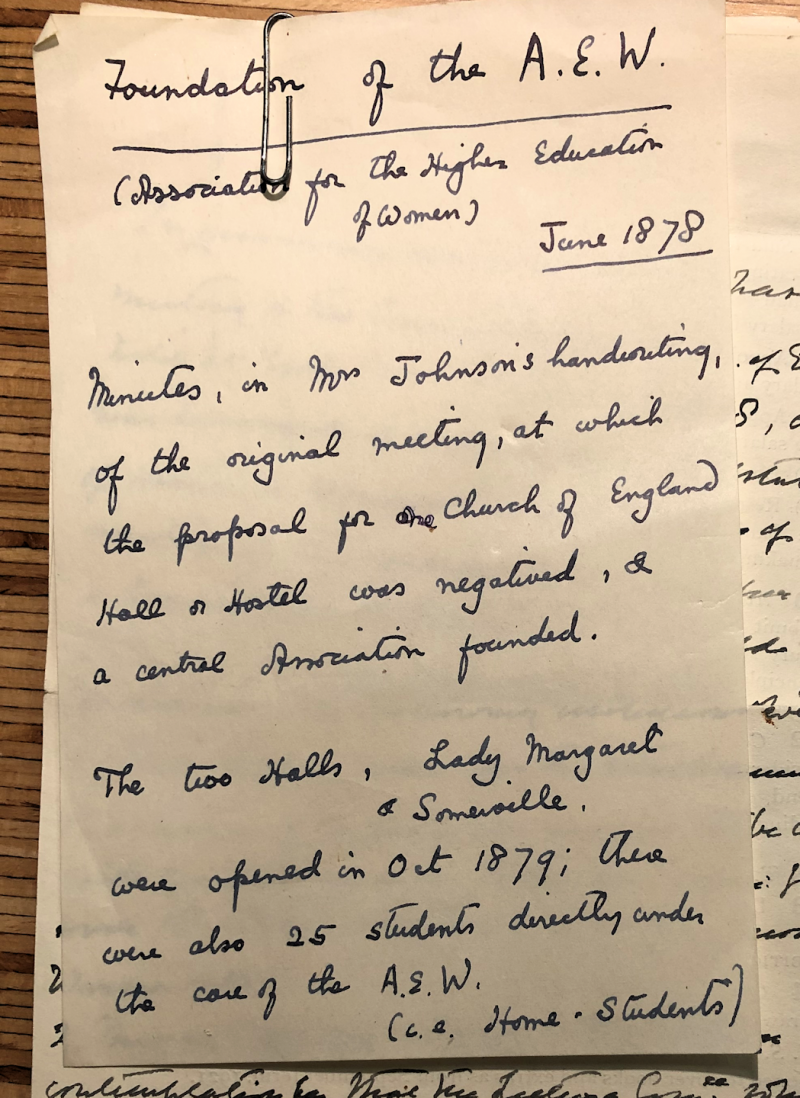

1878

Foundation of the A.E.W.

The Association for the Education of Women in Oxford (A.E.W.) was established in 1878 to support the growing numbers of young women around the city working independently towards degree-level exams.

The body primarily existed to provide a system of lectures for women but would also promote and protect their interests.

Lady Margaret Hall and Somerville Hall were opened as residential halls for women in 1879 (taking 9 and 12 students respectively) but there were a further 25 students living at home or in lodgings around Oxford. Initially under the direct care of the A.E.W., these students went on to form the Society of Oxford Home-Students: the precursor to St Anne's College.

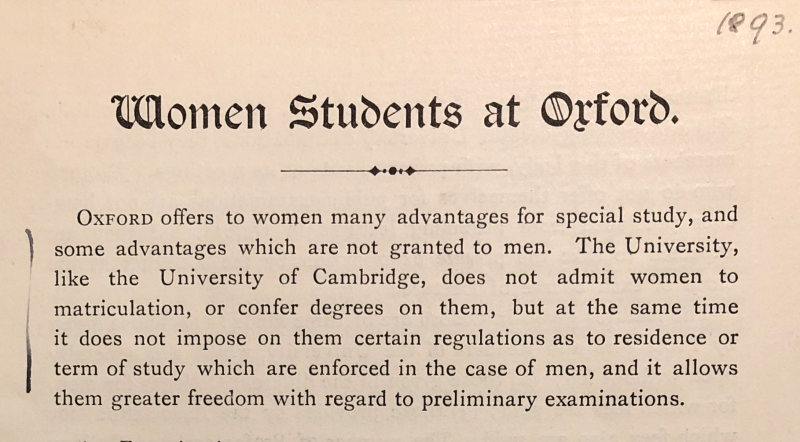

1893

Pamphlet

This pamphlet which advertised an Oxford education to women in 1893 reveals something of the complexity around degrees for women.

The decision to campaign for degrees was not always clear cut as some women feared the loss of freedoms with the tighter regulations around degree awards.

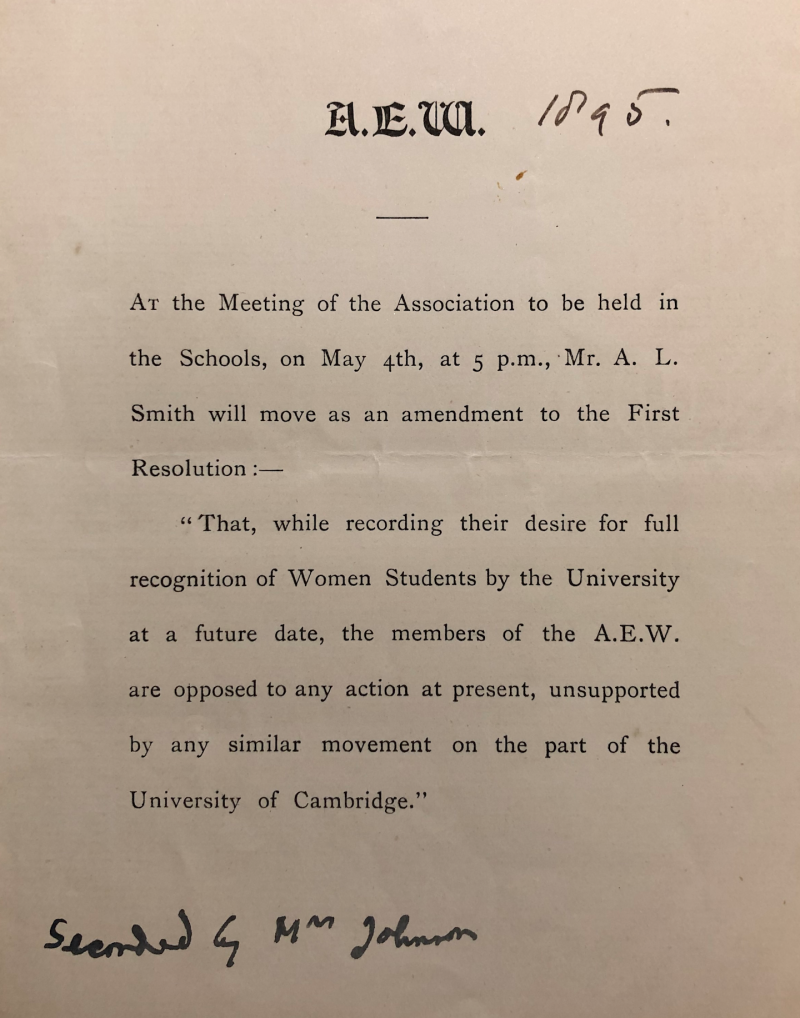

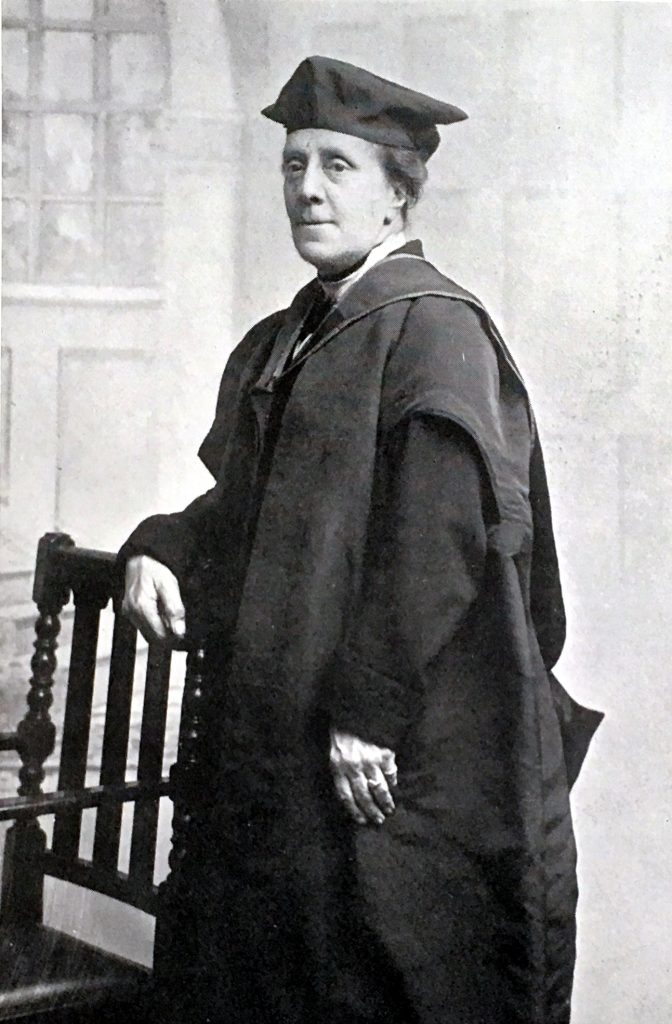

1895

Mrs Johnson

Bertha Johnson was the first principal of St Anne's (then the Society of Oxford Home-Students) and tirelessly administered the lives of generations of students from her own living room.

In 1895, she opposed the first move to award degrees for women as she felt that the timing wasn't right and that there was more to lose than gain.

Examinations could be taken in Modern Languages and English Literature but neither subject could be read as a degree. All B.A.s also had elements of compulsory Latin and Greek which she feared would be forced on her students.

Not everyone agreed with Mrs Johnson and although she was greatly respected, she also frustrated many supporters, including Annie Rogers, who by this time was a Classics tutor and secretary to the Society of Oxford Home-Students.

1896

Ladies not admitted

The first move towards the B.A. degree for women was defeated in 1896.

Though it had many supporters, there were those who hoped that the presence of women in Oxford might yet be a temporary thing. Others felt that opening degrees to women without residency requirements would be a case for doing the same for men, weakening the whole structure of the collegiate system and bringing the downfall of the University.

Thomas Case, later president of Corpus, wrote that "Sampson has dallied too long with Delilah". Among his many concerns, including over the frailty of women's bodies, was that this move towards B.A. degrees was a slippery slope. If the B.A. were granted then women would naturally seek the M.A., Fellowships and ultimately, the office of Vice-Chancellor.

The defeat came with a prevailing consensus in Congregation that granting women the degree now would hinder rather than help the cause of women's education.

1909

Curzon's 'Scarlet Letter'

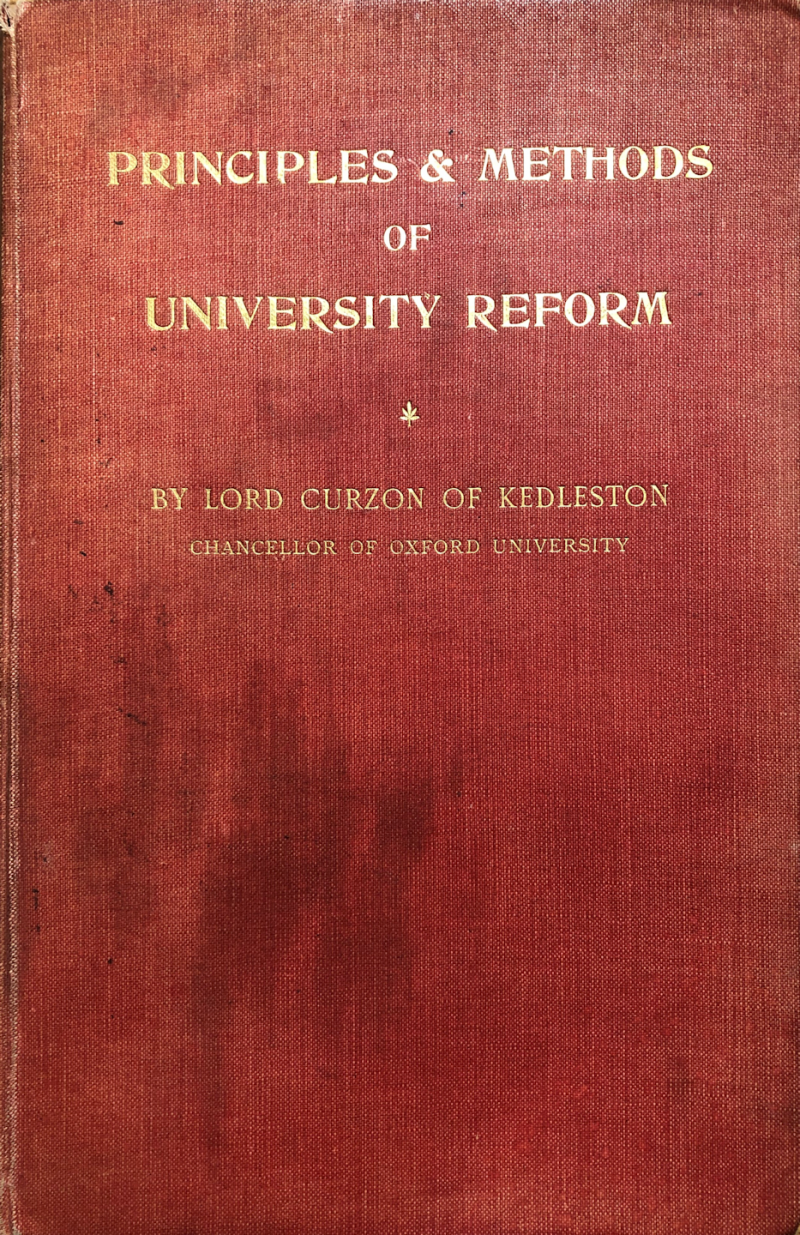

Progress was slow in the decade after defeat but with the passing of each year came a gradual change in attitudes. In 1907 the former Viceroy of India, George Curzon, was appointed Chancellor of the University.

More active than many previous holders of the role, he threw himself energetically into university reform and in 1909, published his Principles & Methods of University Reform.

This 'Scarlet Letter', so called because of its striking red binding, laid out a great number of suggested reforms to the University, among which was the opening up of the degree to women students. Curzon wrote that this would be 'in the interest of all the parties concerned' and pointed out that every other English and Scottish university had, aside from Cambridge, already done so.

Curzon's support gave renewed strength to a movement that had been largely dormant for over 10 years. However, even he had his limits and made clear that he objected to women joining Convocation, Congregation or any governing bodies of the University, as well as the cause of women's suffrage.

1910

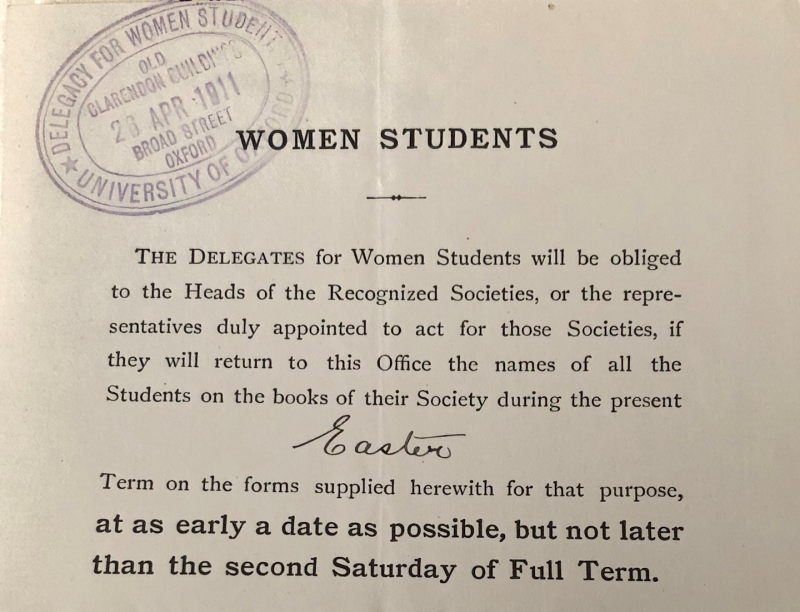

Delegacy for Women Students

In 1910 a new Delegacy for Women Students was formed by the University. The first official body (although integrated, the A.E.W. had never been official) to manage the education of women, it also took on responsibility for the Home-Students.

Mrs Johnson was reconfirmed as Principal and so became the first female member of any Delegacy and the first woman to be appointed by the University to an office.

1914

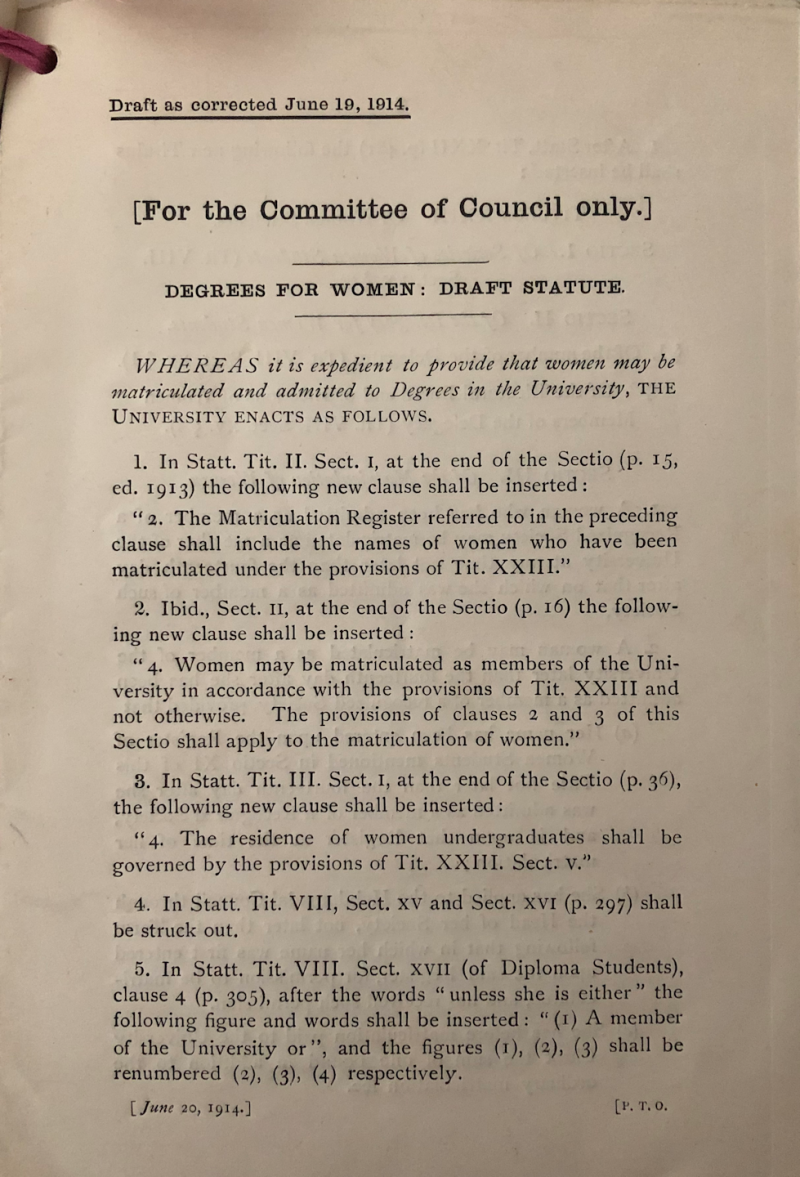

Draft Statutes

By 1914 draft statutes had been prepared in great detail. Annie Rogers was known for her statute expertise and indeed her posthumously published book Degrees by Degrees is prefaced with a line from the book of Psalms:

'Thy servant is occupied in thy statutes' -- Ps. 119, v. 23

Progress might have moved a good deal faster at this final stage had the First World War not broken out the following month, suspending the committee scrutinising the statute.

1918

Votes for Women

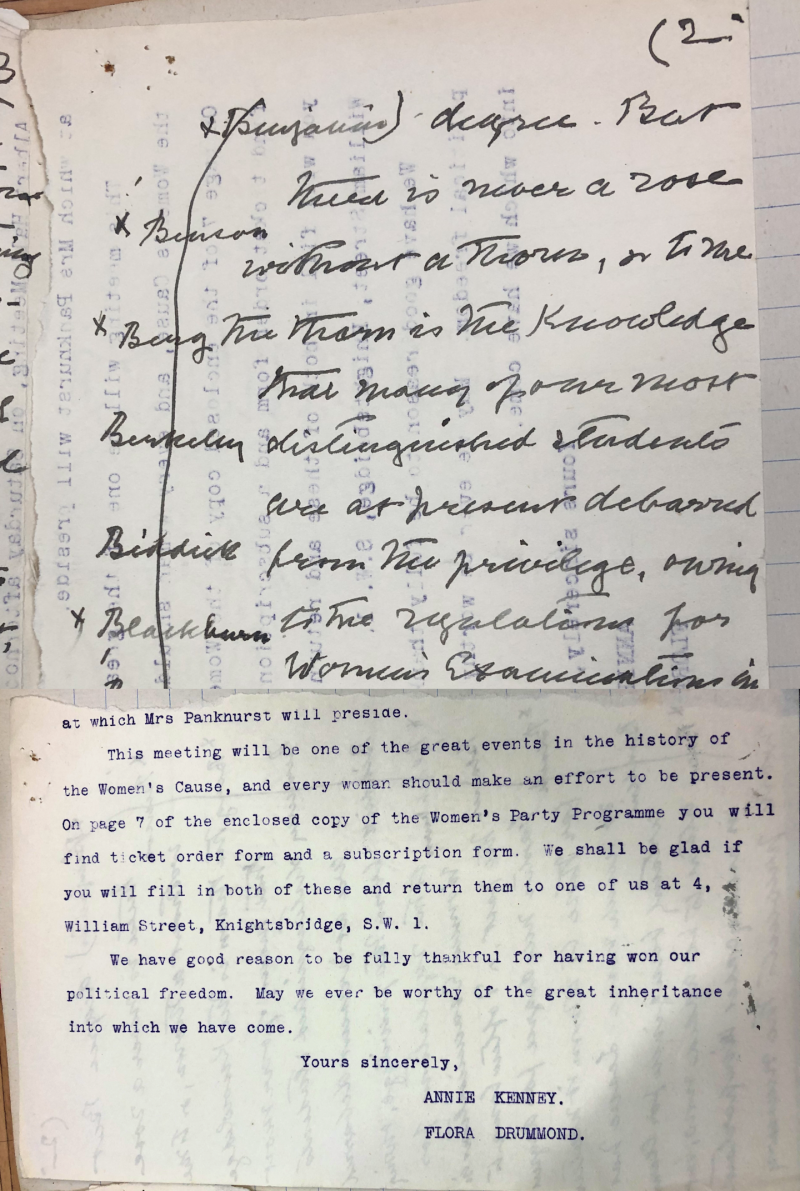

Mrs Johnson wrote these scribbled notes about the degree on the back of an invitation to a celebration of Women's Suffrage. Annie Kenney and Flora Drummond were prominent suffragettes.

With the war over and some women now given the Parliamentary vote, the degree question could only go one way. 'The War', wrote Annie Rogers 'had made a peaceful change in the status of women which seemed incredible (before it)'.

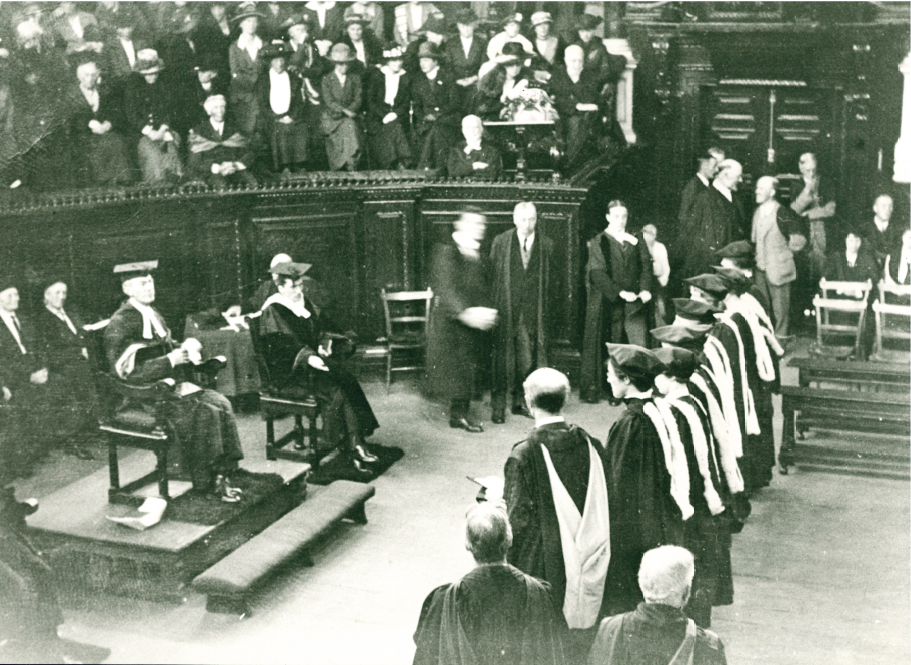

1920

The Degree

It was another eighteen months before statutes had been sufficiently scrutinised and a motion was moved in Congregation on 17 February 1920.

After so many years of build-up, there was no opposition raised. In fact, when the motion came, it also specified that women should be members of Convocation and further statutes proposed eligibility for Council, Congregation, Faculties and Boards of Faculties.

Two weakly defended amendments were defeated and the statute finally passed Congregation on 4th May 1920 and Convocation on 11th.

The statute came into effect on 7th October of the same year and the first matriculations of 129 women were held the same day. Alongside the statue came a number of decrees to award degrees to former students who had met all of the requirements. For a number of years afterwards, former students would return to Oxford and pay their fees to finally matriculate and graduate on the same day.

None of the principals of the women's societies had taken the necessary examinations to earn Oxford degrees but were awarded M.A.s by decree on the first graduation day of the term, 14th October. Mrs Johnson was the first among them.

This exhibition was curated by Duncan Jones, Reader Services Librarian.

All objects and photographs are from St Anne’s College Archive.