We have recently been cataloguing a set of books that belonged to the late Phyllis Margaret Handover (1923-1974) who was a St Anne’s alumna. Handover published on printing and typography and worked as assistant to Stanley Morison (1889-1967), developer of the Times New Roman type and himself an extensive writer on printing and typography.

Among the books in the bequest are a number that belonged to Stanley Morison and which he had evidently passed to Handover during their years working together. One of the first to be catalogued was Morison’s copy of An enquiry into the nature of certain nineteenth century pamphlets (1934) by John Carter and Graham Pollard. The front flyleaf is signed by both authors with a presentation note to Stanley Morison. On the opposing page (inside the ‘upper board’) is a draft menu and seating plan for a dinner in which each dish involves a play on words. When cataloguing the book, we noticed that the book had the distinct feel of having been in, or too near to, a fire. The paper is crisped and brittle and the binding carries blackened edges.

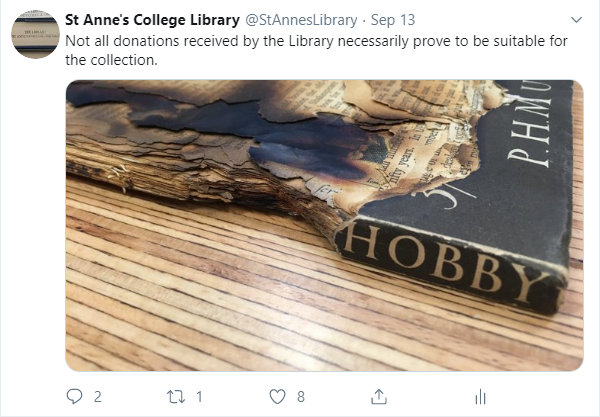

This wasn’t particularly interesting until a much more blackened book appeared, one which had very definitely been on fire at some point during it’s history. At the time, we even made light of it on social media:

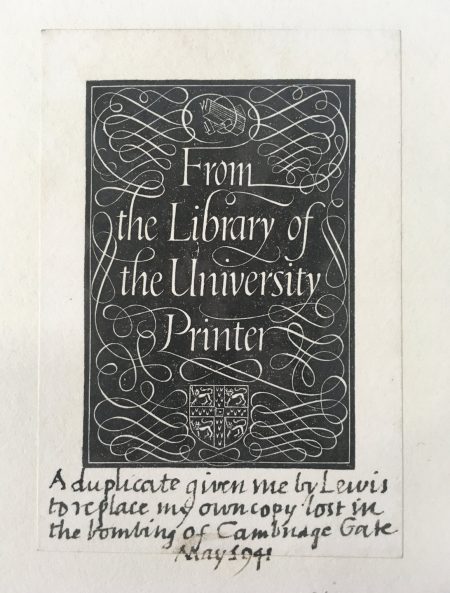

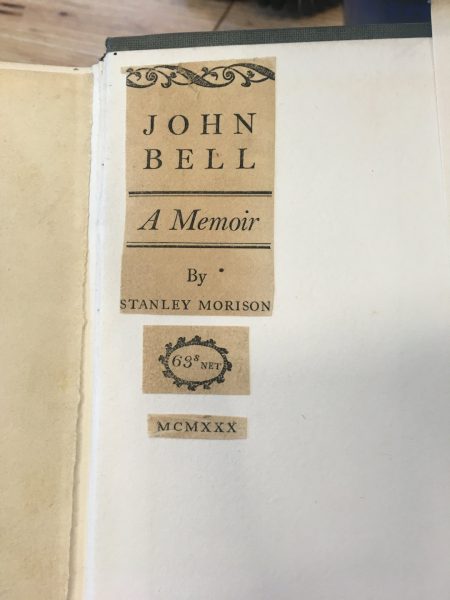

The significance of these burned books only came to light, however, when another book by Morison was catalogued; one which carried a surprisingly descriptive bookplate:

The book carrying the plate is a copy of John Bell, 1745-1831 : bookseller, printer, publisher, typefounder, journalist, &c. (1930). As it was written by Morison himself, he’d evidently lost his only copy in the bombing. In fact, inside the back and on the half-title page, Morison has pasted in fragments from the dust jacket of another copy, presumably his own bombed one.

What else was lost in this bombing and what were the circumstances? Fortunately Morison himself gives a description of it in the introduction to another book ‘Black-letter’ text (1942).

The two page introduction carries a vivid account of being in wartime London at the height of German bombing. Written a year later, Morison’s words are very matter of fact and seem to convey more annoyance at the destruction and interruption to his work than any fear for himself. There is even a wry humour is his treatment of the events.

“In the leisure hours of recent years I have been revising papers on historical aspects of calligraphy and typography…there were interruptions. Regent’s Park, where I live, is a district favoured by the enemy.” [p.3, ‘Black-letter’ text]

He recounts staying at a friend’s house in the Regent’s Park while repairs to his bomb damaged flat in Cambridge Gate are carried out. Six months later and just days before he is due to move back into his flat:

“…it pleased the Luftwaffe to effect the most spectacular and destructive of all the air raids that had taken place over London since the war began…I was half in bed, trying to read, at the time. I knew well enough what was the matter. A furious banging on the front door confirmed that the place was on fire” [p.3]

Having dealt with the fire at his friend’s house he discovers that his own flat in Cambridge Gate, so close to restoration, is on fire.

“The draught let in by my opening the door fanned a pair of handwoven curtains into a beautiful flame. The illumination opened to my view a confused mass of burnt carpet, broken glass, lime and plaster from the ceilings, upturned book cases; the whole sodden with torrents of water still descending from the roof and upper floors. Three rooms of my flat, with all their contents, had disappeared as if they had never been. Everything had fallen into a vast cavity burnt out in the back basement, some thirty feet below. I was able to distinguish metal bookcases which, until then, had accommodated a large number of political and other books. These had all gone. My run (to the last livraison) of Leclercq and Cabrol’s Dictionnaire, Hastings’ Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics, a set of liturgical books, together with collections on the history of printing and of journalism had been destroyed, and much else… Works larger than folio which were not in these rooms I was able to save. In the torrent still streaming from the firemen’s hoses, I was able to shift Chatelain, P.C.L.; Lowe, C.L.A.; Rand, Survey of Tours; Zimmerman, Vorkarolingische Miniaturen. Other portfolios I kicked into shelter under my large dining table. Dozens of octavos and quartos had already been badly scorched and then soaked; the vellum leaves of the Canon of the Mass in Stuchs’ Benedictine Missal (Leipzig, 1501) were congealed; the leather binding of Louis XIV’s folio Médailles of 1702 was ruined. Much good stuff was done for.” [p.4]

The bulk of Morison’s surviving papers and books are now in the archives at the University of Cambridge but the account of the damage makes for some distressing reading. Unfortunately, from what we can tell of the badly burnt P. H. Muir’s Book-Collecting (pictured above) it wasn’t published until 1944 and so cannot be one of the books damaged in the Cambridge Gate bombing.

Bibliography

- Carter, J., & Pollard, G. (1934). An Enquiry into the Nature of Certain Nineteenth Century Pamphlets. London : Constable & Co Ltd. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/q6b76e/alma990101358340107026)

- Morison, S. (1942). ‘Black-letter’ text. Cambridge : Printed at the University Press. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990119142780107026)

- Morison, S. (1930). John Bell, 1745-1831 : Bookseller, Printer, Publisher, Typefounder, Journalist, &c. Cambridge : Printed for the author at the University Press (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990119142200107026)

- Muir, P. (1944). Book-collecting as a hobby, in a series of letters to Everyman. London: Gramol Publications. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990119352990107026)

This article was written by Duncan Jones (Reader Services Librarian).