1896-1989

Iris de Freitas Brazão

With thanks to the Archives at the University of Aberystwyth for the images used in the header and thumbnail for this article. (Above and right.)

A note on Guyana:

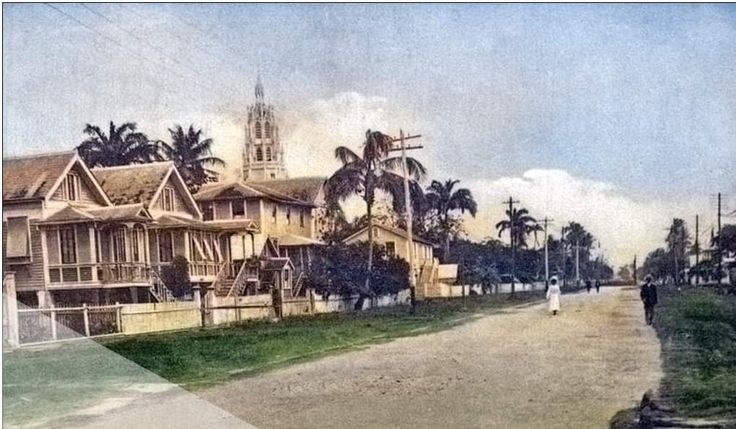

Iris spent most of her life living in the country that was then the colonised nation of British Guiana. This country has since won its independence and is now called Guyana. As independence did not come until Iris was almost 70 and already retired, in this article it is referred to throughout under its old name ‘British Guiana’, in order to highlight the adverse colonial conditions that Iris, as an illegitimate woman of colour, so adeptly navigated.

Early Life and Education

Iris de Freitas Brazão was born on October 29 1896 in Bay St, Kingston, Bridgetown, Barbados. Her parents were Manuel de Freitas, a businessman who started out as a leather and bootmaker and later expanded to other ventures, and Amanda Brathwaite about whom little is known other than that she was a mixed-race Barbadian local. (Brathwaite is a prevalent name on Barbados and is likely to derive from the slave-owning family who operated a plantation on the island.) Iris’s parents were not married, a significant social transgression at the time which would have an impact on Iris’s societal status. It seems, however, that she was acknowledged and supported by her father, Manuel, despite him having two legitimate children with his wife Antonia (and various other illegitimate offspring).

Although Iris and her father certainly remained close, her mother would have been Iris’s primary caregiver growing up, and together the two moved from Barbados to 1 Lombard St, Georgetown, British Guiana, sometime between 1897 and 1910, whilst Iris was still quite young. She later admitted that she had no early childhood recollections of Barbados, although she would return later in life to further her education.

Her studies most likely began in British Guiana where we think she was first privately tutored, she then attended the Roman Catholic school St Ursula’s in Georgetown from 1910-1916. There was also a more prestigious sister school, St Rose’s, that Iris’s father would have been able to afford the fees for. However, the parents of girls at St Rose’s would not allow their white daughters to associate with girls of a lower social standing. Since Iris was both mixed-race and illegitimate, she would not have been able to attend. Despite these barriers, Iris continued with her education at St Ursula’s and developed ambitions, not of a legal profession, but of a life on the stage. In her first role in a school production, Iris played the part of a lawyer, but unfortunately also discovered she suffered from stage fright, putting an end to her childhood dream of becoming an actress.

Iris completed her education at St Ursula’s in 1916, but although she was at this point nearly 20 years old, she did not immediately start university due to travel restrictions as a result of the First World War. Instead, she returned to Barbados, the island of her birth, and studied for two years there, at Queen’s College.

Flu and False Starts

Towards the end of the First World War in 1918, she travelled to Canada to study modern languages at St Hilda’s College (part of Trinity College) at the University of Toronto. During her stay, the college was briefly closed for a month due to the Spanish Influenza epidemic from October-November 1918, an experience perhaps eerily familiar to modern students. She eventually left Toronto before completing her studies or sitting any exams. We can only speculate as to the reason for Iris’s premature departure from Toronto, as she left no record indicating the reason for her decision. She may have faced significant difficulties in Canada at that time due to her mixed-race heritage, or she may have always intended to study in the UK, with Toronto being her only other option when current events stood in her way.

In fact, we do know that Iris had initially applied to study at what was then the University College of Wales (now Aberystwyth University) in 1917, perhaps on the advice of the English mistress at Queen’s College in Barbados, Miss Jones, who was an alumna of the university. Unfortunately, travel to Wales would have required her to cross the Atlantic, which was then considered a danger zone due to the ongoing war, so she was not given permission to travel at the time. Upon leaving Toronto, however, the opportunity to study in Wales was once again open to her.

Undergraduate Studies in Wales

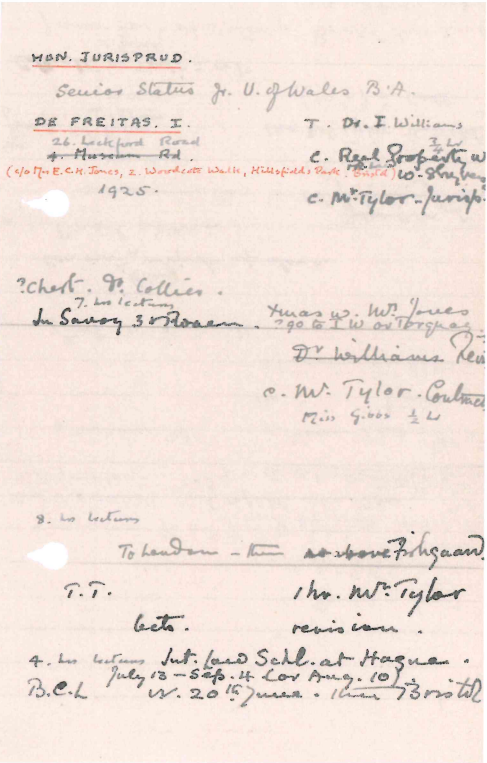

Higher Education in the early 20th century was not quite so inflexible as it is today, and Iris’s studies reflect this in the variety both of subjects of study, but also the number of institutions at which she studied. Iris was able to conduct a number of different courses of study concurrently, so painting a clear picture of where she studied when can prove a bit of a challenge. (See our timeline at the bottom of the page for a visual aid.)

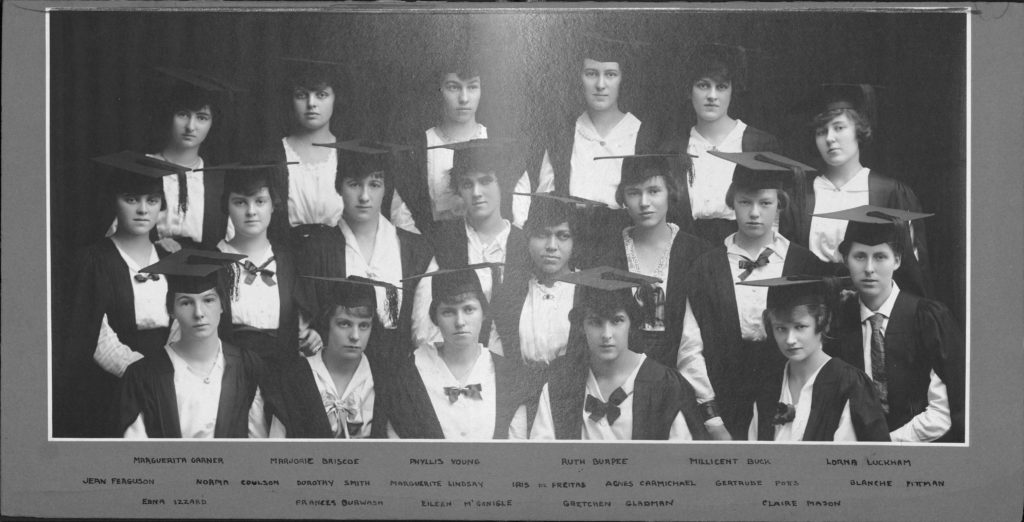

Iris began her tertiary education at Aberystwyth in January 1919. She completed courses on a wide variety of subjects including, Latin, Modern Languages, Economics, Jurisprudence, and Botany. We also know that she was active outside her varied academic interests; she was a member of the literary and debating society, as well as the law society at Aberystwyth. Iris also went on to become the president of the Women’s Sectional Council and the Wales Students’ Representative Council, a precursor to the Students’ Union. After she completed her BA in July 1922, her tutors were extremely complementary in the references they gave her. One asserted that she was, “one of the best law students we have ever had in the college.”

Success and Stigma

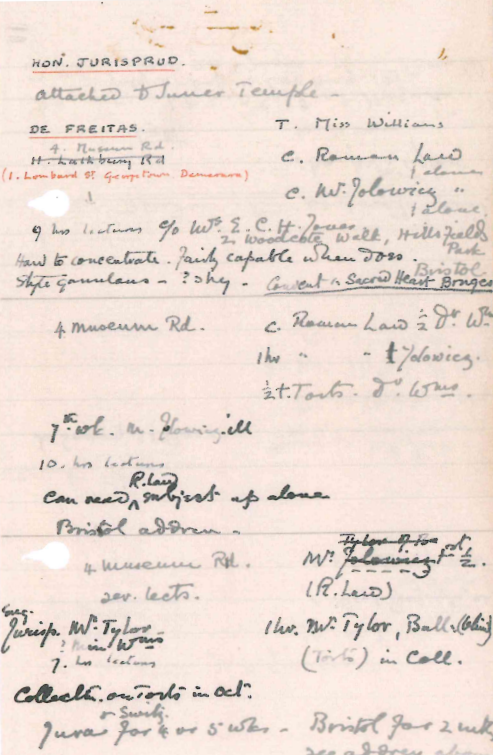

Although she registered for courses in English law and Jurisprudence at Aberystwyth with a view to qualifying for an LLB, with these glowing references in hand, Iris also travelled to England and enrolled with the Inner Temple Inns of Court in September of 1922 (although she would not sit any examinations for the bar until 1926). She then continued to Oxford where she matriculated with the Society for Oxford Home-Students (now St Anne’s College) a year later in 1923. It was relatively common at the time for Oxford students to study for the bar concurrently with their degree, as it was believed that an Oxford degree would more than adequately prepare them for the bar exam. Her acceptance at Oxford meant that she was exempt from her studies in Aberystwyth while she completed her new course.

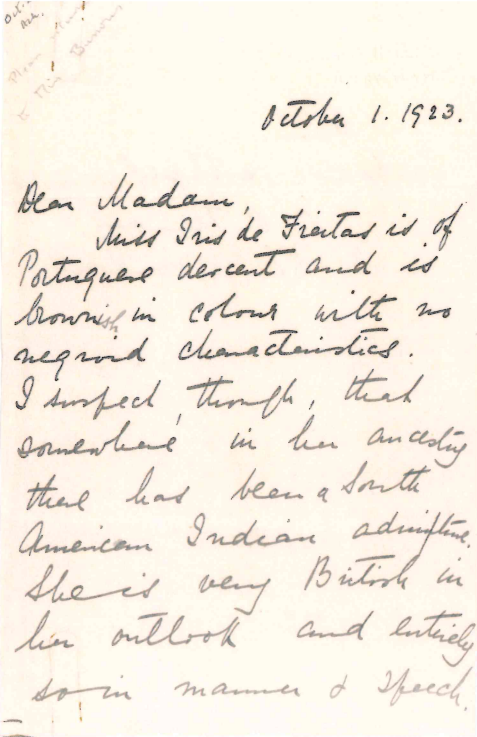

Despite her academic success up to this point, Iris’s race was not entirely overlooked during her studies in Wales and in England. Her student file contains a note from the Senior Warden of her halls of residence in Aberystwyth discussing Iris’s ancestry. It assures Miss Burrows, the then Principal of the Home-Students, that Iris was “of Portuguese descent and is brownish in colour with no negroid characteristics”. She goes on to state that she “suspected … that somewhere in her ancestry there has been a South American Indian”. She finally noted that Iris was “very British in her outlook and entirely so in manner of speech.” It goes without saying that white students were unlikely to have had their ancestry discussed in such detail as part of their admission to the University, although it is not recorded whether this information was solicited by Miss Burrows, or offered unprompted as part of a general request for information on Iris’s studies at Aberystwyth.

Studies in Oxford

Because she had already completed a BA in Aberystwyth, Iris was able to matriculate at Oxford as a senior student, which meant she could complete her next course of study, a second BA, in just two years. Her academic report in her first year notes that she found it “hard to concentrate” but acknowledges that she was “fairly capable” when she did. Another note indicates that she was rather “shy,” which along with her earlier discovery of stage fright suggests that Iris’s personality outside the courtroom may have been less imposing than the skilful lawyer we see her become once she began advocating.

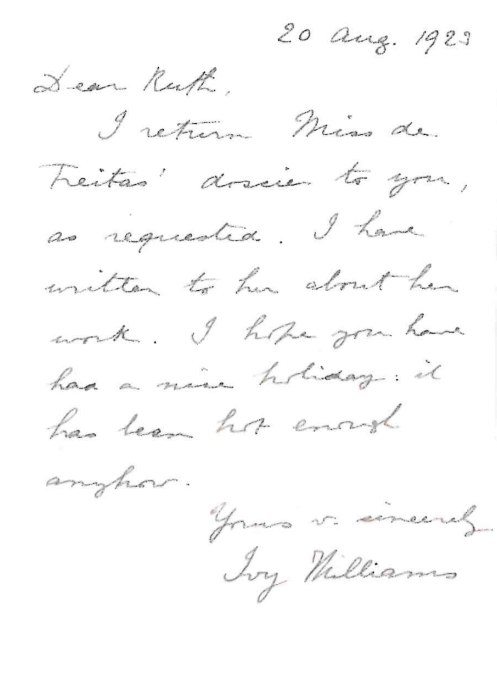

Her report also tells us that she was taught by another Home-Students alumna, Dr Ivy Williams. This is significant as Ivy was the first woman to be called to the bar in England. In fact, she had done so just the year beforehand, in 1922, becoming somewhat of a media sensation, so it was likely that Iris would have heard of her new tutor’s achievements and may even have been influenced in her legal ambitions. In fact, Iris had registered with the Inner Temple Inns of Court the same year that Ivy was called to the bar there. Sadly, we have no record of any correspondence between Ivy and Iris, although we do have a note from Dr Williams to another member of staff indicating that she was writing to Iris about her work in the months before she began her studies.

Legal Ambitions

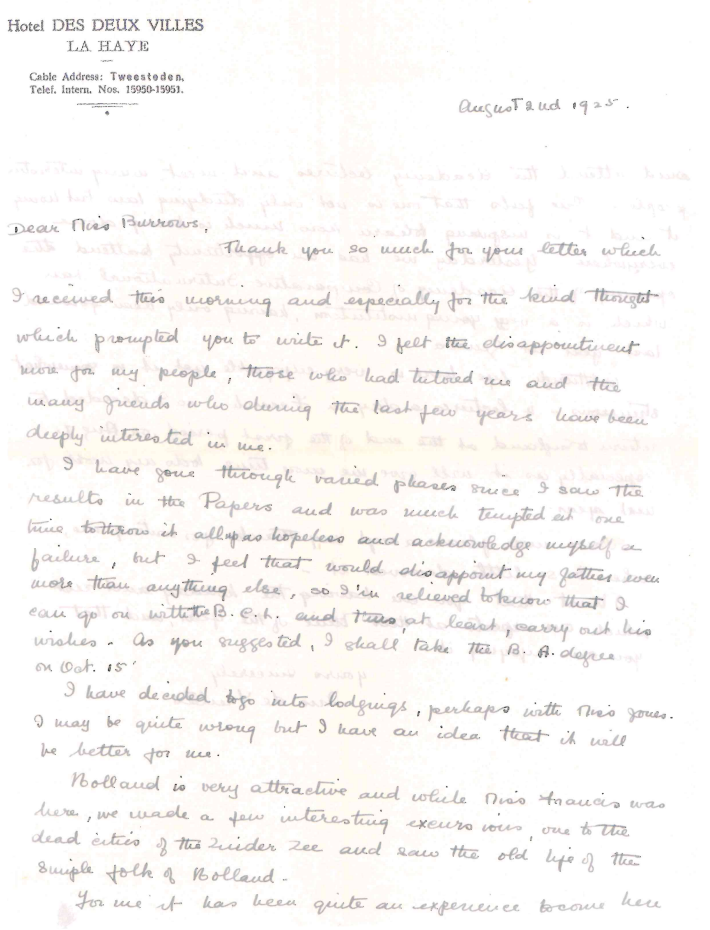

Iris completed her final exams for the BA in jurisprudence in 1925. She graduated with a third-class degree which at the time was a passing grade. Despite this it appears that Iris was very unhappy with her results as she notes in a letter to the Principal in August of that year. She wrote:

“I have gone through varied phases since I saw the results in the Papers and was much tempted at one time to throw it all up as hopeless and acknowledge myself a failure, but I feel that would disappoint my father even more than anything else, so I’m relieved to know that I can go on with the BCL and thus at least carry out his wishes.”

By all accounts, Iris’ father Manuel had been a significant influence in terms of her education and legal ambitions; it was he who had funded what would have been a very expensive education for any child, let alone an illegitimate daughter. Iris’s legitimate brother, Stanley McDonald de Freitas, had also qualified as a barrister a few years previously, in 1921, so Iris may have been determined to make both her father and brother proud when it came to her legal studies.

Despite what Iris may have considered a setback in this matter, she jumped straight into her next course of study, Oxford’s infamous BCL, a postgraduate legal qualification which had a reputation, both then and now, as being one of the most difficult courses of study one could undertake. Nevertheless, she persisted and in just one year she had obtained her BCL degree and gone on to complete all of her bar examinations. She then concluded her studies for the LLB at Aberystwyth, graduating in 1927, and finally she fulfilled the attendance and dining requirements at Inner Temple, allowing her to be called to the bar in 1929.

Return to British Guiana

Upon completing her legal education, Iris returned to the Caribbean, stopping first in Barbados to become the first woman to be called to the bar there. She then made a stop in Jamaica, before returning home to British Guiana to live with her mother. Following her call to the bar, she made her first appearance in court in November 1929, making her officially the first female lawyer in the commonwealth Caribbean. A few years later she became the first woman to advocate in a murder trial in British Guiana, sixteen years before Helena Normanton prosecuted her pioneering case in the UK. Iris was the attorney for the defence in the 1932 case and was able to see her client, Gangadeen, acquitted, winning praise from the judge for her advocacy in the case. She went on to join the civil service as a Temporary Legal Assistant within the Attorney General’s Chamber, and from April 1934 she served as the first female crown prosecutor in British Guiana. Iris’s other career highlights included working for the Franchise Commission, the Public Service Commission, and later as the Legal Advisor to the Governor of British Guiana.

Marriage and Controversy

In 1937 Iris married fellow lawyer Alfred Casimiro Brazão, who at the time was a magistrate, but went on to become solicitor general. In a typical fashion, their marriage had little impact on his career, yet for Iris it became a point of contention as married women were only able to continue working within the civil service if granted special permission. It was such an issue that the (all male) Legislative Council of British Guiana discussed her continued employment and use of her maiden name (de Freitas) professionally in 1940. In their deliberations they mentioned Iris’ legal right to practice under her maiden name, established by Helena Normanton in 1924 in the UK. Thankfully Iris was defended in the matter by the then Attorney General and subsequently continued to serve as Clerk to the Attorney General under her maiden name until 1953.

Death and Legacy

Her break from work in 1953 was due to the tragic death of her husband while he was away on business in England. She had lost her father 8 years previously in 1945, but Alfred’s death left Iris distraught and she went to stay with family friends for months afterwards to recover.

She did eventually return to work (opting now to use her married name, Brazão, perhaps in memory of Alfred) however, only a few years later, in 1957, the retirement age for those in the civil service in British Guiana was set as 55. Iris who would have been over 60 at the time would have likely been asked to retire. Despite her retirement, Iris still continued to influence the future of British Guiana. It was at this point that she spent time as part of the Public Service Commission making recommendations on the appointment and training of new staff in the civil service in British Guiana. In the run-up to independence there was a move towards employing more Guyanese staff in key posts and Iris would have played a significant role in ensuring this was the case.After ending her time on the Commission, it is said that Iris liked to garden and volunteer for local institutions such as the public library and the Red Cross. She likely also spent time with her mother, who reached the impressive age of 103 before passing away sometime around 1978. After a peaceful retirement of over 30 years, Iris also died at the age of 92 in 1989.

Although her family and community in Guyana remembered and honoured her after her death, elsewhere Iris’s incredible story was forgotten over the years. Thankfully the chance discovery of a postcard with her photograph by Aberystwyth University back in 2015, as well as the work of historian Dr Joanne Collins-Gonsalves who published a comprehensive biography on Iris last year, has brought Iris’s achievements rightfully back into the limelight.

Timeline

This article was written by Alice Shepherd (Library Assistant).

Sources and Further Reading

Books

- Collins-Gonsalves, Joanne, Iris de Freitas : Legal Luminary and Trailblazer, Atlantic Academic Publishing, 2023 (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma991026811521407026)

Articles

- Iris de Freitas Brazao, Women of West Wales (https://woww.narberthmuseum.co.uk/iris-de-freitas-brazao/)

- Iris de Freitas Brazao, Black History Wales Resources (https://blackhistorywales.org.uk/resources/resource/iris-de-freitas-brazao/)

- Aberystwyth University honours first female lawyer in the Caribbean, Aberystwyth University (posted 7th March 2016) (https://www.aber.ac.uk/en/news/archive/2016/03/title-181429-en.html)

- Iris de Freitas – an amazing lady, Family de Freitas (https://crescentbeachcayman.com/defreitas/iris-de-freitas—an-amazing-lady.html)

Videos

- Caribbean Court of Justice, Pioneering Caribbean Women Jurists “The Early Pioneers”, YouTube (posted 20th December 2021) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8TLR1nFJ8-M&t=120s)