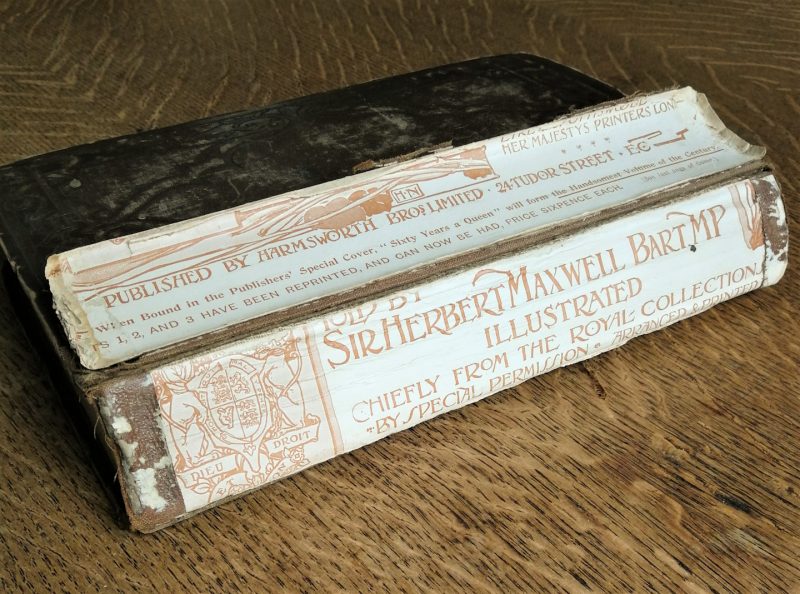

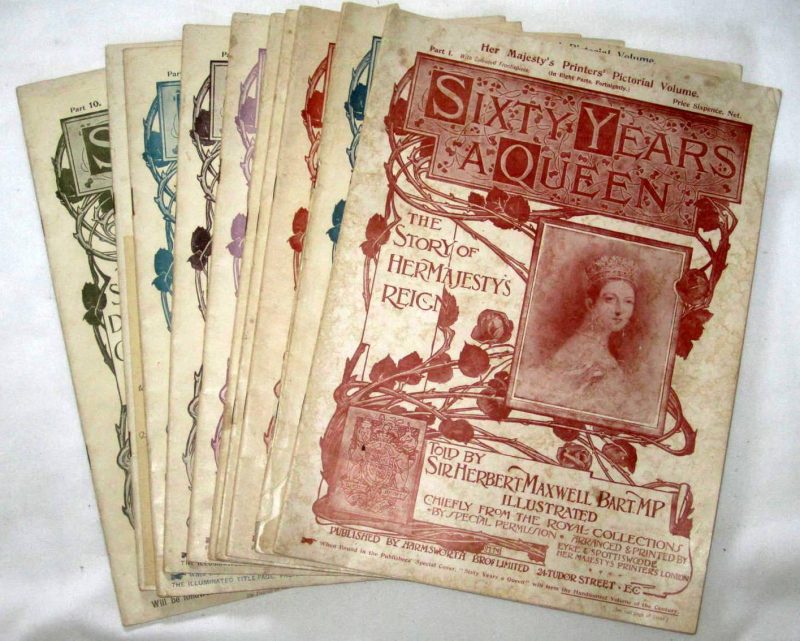

Master Humphrey's Clock

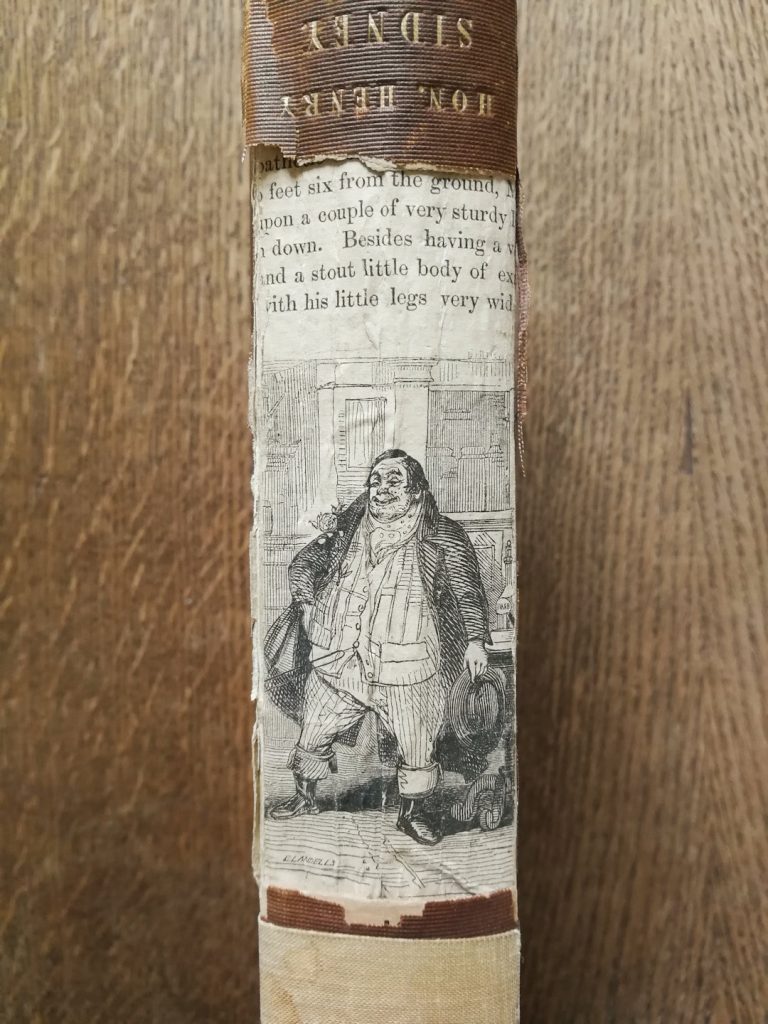

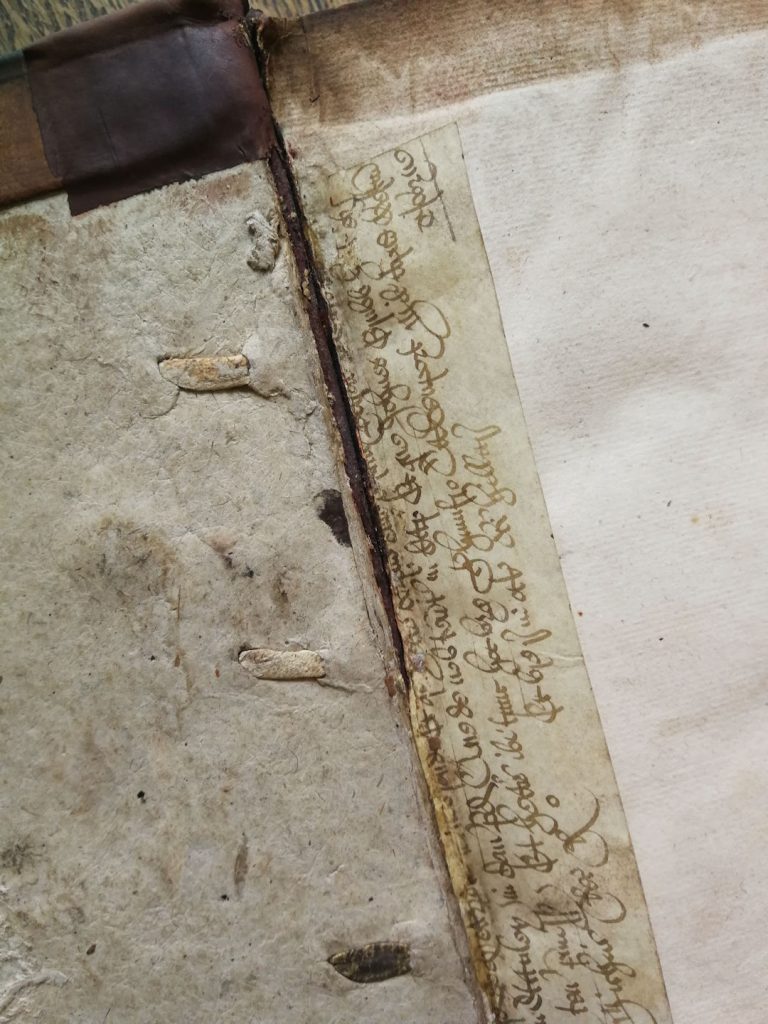

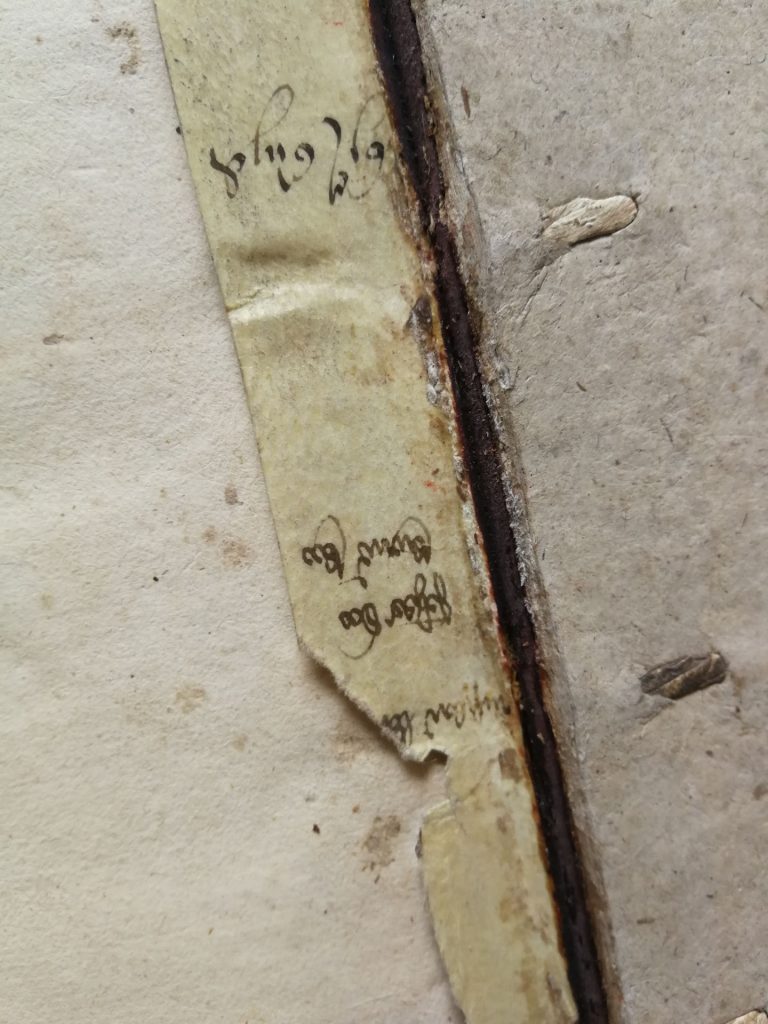

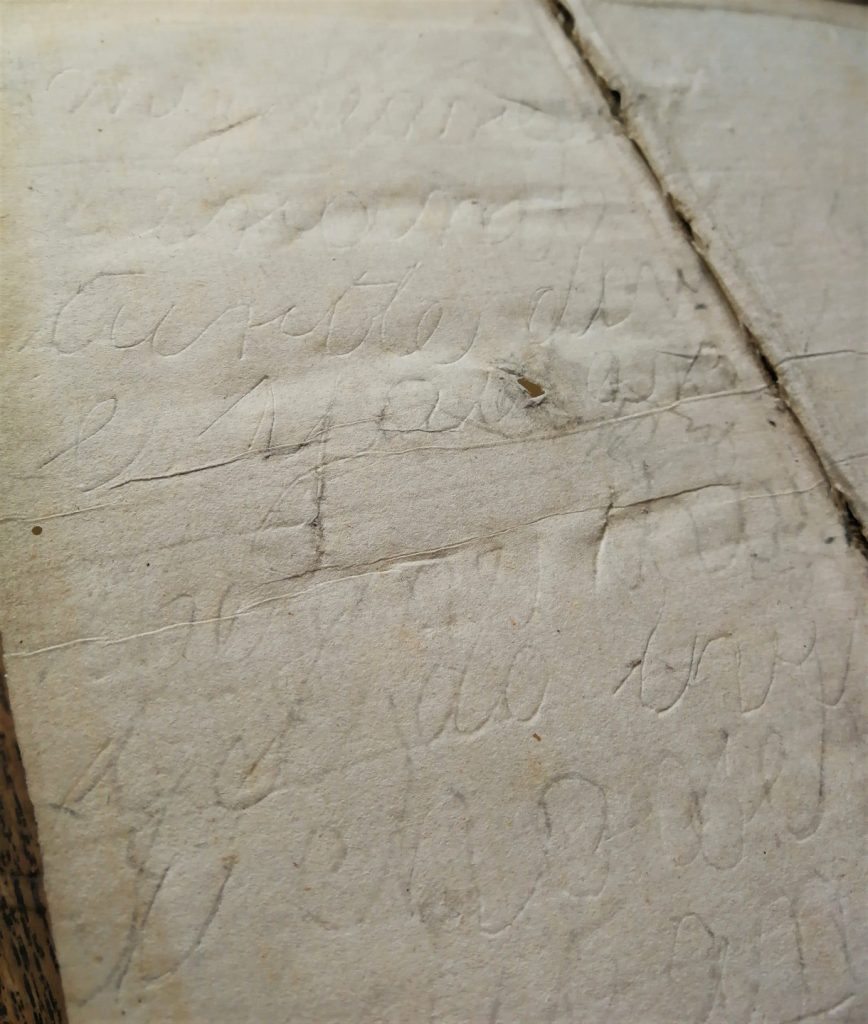

The illustration preserved upside-down on the spine of this book shows Mr. Weller, first seen in Charles Dickens’s The Pickwick Papers. This illustration actually comes from Dickens’s short-lived periodical, Master Humphrey’s Clock which featured some Pickwick Papers characters in its short stories, which framed instalments of the serialised novels Barnaby Rudge and The Old Curiosity Shop. Dickens himself cancelled the periodical in 1841, in favour of releasing writings on a monthly basis rather than in the weekly paper.

The rest of the illustration is hidden by the binding, but the image to the right shows what the full picture looked like, and the text it went with can be read here.