1905-1996

Merze Tate

Professor Merze Tate’s life is full of firsts, breaking racial and gender barriers in pursuit of education. She was the first African-American woman to study at Oxford University and the first African American to be awarded a B.Litt. by the university in 1935. A specialist in international and diplomatic history, she counselled General Eisenhower on disarmament in the late 1940s. She attended The Society of Oxford Home-Students (now St Anne’s College) from 1932 to 1935.

Image, right: Merze Tate at Oxford. Courtesy of the Western Michigan University Archives and Regional History Collections

Education and Early Life

Merze Tate was born in 1905 in rural Western Michigan to a family of African-American settlers. From the start, she displayed remarkable academic talent, despite having to walk four miles to and from school every day. Unfortunately, her high school was destroyed in a fire before she could graduate, leading to an early graduation decision for the students. Event though she was the youngest and the only African American in her class, Merze was selected as the valedictorian at the end of the tenth grade.

However, due to not completing her final years of high school, Merze did not meet the necessary requirements for college admission. Undeterred, she left home and worked as a maid to support her studies at Battle Creek High School, where she maintained an impeccable straight-A record. Merze’s passion for history and social sciences was evident even during her high school days.

When I entered college, I knew exactly what course I wished to pursue.

(Merze Tate, in her student file, St Anne’s College Archives)

Merze received a scholarship to Western State Teachers College (now Western Michigan University) and became the first African American to graduate, earning a teaching diploma and a bachelor’s degree with honors in 1927.

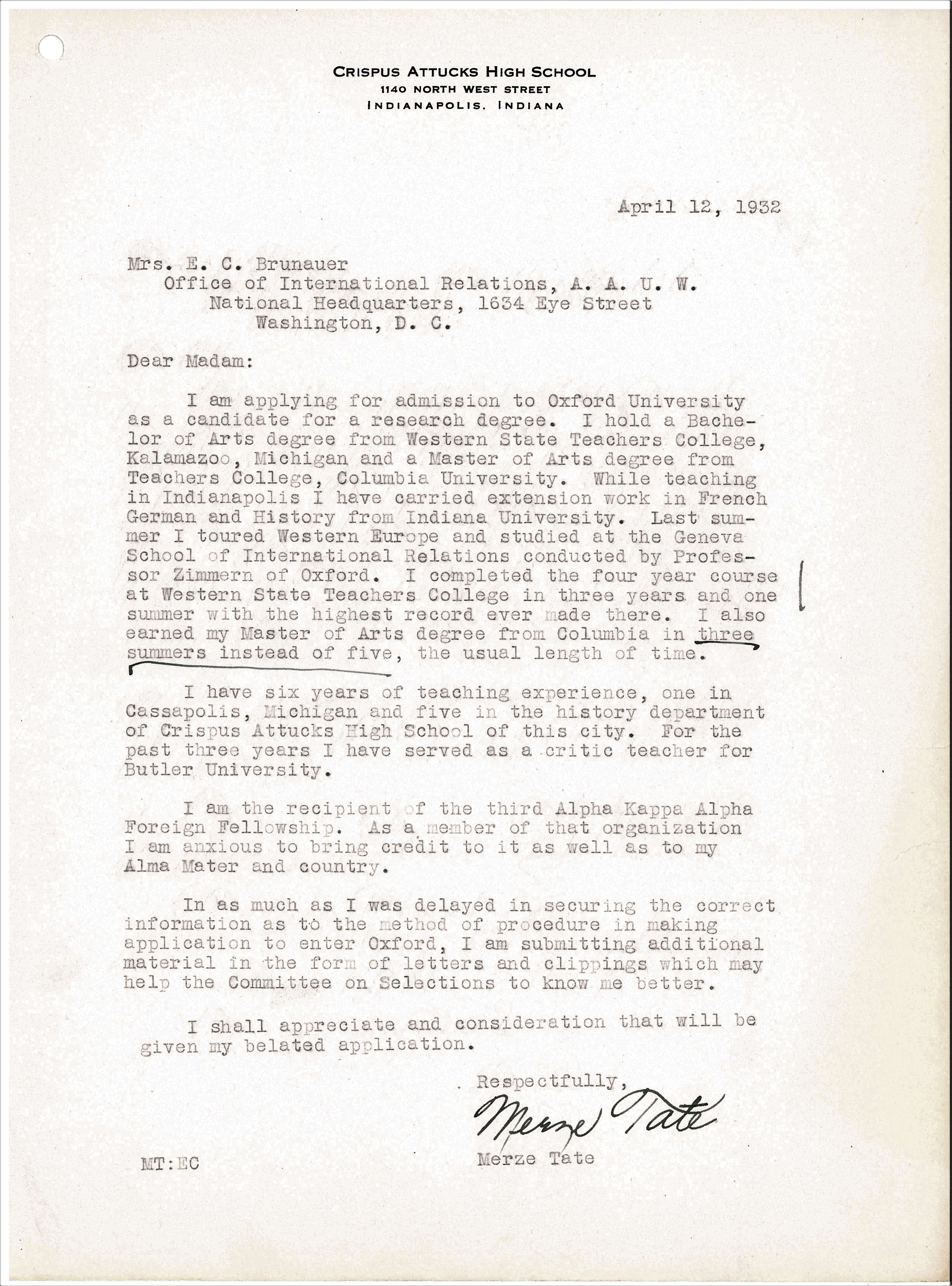

Once again, Merze faced a significant barrier as she was prohibited from teaching high school in Michigan due to her race. Determined to pursue higher education, she relocated to teach history at Crispus Attucks High School, situated in a predominantly black neighborhood in Indianapolis. While teaching, Merze attended Indiana University Extension Classes and pursued a part-time Master’s degree at Columbia University. During the summers, she also attended Professor Zimmern’s Geneva School of International Relations, who would later offer guidance on her B.Litt thesis at Oxford.

Merze’s student file in the college archives contains numerous copies of her applications and highlights her outstanding academic achievements. Her dedication to learning and her impressive academic record are evident throughout her educational journey.

Coming to Oxford

With an Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority scholarship (the first intercollegiate historically African American sorority), Tate applied to the Society of Home Students (now St Anne’s College) to pursue a B.Litt. in International Relations. This demonstrates Tate’s remarkable ambition and determination to pursue her goals. However, she faced numerous challenges along the way.

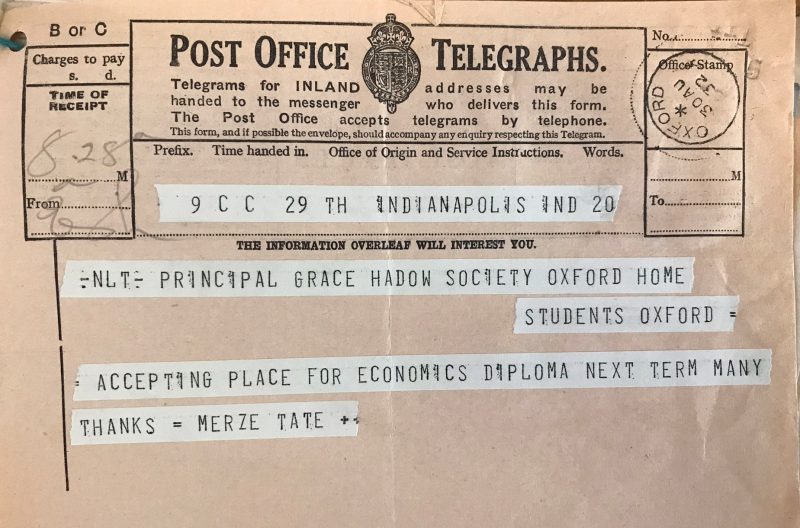

First, she had to pass the screening at the American Association of University Women, an organization that, at the time, did not admit black women as members. Overcoming this discriminatory barrier, she proceeded to battle concerns from The Society of Oxford Home-Students regarding the level of her previous studies and whether they had adequately prepared her for the rigorous demands of an Oxford research degree. The Society offered her a diploma in economics as an alternative option.

Despite these obstacles, Merze Tate persisted in her pursuit of a B.Litt. degree in International Relations, displaying her unwavering determination and refusal to settle for less. Her application and academic achievements spoke for themselves, showcasing her commitment to her chosen field and her readiness to undertake advanced research at Oxford.

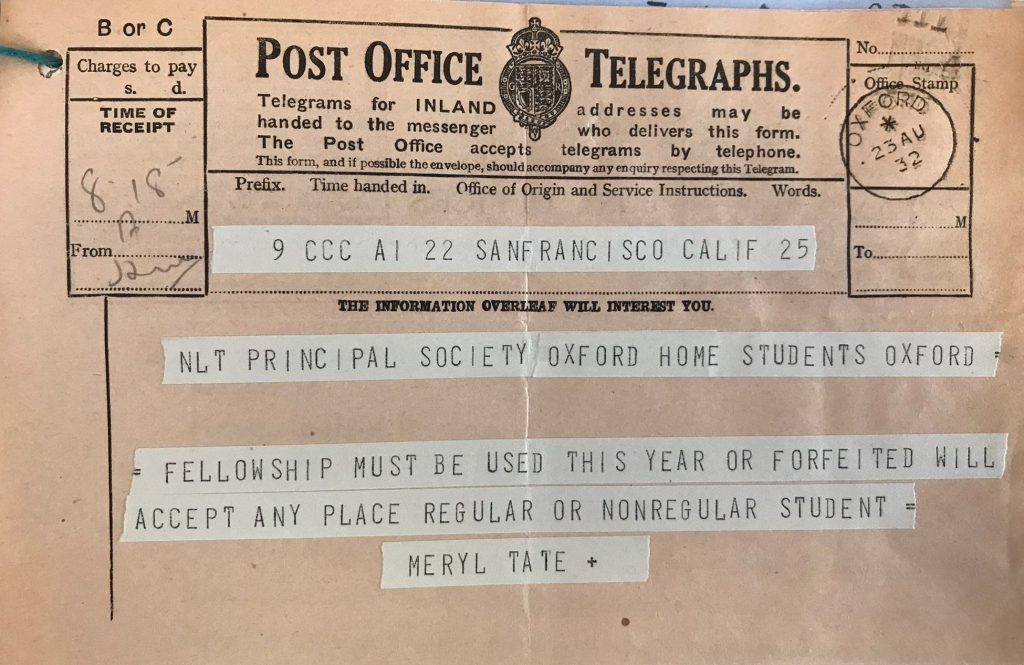

With her scholarship applicable only for that academic year, Tate accepted the offer to pursue the diploma instead, confident in her ability to demonstrate her suitability for the B.Litt. degree. While traveling on the steamer to the UK, she composed a poem expressing her aspirations of studying within Oxford’s “ancient walls, Covered with ivy, hiding famous halls,” at the university she regarded as the “mother of learning.” Her heartfelt verse revealed her one great desire: to be a “credit to my race and sorority.”

Merze Tate’s poem reflects her deep sense of purpose and determination to excel academically while also carrying the weight of representing her community and sorority with distinction. It encapsulates her aspirations to break barriers, succeed against all odds, and leave a lasting impact on the world around her.

Thoughts on Entering Oxford

A sonnet written by Merze Tate on the steamer to Southampton

When I consider what before me lies,

A chance to make a name, A chance to die,

A chance to gather from these ancient walls

Covered with ivy, hiding famous halls.

What this mother of learning is ready to bestow

On one who has the courage to go

Through endless hours of toil and grief and joy.

I think of constant strife without these walls

And wonder if our lives are worth the while

We spend on earth nurturing petty whiles

Then I recall: ‘Who best bear his yoke

May serve Him best’

This relieves my mind and then I rest.

And make my one big wish a prayer to be

A credit to my race and my sorority.

(from Barbara D. Savage, Professor Merze Tate: Diplomatic Historian, Cosmopolitan Woman)

Overcoming Hardships

In 1932, Merze Tate arrived in Oxford and matriculated as a member of The Society of Oxford Home-Students (now St Anne’s College), becoming the first African-American woman to be a member of Oxford University. Initially, she was admitted to pursue the Diploma in Economics and Political Science, which was a one- or two-year course that did not grant a degree on its own.

However, through her diligence and strong determination, Tate was able to convince the college to allow her to switch from the Diploma course to the B.Litt. Degree. The B.Litt. degree was a research-focused program that typically spanned two to four years, during which students conducted independent study under the supervision of an advisor. It is worth noting that the B.Litt. degree did not necessarily involve formal tuition but required extensive research and academic work.

There is little mention of Tate’s race in her student files. Former St Anne’s College Librarian David Smith comments that ‘to the Misses Butler, Miss Hadow and their contemporaries, to have done so would doubtless have been both bad manners and a distraction from that generation’s rigorous and steely pursuit of learning’ (The Ship, 2010). However, it is important to recognize the broader context and the additional hurdles Tate would have likely faced as a trailblazing African-American woman in an academic setting that was predominantly white and male.Tate would have been one of a very small number of women in Oxford in the 1930s, and with degrees not granted to women until 1920, we might imagine she faced considerable difficulties as a female graduate, as well as racial prejudice.

Professor Barbara D. Savage of University of Pennsylvania delivered the Astor Lecture at Oxford University on Merze Tate in 2016. She has drawn on the travel diary of Tate to explain the influence of international ideas on Tate’s work:

Whatever trepidations Tate had about her decision dissipated quickly. She found Oxford to be “a dream of a place” with its richness of history; she reveled in its intellectual, cultural, and social offerings. She enjoyed its traditions and joined in many of them, including learning to ride a bicycle for the first time, replete in her academic gown and hat. Being there shaped her sense of herself as a scholar and confirmed for her that she could compete well with white men in classes and on examinations. But she also remained very aware of the singularity of her status there as a woman of color engaged in graduate level work: “I was the only colored American in the entire university, man or woman, and the first to get a higher research degree.” For the rest of her life, she would proudly remind people that although Alain Locke in 1907 had become the first African American Rhodes Scholar, he was a mere undergraduate at Oxford while she had been awarded her degree for graduate work.

(from Professor Merze Tate: Diplomatic Historian, Cosmopolitan Woman)

Despite her scholarship only covering one year, she had sold her house and saved money to fund her studies. However, a financial crisis in the United States cut off her access to her funds, leaving her in a precarious situation. She had to seek loans to sustain herself and continue pursuing her degree at Oxford. The correspondence in her student file reflects the pressure and uncertainty she faced due to financial insecurity. Numerous applications and reference requests for scholarships and loans from hardship funds are documented in her file.

While working on her research, Merze Tate resided in North Oxford and spent her summers as a tutor in France. She also attended summer courses at the Geneva School of International Studies in Switzerland and the University of Berlin in Germany.

Her tutors, as noted in her file, commented on Tate’s ‘keenness and industry, so much so that she accumulated too much material’ (Reference from Miss Butler, 3 July 1935). After 9 months work, she was advised to confine her subject to a shorter period and her thesis was further delayed by revision. However, her journey was fraught with additional challenges. Just before she was set to submit her thesis, Merze suffered an injury that required her to leave Oxford for recovery. The documents in her file reveal a tense situation, with urgent communication between her principal and examiners regarding her ability to complete her degree.

Dashed notes in her file describe a dramatic turn of events. Merze Tate initially sends a last-minute note stating that she had an accident and couldn’t submit her thesis. The Principal urgently contacts her examiners, only for her tutor to later note that Merze had arrived, injured but able to submit her thesis. The outcome of her degree remains uncertain at this point in the file, leaving readers in suspense as to whether she will succeed or fail in her pursuit of the degree.

It is impossible not to become invested in Tate’s journey and to be impressed with her confidence and undoubtedly high work ethic.

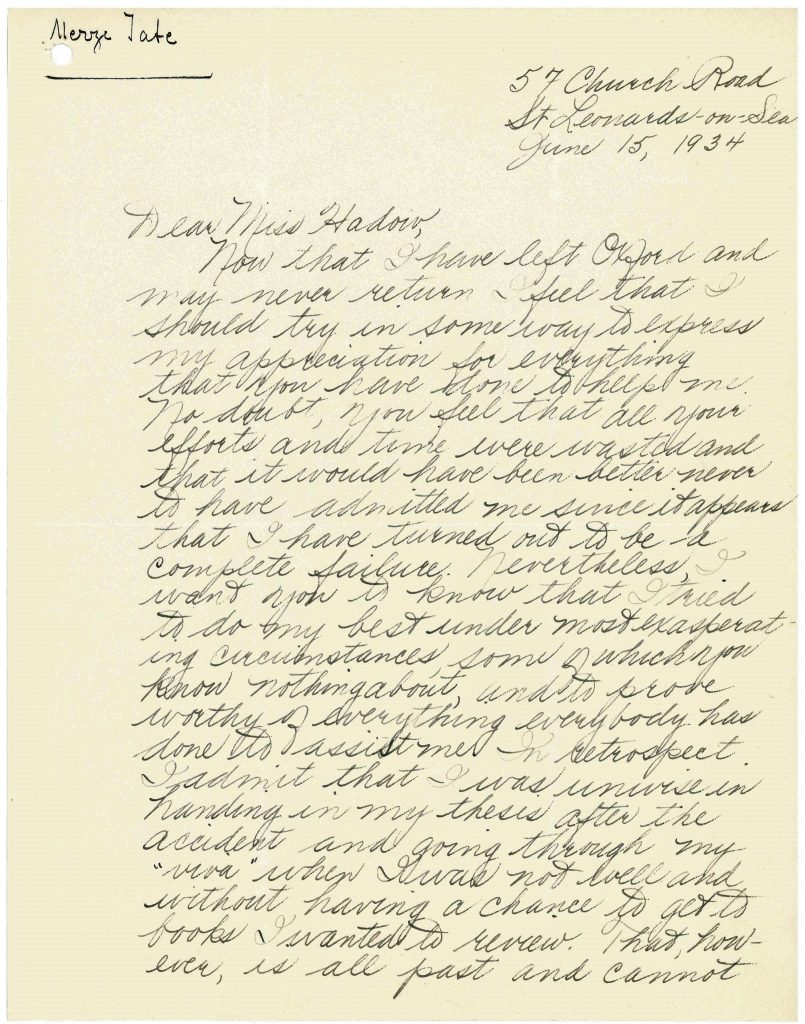

Correspondence between Merze Tate and Grace Hadow, the principal of the Society of Oxford Home Students, reveals an issue with her thesis submission.

Merze Tate submitted her thesis titled ‘The Movement For Disarmament 1853-1914’ in May 1934 and underwent her viva voce examination on 26 May. However, on 12 June, the Examination Board reported that they had not reached a decision and recommended that she resubmit her thesis the following year. To be awarded an Oxford degree, it was necessary to provide evidence of residence at Oxford during term time. Merze Tate realized that the financial burden of staying in Oxford for another year would be too much for her to bear.

A poignant and deeply affecting letter from Merze Tate to Miss Hadow, written shortly after receiving the news from the examiners, further illuminates the emotional impact of the situation. The contents of this letter likely express her disappointment, frustration, and the heavy weight of the circumstances she found herself in.

Now that I have left Oxford and may never return I feel that I should try in some way to express my appreciation for everything that you have done to help me. No doubt, you feel that all your effort and time were wasted and that it would have been better never to have admitted me since it appears that I have turned out to be a complete failure. Nevertheless, I want you to know that I tried to do my best under most exasperating circumstances, some of which you know nothing about, and to prove worthy of everything everybody has done to assist me.

(Letter from Merze Tate to Grace Hadow, 15 June 1934)

'I have failed'

Reading the letter: it is clear that Tate is deeply distressed and is in despair after all her hard work. This is the first of the many, many obstacles that she has encountered in her academic career which she has been unable to overcome. Tate describes it as ‘the first great failure of my life’. In her correspondence with Grade Hadow, she further expresses:

The great pity is that in the final analysis – and in simple language – I have failed. What I now want to ask is, of course, too much to expect, but nevertheless, it would not be fair to others if I remained silent. I do hope that you will try to forget that I was ever a Home Student and that I ever existed. I beg this of you because I do not want you to use me as a standard for judging others of my race. I know this is too much to ask for most members of your race judge the members of the coloured race by one or two whom they have known, instead of each person individually.

But I consider you so far superior to most people that I dare to hope you may be a little wiser in this respect. If ever another young coloured woman should apply to come up to Oxford I hope that you will judge her on her own merit and not think of me and all the trouble I caused. There are hundreds of coloured women in America who would come up to Oxford and be successful for they would have money enough to live free from financial worries and brains sufficient for them to pass any examination. Please remember this when you are considering future candidates. It is most unfortunate that I as a pioneer had to face so many difficulties and then not succeed. It is the first great failure of my life but I am anxious that others should not suffer because of my failure. (Letter from Merze Tate to Grace Hadow, 15 June 1934)

Six months after the Examination Board convened in June 1934, Merze Tate received notification that she had not succeeded. The official reasons for her failure were never provided (as noted by Miss Butler in a handwritten comment on Tate’s letter on 20 June 1935). However, she was readmitted to the University on 1 December 1934, with an altered and condensed subject titled ‘Public Opinion And The Movement For Disarmament 1888-1898,’ which she submitted the following May. This time, she achieved success. In total, Merze Tate spent three years at Oxford. She secured funding through scholarships and hardship funds, which she later repaid, to resubmit her thesis. In 1935, she was awarded her B.Litt. degree.

Keeping in touch and beyond Oxford

Tate’s student file reveals that she maintained communication with her former tutors, sending letters and postcards from her travels. In 1936, she contributed to the funding for Hartland House, the first building of the College, which now houses the library. In recognition of her accomplishments, Group Study Room 1 in the Tim Gardam Building, completed in 2017, was named in her honour.

Throughout her career in Oxford, Miss Tate showed herself a keen student and one possessing energy and determination. Her conduct was uniformly excellent […] I am quite sure that she is not easily daunted by difficulties and that she would show courage and initiative where such qualities were needed. Her personal integrity is beyond reproach, and she has a keen sense of honour.

(from a letter of recommendation from her Oxford tutors for a teaching position following her studies)

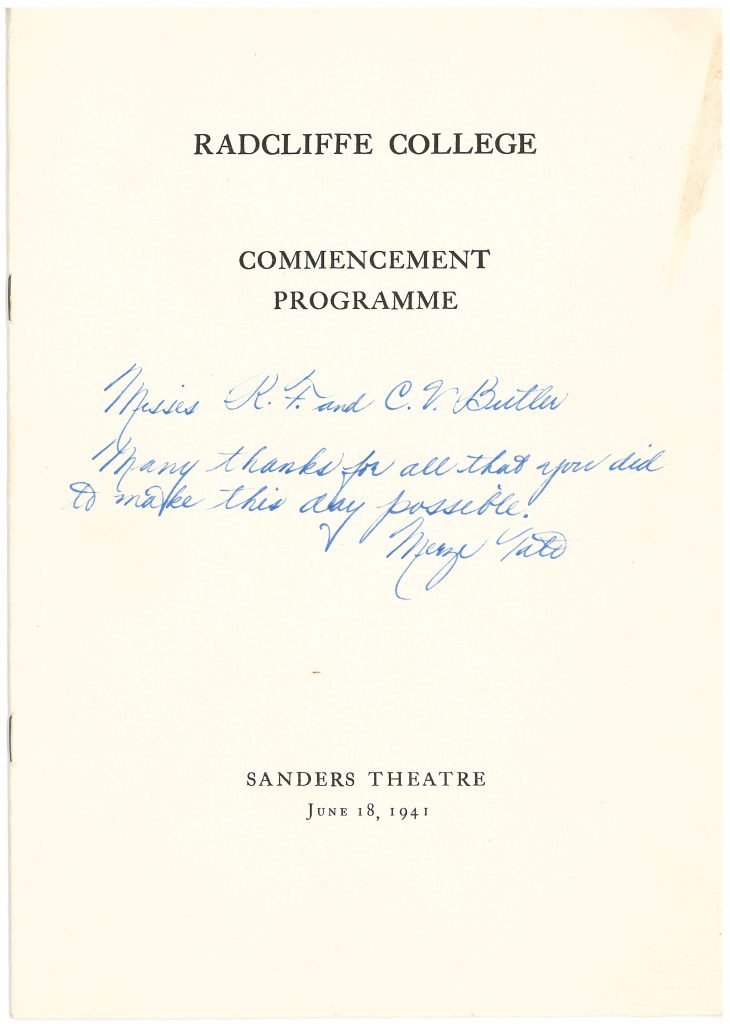

Merze Tate went on to become the first African-American woman to earn a doctorate in Government and International Relations from Harvard University’s Radcliffe College in 1941. She expressed her gratitude for the support of her former tutors by sending them a copy of the commencement program, with the inscription “May thanks for all that you did to make this day possible.” On the programme, she also proudly noted ‘Inducted Into Phi Beta Kappa June 17’. She later published her dissertation, titled ‘The Movement for a Limitation of Armament to 1907’, which she gifted to St Anne’s College Library, where it can now be found in the St Anne’s Authors collection.

Merze Tate’s legacy includes her contributions to challenging gender and racial discrimination within the academic system. In 1942, she became the first Black female professor of history at Howard University, a position she held for 35 years. Her books encompass studies on the disarmament movement and the relations between Hawaii and the United States.

Awareness of Merze Tate and her remarkable work has been increasing, resulting in numerous new publications that delve into her life and achievements. These resources provide further insight into her significant contributions and serve to commemorate her enduring legacy (please see Further Reading and Sources below for further information).

Further Reading and Sources

Images and text from letters, reports, and records from St Anne’s College Library and Archives.

Books by and about Merze Tate in St Anne’s College Library

- Tate, Merze. The Disarmament Illusion: The Movement for a Limitation of Armaments to 1907. Bureau of International Research, Harvard University and Radcliffe College. New York, 1942. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990199485620107026)

- National Emergency Council. Report on Economic Conditions of the South. Washington: [U.S. Govt. Print. Off.], 1938. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990126624110107026)

- Hollins, Sonya and Sean, Small Beginnings: A Photographic Journey Through the Life of Merze Tate (2018)

- Savage, Barbara D., Merze Tate: the global odyssey of a Black woman scholar . Yale University press. New Haven ; London, 2023. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/k30gf0/alma991025488836207026)

- Smith, David, ‘From the Librarian: The Lives of Others.’ In The Ship. Oxford: St. Anne’s College. Assoc. of Senior Members, 2010-11: 5-6. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990123740420107026)

- Vitalis, Robert. White World Order, Black Power Politics: The Birth of American International Relations. United States in the World. Ithaca, 2015. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990205460010107026)

Further Reading

- Beilke, Jayne R. “Tate, Merze.” – Oxford African American Studies Center. 31 May. 2013; Accessed 1 Mar. 2023. (https://doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.37990)

- Black Women Oral History Project Interviews, 1976–1981 (https://guides.library.harvard.edu/schlesinger_bwohp)

- Harris, Joseph E. “PROFESSOR MERZE TATE (1905-1996): A Profile.” – Negro History Bulletin 61, no. 3/4 (1998): 77–93. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44177057

- “Merze Tate.” in Women’s International Thought: Towards a New Canon, edited by Patricia Owens, Katharina Rietzler, Kimberly Hutchings, and Sarah C. Dunstan, 49-54. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022. (https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009004978)

- Savage, Barbara D. “Beyond Illusions: Imperialism, Race, and Technology in Merze Tate’s International Thought.” in Women’s International Thought: A New History, edited by Patricia Owens and Katharina Rietzler, 266-85. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021. (https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108859684.017)

- Perkins, Linda M. “Merze Tate and the Quest for Gender Equity at Howard University: 1942–1977.” in History of Education Quarterly 54, no. 4 (2014): 516-51. (https://doi.org/10.1111/hoeq.12081)

- Savage, Barbara D., “Professor Merze Tate: Diplomatic Historian, Cosmopolitan Woman.” in Toward an Intellectual History of Black Women (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 252–270. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990205972230107026)

- Selby, Gil, ‘Professor Barbara Savage, Professor Merze Tate, and Black Women’s Intellectual History’, –TORCH (18 Feb 2016) (Accessed at: https://www.torch.ox.ac.uk/article/professor-barbara-savage-professor-merze-tate-and-black-womens-intellectual-history)

- Women in Oxford’s History Podcast, ‘Series 2: Merze Tate (1905-1996)’. (Accessed at: https://womenofoxford.wordpress.com/2017/10/31/merze-tate/)

- Woodard, Maurice C. ‘Merze Tate.’ in PS: Political Science & Politics 38, no. 1 (2005): 101-02. (https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096505055885)

This article was written by Elizabeth Dawson, Library Assistant.