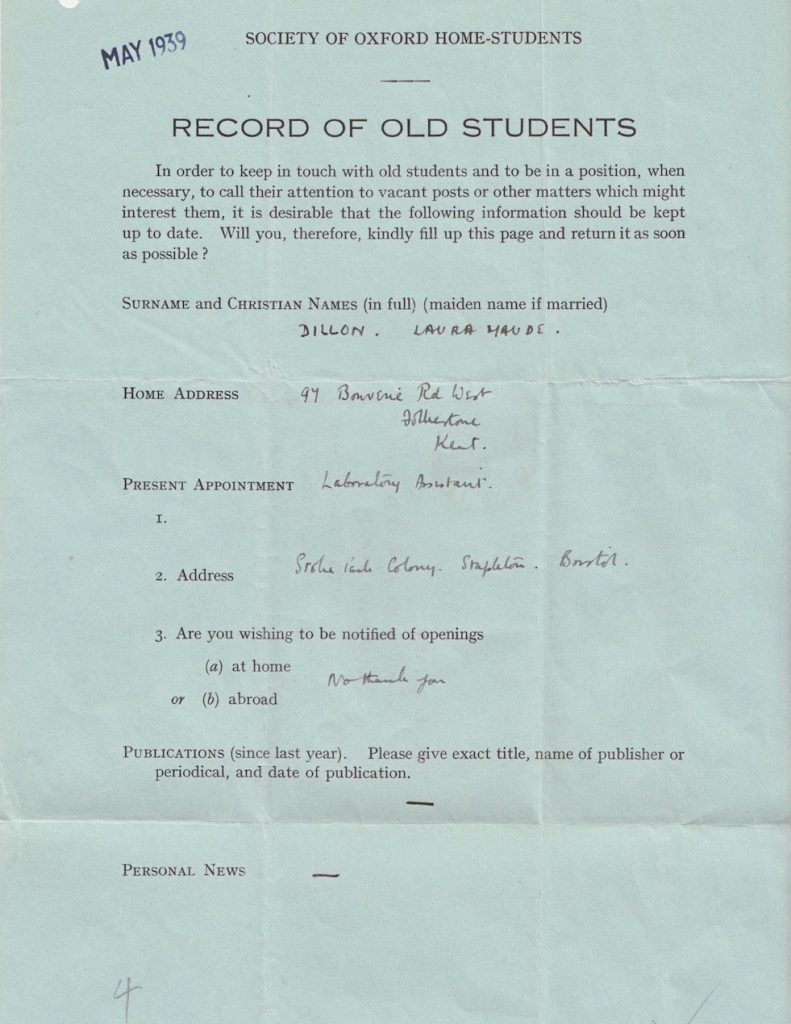

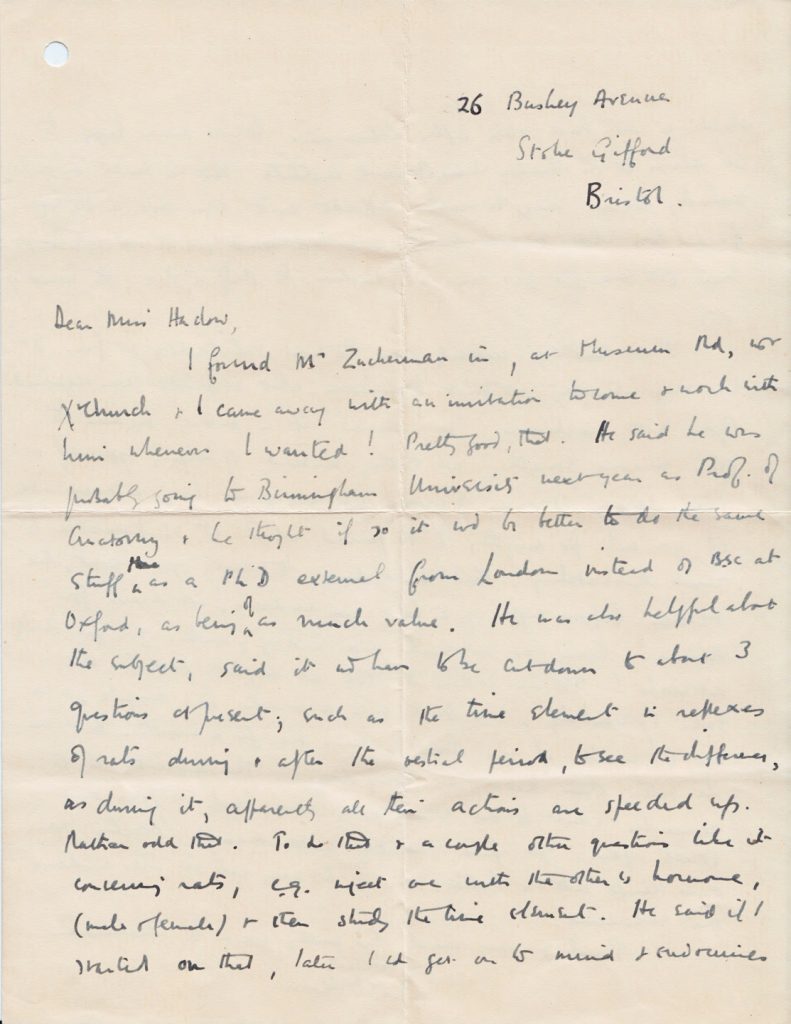

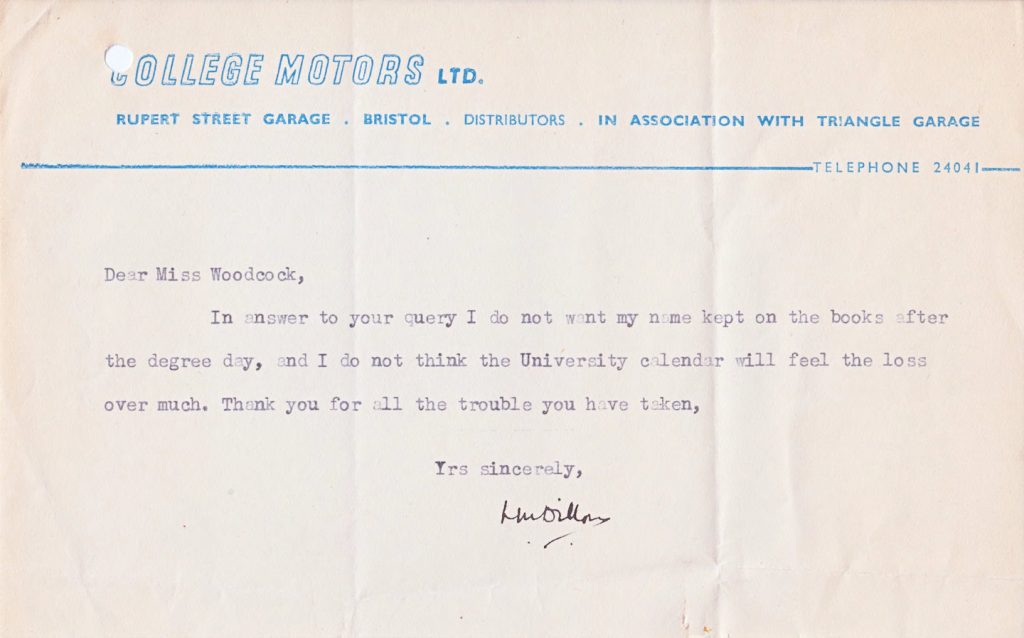

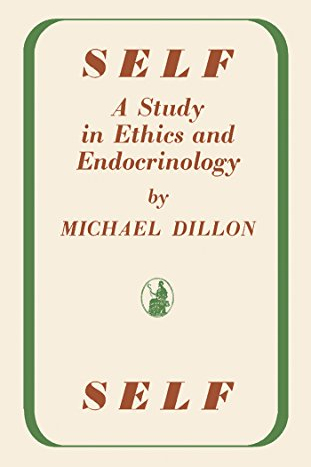

Childhood

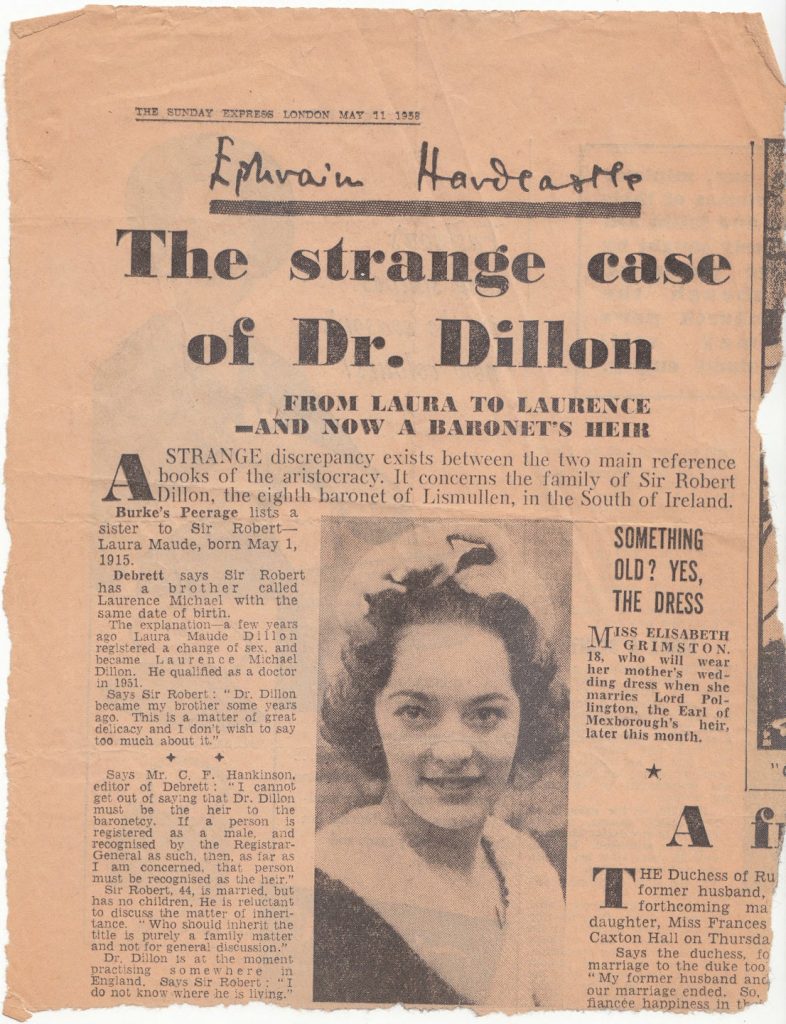

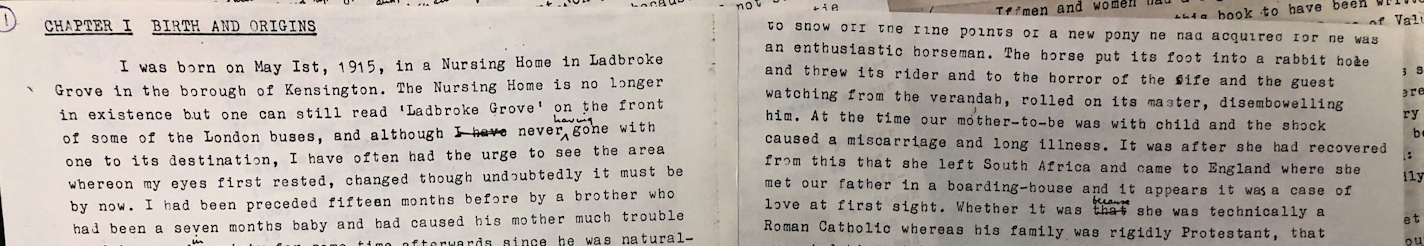

Born Laura Maud in 1915, Dillon grew up in Folkestone with his aunts. His mother died of sepsis just days after his birth and his father of alcoholism ten years later. Despite this and the state of semi poverty enforced by the frugality of their aunts, Dillon and his brother Bobby had a fairly untroubled childhood and holidayed on the family land in Ireland each summer. Yet as the years went by, he felt a growing unease at the different way he and his brother were treated:

I was out for a walk with the eighteen year old nephew of the Vicar […] and somewhere there was a gate which he opened and stood aside to let me pass through first. Suddenly I was struck with an awful thought, for no one had done this for me before. “He thinks I’m a woman.” It was a horrible moment and I felt stunned. I had never thought of myself as such despite being technically a girl.

–p.73, Out of the Ordinary

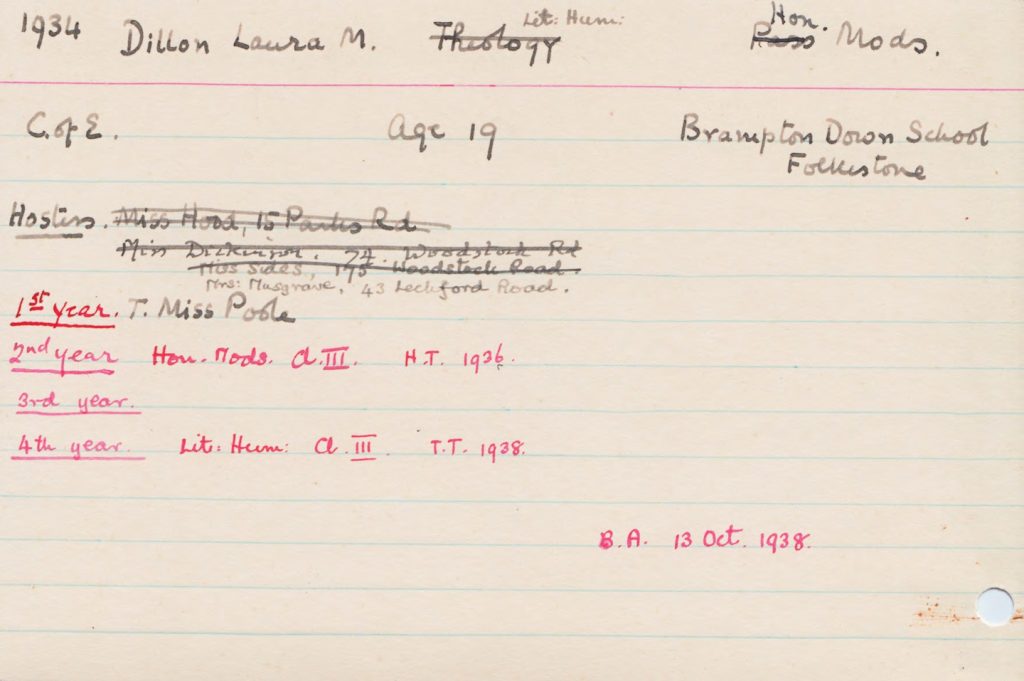

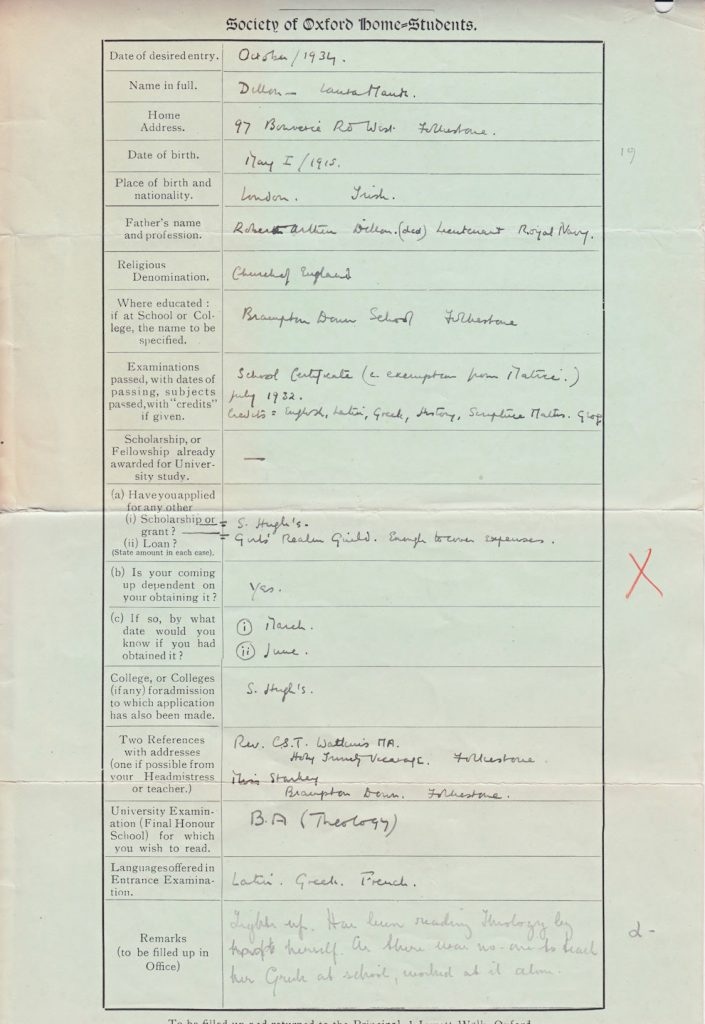

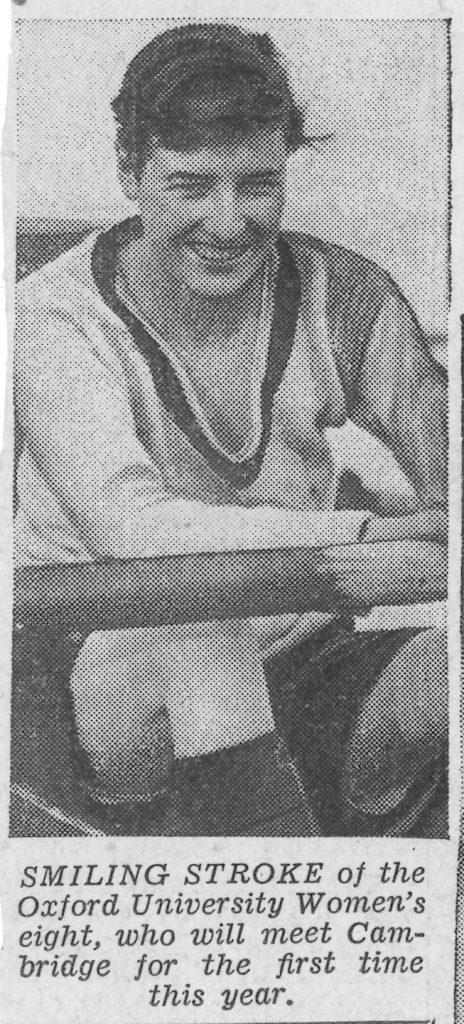

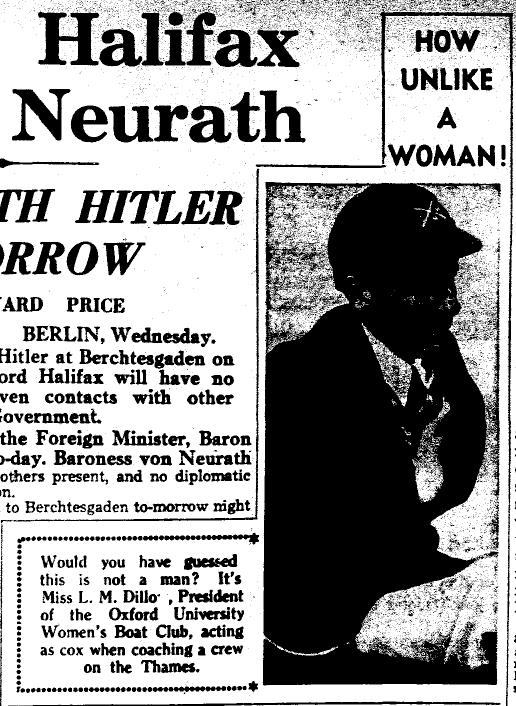

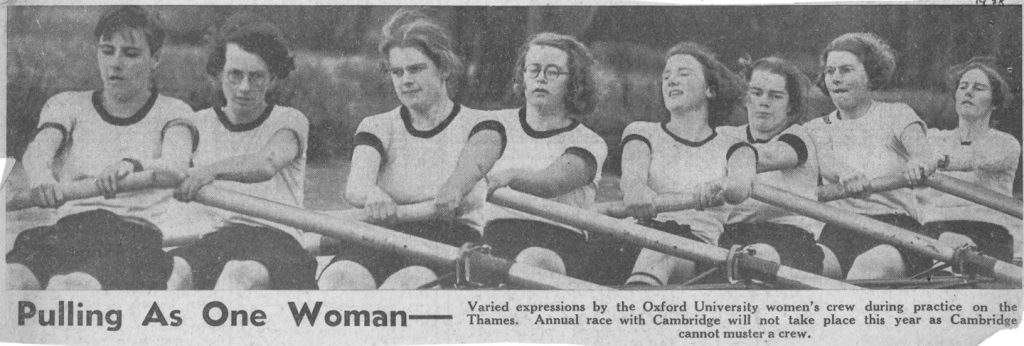

Applying to Oxford was a way to escape, or at least delay, the inevitabilities of life as a woman. The vicar supported the contemplative yet determined Dillon in applying to read Theology at The Society of Oxford Home-Students (as St Anne’s was then known) where he won a place and entered in 1934 for a pass degree. The same wilfulness led him to persuade his tutors of a change to Classics within the year.

![A love poem from Dillon to Roberta [Private collection of Liz Hodgkinson]](https://www.st-annes.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Undated_52_Poem_LHC.jpg)

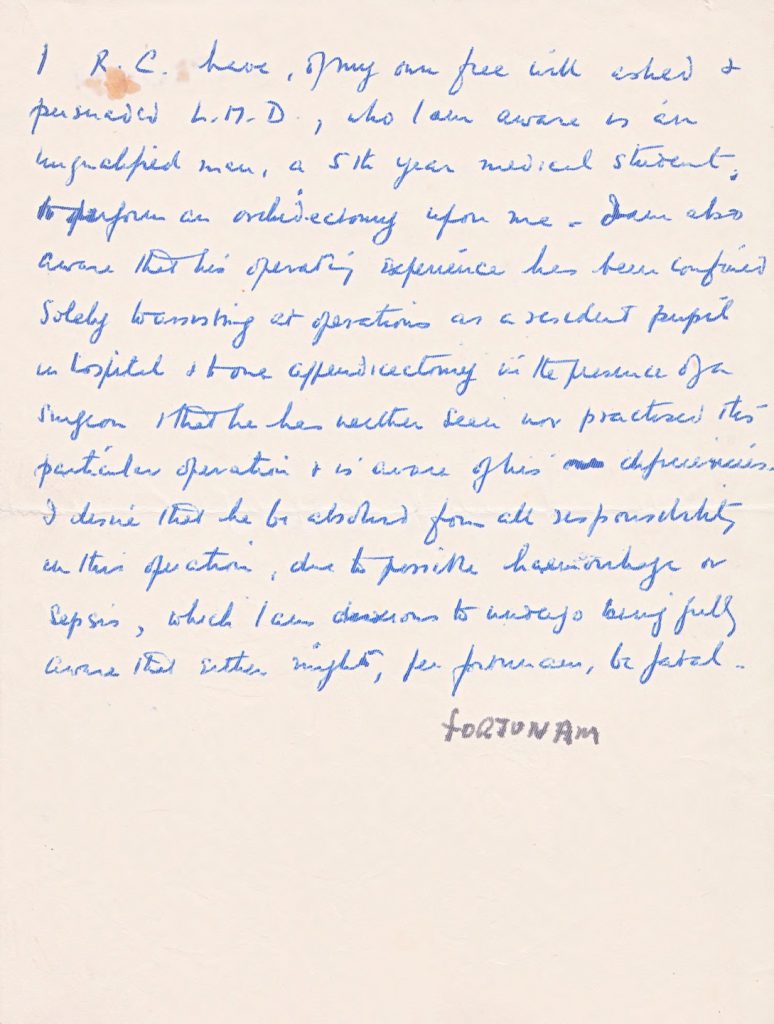

![Dillon's first letter to Cowell [Private collection of Liz Hodgkinson]](https://www.st-annes.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Undated_17_LHC_ForDisplay_1.jpg)

![Dillon's first letter to Cowell [Private collection of Liz Hodgkinson]](https://www.st-annes.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Undated_17_LHC_ForDisplay_2.jpg)

![A romantically signed letter [Private collection of Liz Hodgkinson]](https://www.st-annes.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Undated_43_LHC_ForDisplay_1.jpg)

![A romantically signed letter [Private collection of Liz Hodgkinson]](https://www.st-annes.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Undated_43_LHC_ForDisplay_2.jpg)