This article is part of a series.

For the beginning of this series, read our first article: The Early Years.

A Growing College

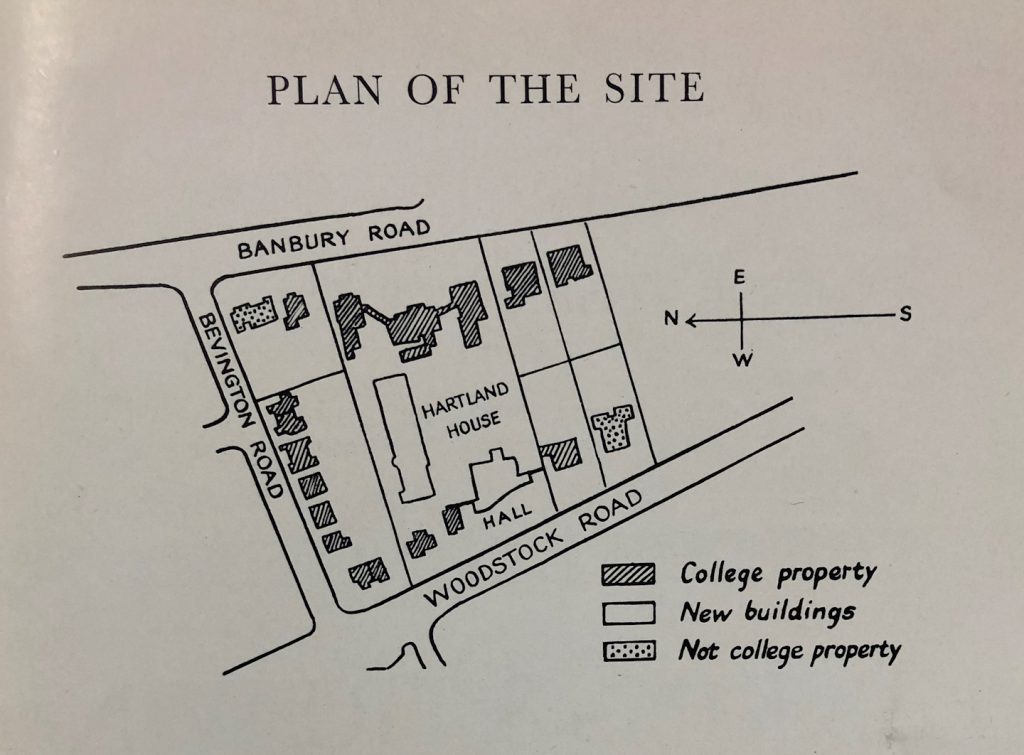

For twenty years after its construction, Hartland House remained the only purpose-built collegiate structure on the Woodstock Road site. In line with Giles Gilbert Scott’s initial design, it had been expanded and a second module opened in 1952. When Mary Ogilvie was appointed Principal in 1953, it sat among the gardens of large houses that were gradually acquired by the College over the next ten years.

In 1959, a dining hall was completed on Woodstock Road. With Hartland House to the North and the linked buildings of Springfield St Mary (run as a hostel for students) to the East, there was the beginnings of a quad forming around the open space of Hartland lawn.

In the late 1950s, the University lifted limits imposed on numbers of women undergraduates. St Anne’s was therefore allowed to expand its student numbers but the Principal was clear that any new students must have a guarantee of accommodation; something which she saw as an essential standard. Although some students lived in Springfield St Mary and others in the newly acquired houses on site, there were still many more scattered around North Oxford and at Cherwell Edge (now Linacre College). Some houses that the College had bought the freehold of still had long term occupants and it would be some years before they could all be used by students and tutors.

Ambitious Plans

The Principal was a tireless advocate for the College and formed a friendly relationship with Sir Isaac Wolfson and his wife. They reportedly had a great interest in girls’ education and on 13th June 1960 the Isaac Wolfson Foundation made a grant of £80,000 to the College. Despite having enough capital for just one accommodation building, St Anne’s engaged an architectural firm, Howell Killick Partridge and Amis, to develop an ambitious master-plan for the whole site.

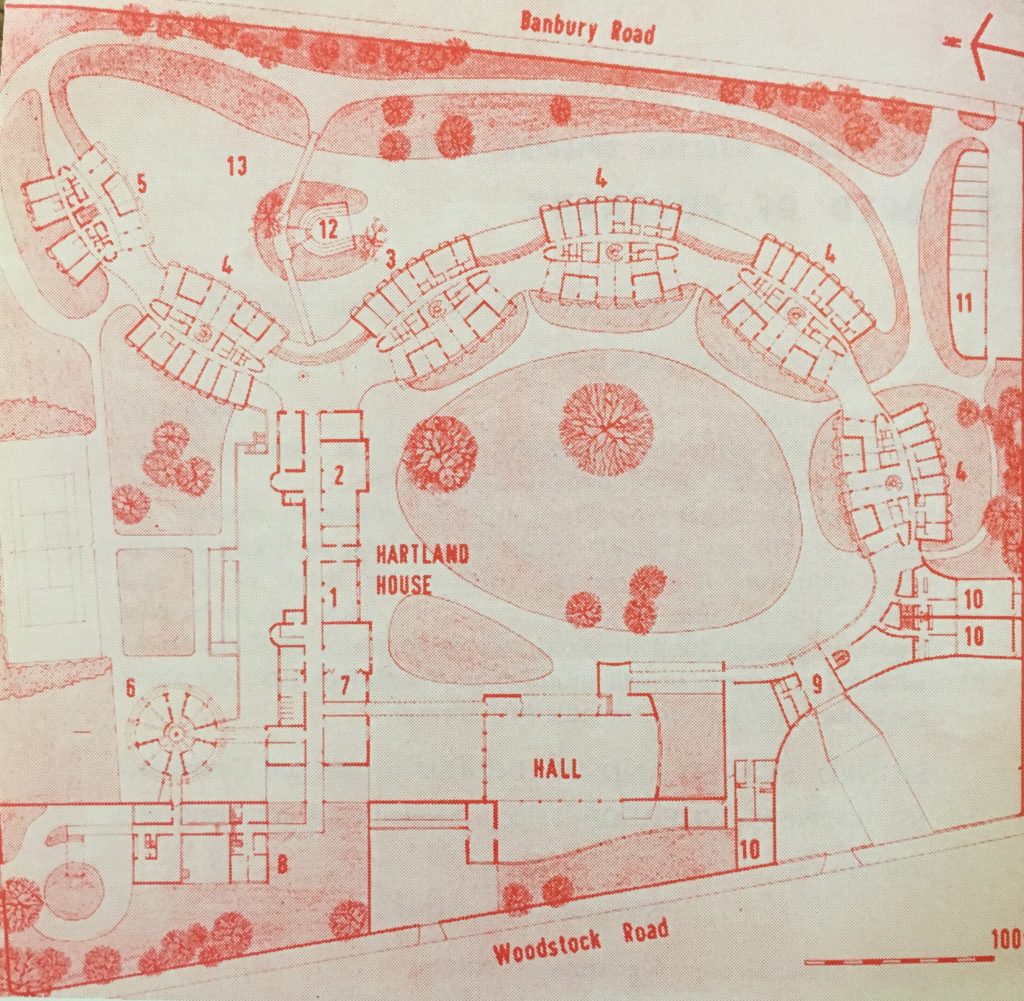

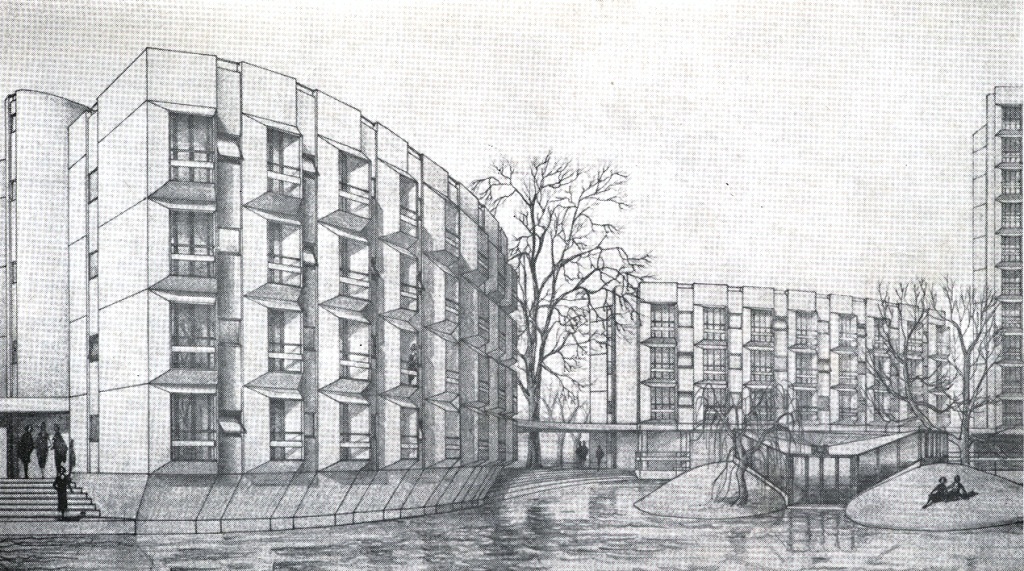

Variously referred to as a ‘string of pearls’, ‘string of beads’ or just ‘the necklace’; the design centered around six large accommodation blocks that would hang like a draped necklace across the Eastern (Banbury Road) side of the College. The largest of these (labelled ‘5’ on the above site plan) was to have been an 11 story tower with views across North Oxford and the University Parks.

Other features included a new Lodge and site entrance to the South West corner on Woodstock Road and a new house for the Principal a little further up. The unified gardens of the Bevington Road houses were in-line to become a tennis court.

Most relevant to this article is a building labelled as ‘6’ on the plan, a new circular library that would have stood just North of Hartland House and connected to it through a first floor walkway.

The circular library, like much of the rest of this master plan, never left the concept phase. As a result we know very little about how it might have been laid out inside, or whether it would have been accompanied by a change in the interior configuration of Hartland House.

A combination of money shortages, lack of confidence in the design and a growing preservation movement meant that plans were drastically scaled back. However anyone with even a passing familiarity with St Anne’s today will recognise the accommodation blocks from the design. Springfield St Mary and one of the adjacent houses on Banbury Road were knocked down to make way for Wolfson (1964) and then later Rayne (1968). As pleasing as it is to imagine the unified vision for the College complete with an artificial lake, there is something to be said for the character of the North Oxford houses that have endured. The concrete brutalism of the ’60s polarizes opinion in the present day.

Straight-forward Solutions

The plans may have been scaled back but the College really did need far more on-site accommodation than it had, and the Library also needed space to expand.

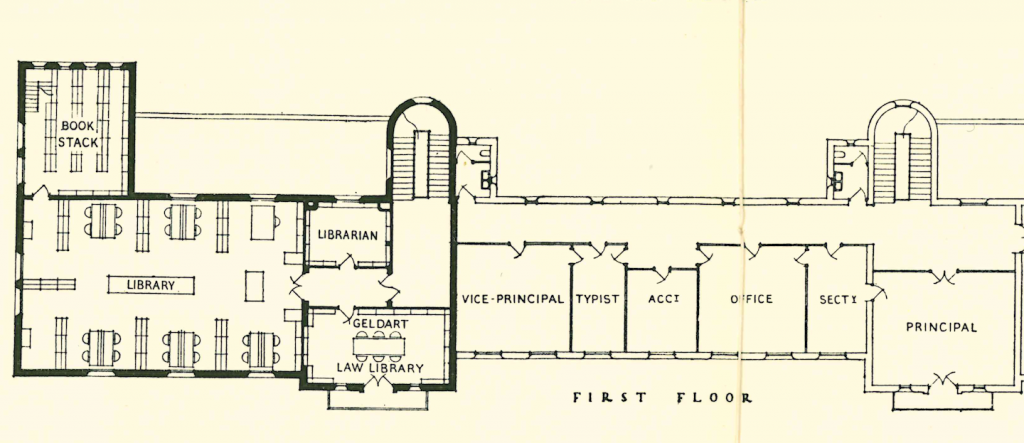

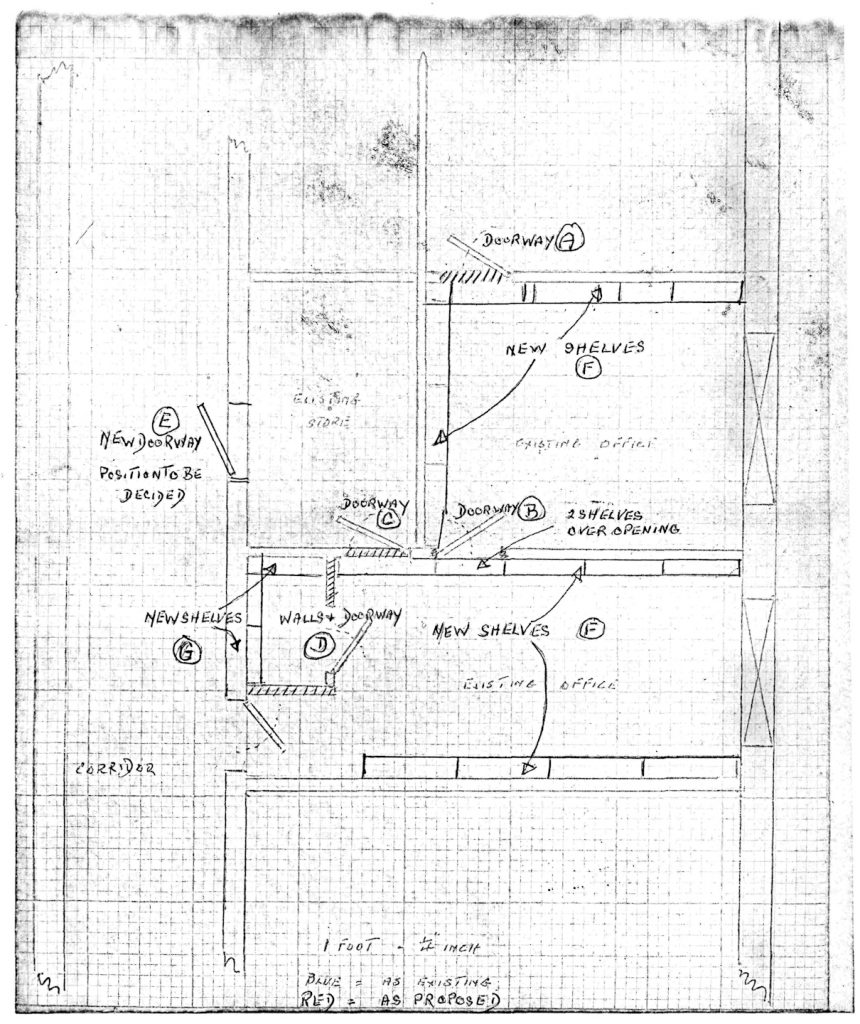

The Library space problem was solved in the most straight-forward way, expanding along the first floor of Hartland House into what had until then been staff offices. Looking at the plan below one can see the original four rooms that have today been subdivided into use for Classics and Modern Languages. A new wall was placed at the end of the corridor before the Secretary to the Principal’s office. A few interior walls were knocked through and doors sealed up to be covered with shelving, but the former layout is certainly still recognisable.

As well as expanded space, the Library also increased its opening hours and became twenty-four hour for the first time in 1967, something which few other Colleges could boast.

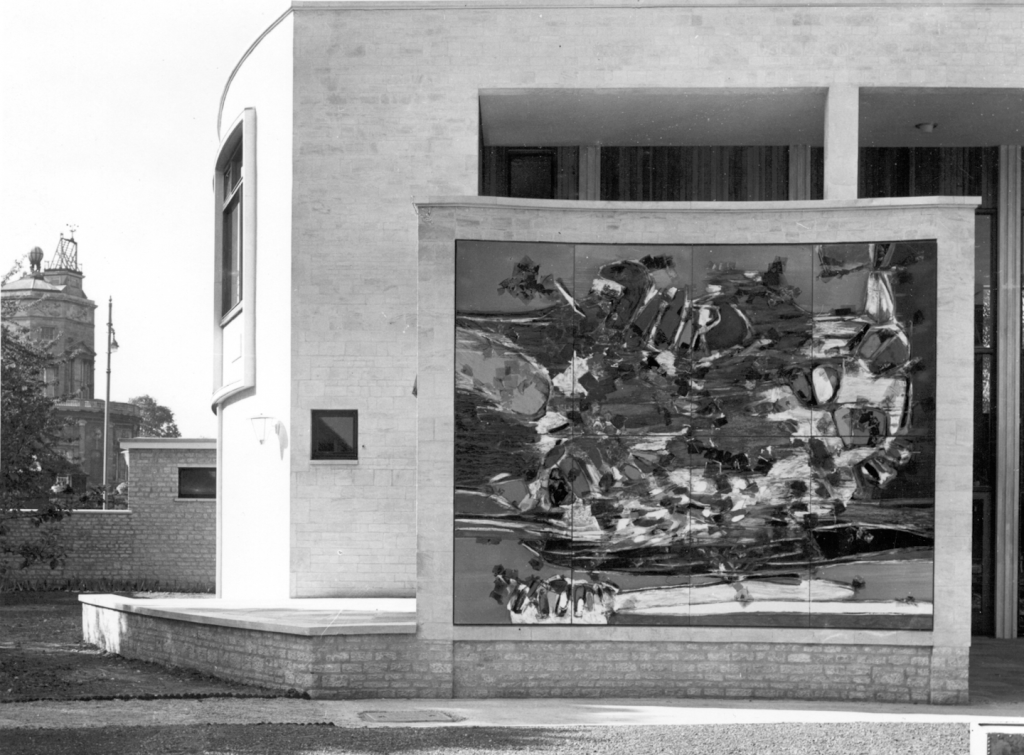

As for accommodation, a third block christened the Founders’ Gatehouse but later known mainly as ‘Gatehouse’ went some way towards alleviating problems as well as providing space for a new Lodge. It was completed in 1966 and paid for by the generosity of senior members and the University Grants Committee. Sitting directly in front of Hartland House, it provided much needed student bedrooms above a gated entrance from Woodstock Road.

Perhaps in an effort to unify the appearance of the College, the Founders’ Gatehouse was of the same brutalist school as Wolfson and Rayne, but on a smaller scale and neatly rounded. Looking again at the model, it is easy to see a resemblance between the planned circular library and the accommodation block that ended up nearby.

Bibliography

- Reeves, M. (1979). St Anne’s College, Oxford : An informal history. Oxford: St Anne’s College. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990123366450107026)

- Smith, D. (2012). St Anne’s College: 1952-2012. Oxford: St Anne’s College. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990193279450107026)

- Society of Oxford Home-Students (1936). Proposed Buildings for the Society of Oxford Home-Students. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990155322550107026)

- Society of Oxford Home-Students (1911-). The Ship. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990123740420107026)

- St Anne’s College Association of Senior Members (1960). St Anne’s College, Oxford : published by the Association of Senior Members to commemorate the visit of Her Majesty The Queen on November 4th 1960. Oxford: St Anne’s College. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990155320860107026)

This article was written and researched by Duncan Jones (Reader Services Librarian).