By 1915, Oxford’s regular population of 3000 male undergraduates had fallen to just 1000 students and in 1917 it was as low as 350. In their place came officer cadets, refugees and growing numbers of wounded.

“Cap and gown have given place to khaki, and to “Kitchener’s blue”, for we have some 3,000 soldiers billeted among us. Twice or thrice daily they march through our streets, sometimes lightfooted, with whistle or song, others wearily shouldering pickaxe and spade. We wake and take our meals to the sound of the bugle; waking or sleeping, reading, or “coaching,” “Form Fours” echoes in our ears. The wounded, whether convalescent or in ambulance, are a familiar sight; the Red Cross floats from the Schools, the Masonic Hall, the Town Hall, and Radcliffe Infirmary.”

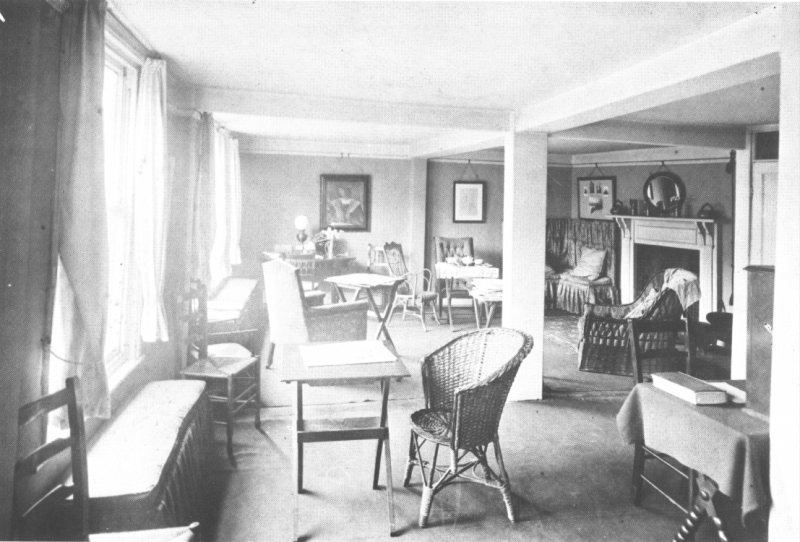

The Ship (1914)

Port Meadow became an aerodrome and the University Parks (save for the sacred cricket pitch itself) was dug and redug into training trenches for cadets. Somerville was requisitioned for a military hospital and their students moved to Oriel for the duration of the war.

The Society of Oxford Home-Students (as St Anne’s was then known) had no great premises to give up. The Woodstock Road site wasn’t acquired until the 1930s and in these early days, the Society’s only shared premises was a rented common room on Ship Street. Nevertheless, the war was keenly felt in other ways.

Society student numbers fell from a peak of 104 in Trinity Term 1914 to 84 in Michaelmas Term as foreign students tailed off; by 1916 there were just 67. Vera Brittain writes in The Women at Oxford of students falling into three categories:

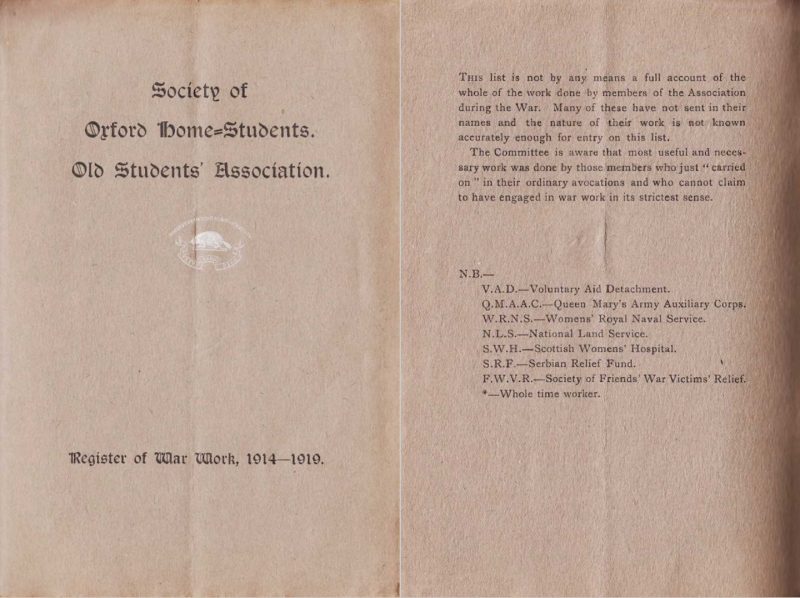

First were those who had just finished their studies when war broke out, and who were able to leave immediately for jobs in government administration, hospital units and later Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps, WRNS and the Women’s Land Army.

Second were the students who found it intolerable to be going about an ordinary life in Oxford waiting for news of their friends and relatives who were serving and dying in the armed forces. Leaving their studies temporarily or even permanently unfinished, they too left to engage in war work.

Third and most numerous, were the remaining students who chose to stay in Oxford and make what they could of their situation, finishing their study for Schools and fitting what war work they could around this, though “it was hard to concentrate on study when the world was crumbling around us”.

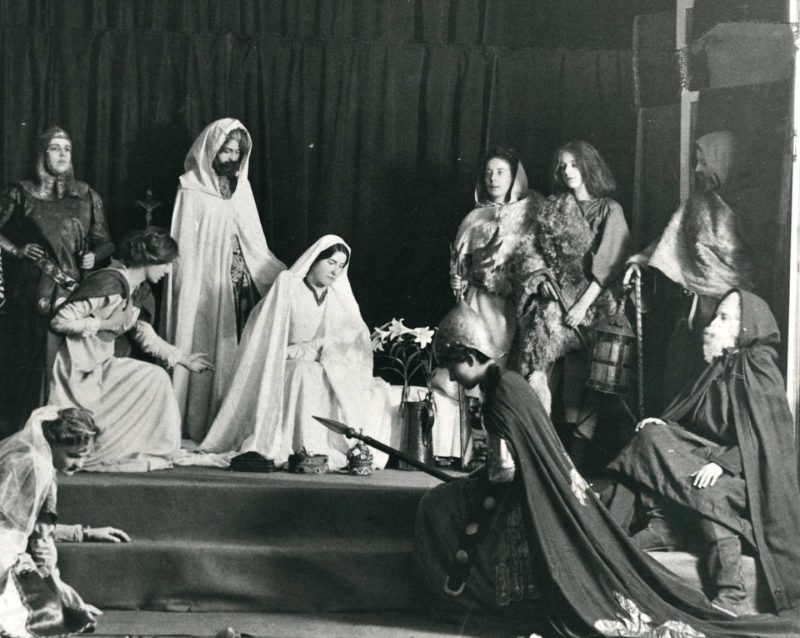

For those students who stayed, routines carried on much as normal. Social gatherings contended with lesser numbers and somewhat diminished rations but clubs and societies flourished. Amateur dramatics were particularly in vogue during the war; writing and the rehearsals being a good distraction.

Women knitted during their lectures and dug up waste spaces for vegetable patches in lieu of games afternoons, while regular lectures and hymn singing in the Sheldonian helped to boost morale. Two lectures by Mr. Fisher and Prof. Gilbert Murray were notable for their inspiration value in extolling the virtues of teaching and the importance of the work that Oxford’s young women could do in training for careers in education. Vacations were spent in strenuous bouts of fruit picking, hopping and working on the land. Students made efforts to visit the wounded in Oxford’s hospitals, wheeling them out for fresh air and rousing spirits with their company. They contributed to relief parcels for prisoners of war and, on one occasion, rallied together to respond to a call for books from a former student working in a French school.

“The chronicles of Oxford and of the Home-Students seem rather “small beer” at the moment that we are all setting our teeth for the hardest struggle of the War. We have learnt to endure without crying out, and to hold fast the hope of an ultimate spring; but in midwinter the birds are silent, nor do thought and feeling overflow easily into words.”

The Ship (1917)

Miss Sandeman, a Home-Student mathematician, paused her studies in 1917 to work alongside two other Oxford women at an aerodrome where new inventions were to be tested. Others became heavily involved in work with Belgian refugees, of whom there were some 500 in Oxford by 1915.

Two Home-Students were killed during the war. Miss Doyle, a geography student, was on board the Leinster when it was torpedoed off the coast of Ireland in October 1918. Miss Chagrin, a Russian national, had left to join the nursing effort and was killed by a shell on the Russian front. Although international student numbers had tailed off sharply during the war, the community of Old Students was cosmopolitan and The Ship from the war years contains many (and refers to more) letters of goodwill and peace from around the world, including Germany.

The 1917 The Ship lacked its until-then distinctive blue cover and had been so reduced by the economies of war that it stretched to only 14 pages, omitting the usual lists of members and containing little more than the ‘Oxford Letter’. Life grew very grim indeed when the influenza epidemic appeared and threatened to claim the lives of those spared by the war.

“The dread influenza epidemic was at its height when Tom boomed forth the news of Peace on that wonderful 11th of November. Our great bell had shared the trials of war with us. His winter curfew had been hushed by fear of air raiders, but his voice had called us daily at noon to prayer for our soldiers and sailors. We listened silently to the solemn news. When the great tolling ceased, the hush was broken and the bells of all the churches burst forth. The War was over, and for the moment we gave ourselves to joy.”

The Society of Oxford Home-Students: Retrospects and Recollections (1879-1921)

In the year after the war, Oxford sprang back to life with renewed vigour. Colleges strained at full capacity as soldiers returned to finish their studies and a generation of young men and women arrived with hope for a new era. The Society of Home-Students in 1919 numbered 168 students, far higher than it had ever reached before the war.

The war work which so many women had undertaken helped to contribute to the first moves for universal suffrage as 8 million women gained the vote. In Oxford, it would be ammunition to defeat what resistance remained to granting degrees for women; though it took until October 1920 for this long held ambition to be finally realised.

Bibliography

- Brittain, V. (1960). The women at Oxford : A fragment of history. London: Harrap. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990110621130107026)

- Butler, R. F. (1957). St Anne’s College : A History : 1879-1953. Oxford: St Anne’s College. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990134226860107026)

- Society of Oxford Home-Students (1911-). The Ship. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990123740420107026)

This article was written and researched by Duncan Jones (Reader Services Librarian).