1902-1948

Dorothy Bowers

The most infamous loss of Golden Age detective writers is that of Agatha Christie. Her 12-day disappearance in December 1926 made headlines up and down the country.

Yet hers was a rather ineffective vanishing. The episode catapulted her further into the limelight and cemented her as one of the nation’s most beloved authors. A true disappearance is more like that of Dorothy Bowers, a contemporary of Christie whose early death from Tuberculosis in 1948 led to her becoming almost entirely forgotten before the recent reprinting of her novels. Despite this recent resurgence, still today no photo of Dorothy is known to exist.

Piecing together what little information is available about Dorothy from various sources, this blog post attempts to uncover forgotten details about the short life of an intriguing woman and under-celebrated author.

Early Life and Education

Dorothy Bowers was born on June 11th 1902 to Albert Edward Bowers and Annie Marie Dean, both locals to Hereford who settled with their young family in Etnam Street, Leominster. Albert was a confectioner by trade and Annie didn’t list any profession in either the 1901 or 1911 census, suggesting that she worked in the home to manage the family and raise the children. Dorothy’s older sister, Gwendoline was also born in Leominster, roughly five years beforehand.

The family relocated when Dorothy was just one, to Monmouth, where Dorothy’s younger sister, Evelyn May (known to the family as May) was born a year later in 1904. By 1911 the family is listed as living in a 6-room dwelling on Agincourt Square in Monmouth along with Dorothy’s paternal grandmother, Anne.

Their house would have looked out over Shire Hall, a Grade I listed building that was at the time the location of the assizes courthouse. One can imagine a young Dorothy peering through her window to watch policeman, suspects, and judges traipse in and out through the courthouse doors, and the seeds that may have sown in a growing mind. Although Agincourt Square also held a WHSmith library ready to foster a love of literature in the young Dorothy, it seems that she favoured the “exciting and catholic jumble of books” that made up her father’s private collection when searching for formative reading material.

Dorothy also credited much to her early education, first from 1909-1913 at a private French convent school, St Mary’s Convent Monmouth, where she claimed to have acquired “method, precision, and an abiding delight in the formal and orderly arrangement of ideas”. She then spent a year at Intermediate School before moving to Monmouth High School for Girls from 1914-1922, where she clearly excelled, as they provided her with an Exhibition scholarship of £40pa (almost £2000 in today’s money) which was required to help fund her studies at Oxford.

Admissions Woes

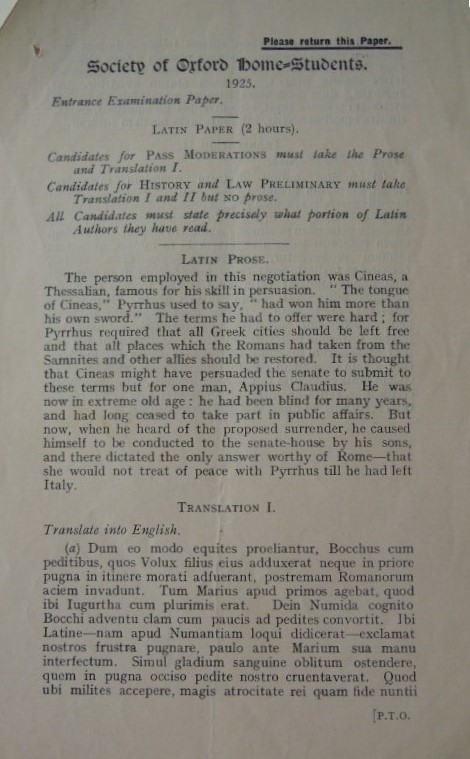

Dorothy faced significant hurdles in her journey to secure a place at Oxford, despite receiving a scholarship. Initially applying to study Modern History at St Hugh’s College in March 1922, she failed the Latin exam both for entrance to the College and for the University’s infamous ‘Responsions’. She was told it was unlikely she would be given a place, even should she resit her tests and pass.

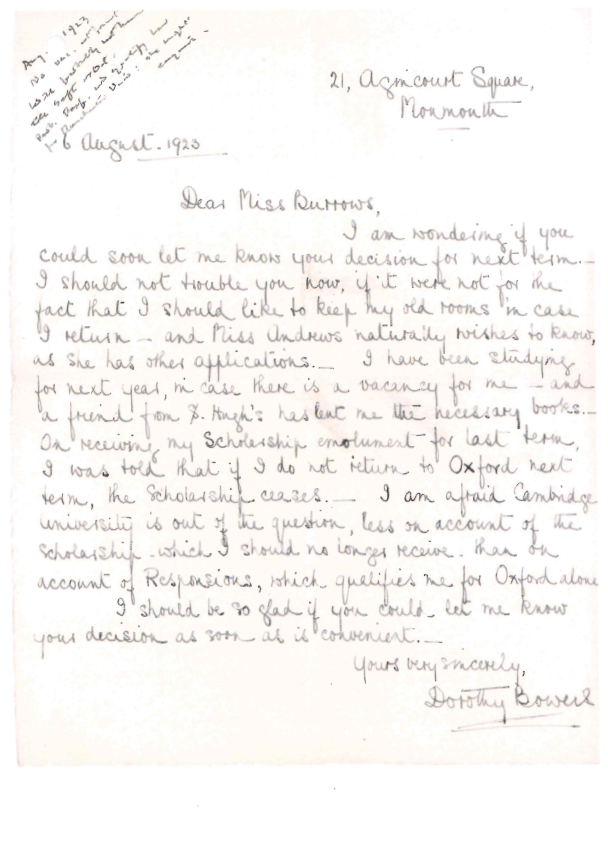

Enter St Anne’s, then the Society of Oxford Home-Students. Dorothy reached out to the principal, Miss Burrows, in July. Entrance requirements for the Home-Students were previously less formalised, involving an interview and correspondence with the former principal Mrs Johnson. Yet the recently instated Miss Burrows had introduced a more formal system of entrance examinations in 1921, just a year prior.

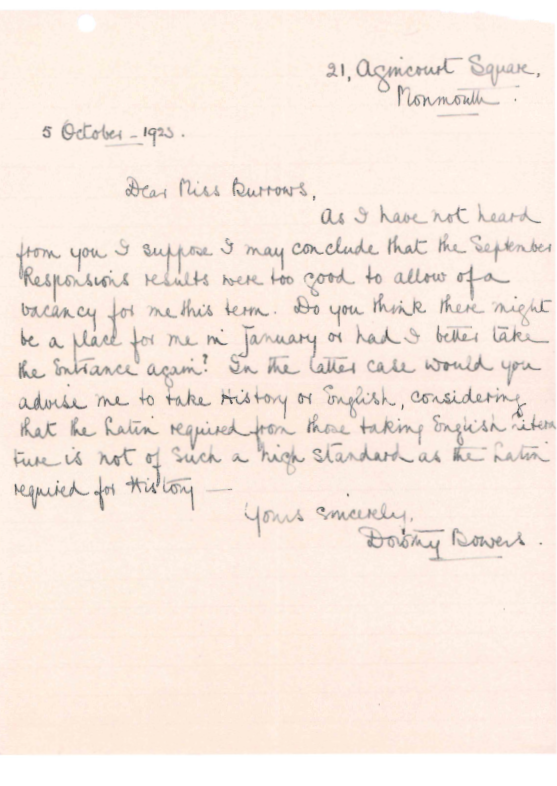

In her letter, Dorothy hopes that her college entrance for St Hugh’s might suffice in lieu of the new exam. However, she was unsuccessful in persuading Miss Burrows to forgo the test. After sitting the requisite papers, in May 1923 she was told there was no place for her once again; in fact, a note scribbled in the corner of a later letter suggests that she was “low down on [the] waiting list”.

Dorothy’s tenacity shines through her correspondence. Despite Miss Burrows’ suggestions of alternative institutions, such as Cambridge and Manchester, Dorothy lists both the restrictions of her scholarship and her previous efforts in the Oxford-specific Responsions as reasons why these would not be suitable for her situation.

Lodging in Oxford, with other women students at 9 St Margaret’s Road, Dorothy ended up spending the academic year of 1922-1923 receiving coaching to pass her Latin Responsions exam, which she finally did in December 1922 (after numerous resists). In October 1923, fearing another rejection, Dorothy sought advice from Miss Burrows, even contemplating switching to English from History. Thankfully, within the day, she had received an offer from the Society of Oxford Home-Students.

Oxford Life

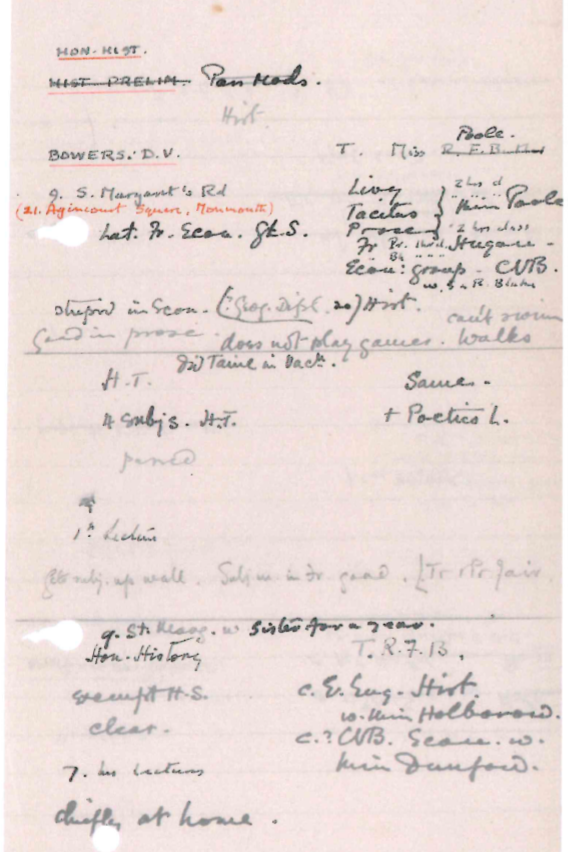

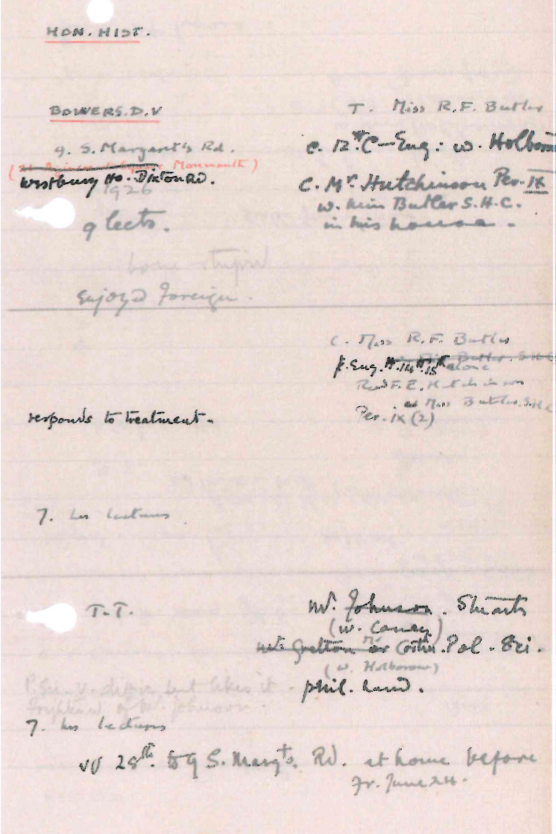

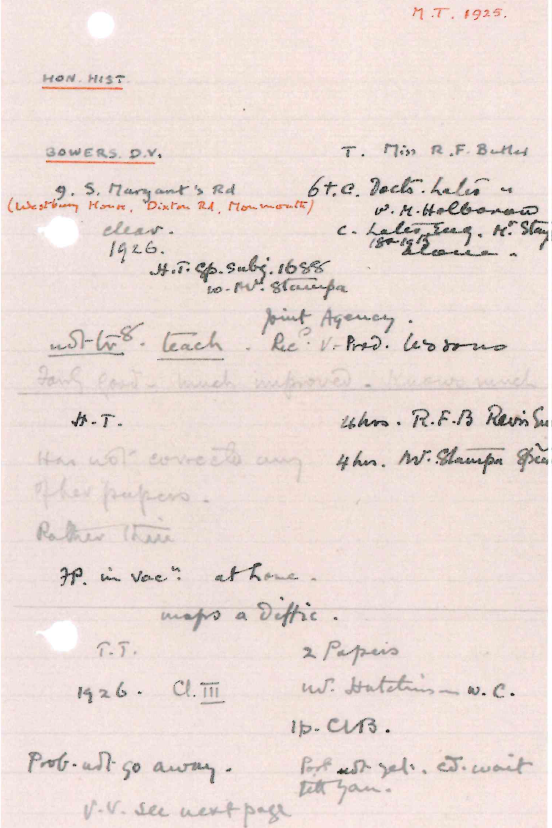

Little information is available about Dorothy’s activities during her time in Oxford. Her student record primarily consists of administrative notes and academic assessments, shedding minimal light on her experiences.

We know she continued to live at 9 St Margaret’s Road overseen by hostess Mary Andrews, who communicated with the principal, Miss Burrows, regarding the students’ welfare. Despite positive feedback from Miss Andrews, who noted that the girls in her care “are very keen about their work & are quite happy in doing it,” Dorothy’s enthusiasm for her studies, and her academic performance, were mixed.

Some tutors were, at times, rather insulting in her student report, with one claiming her to be “stupid in Econ” and another “bone stupid”. Some of this may be due to her own lack of studiousness as another tutor notes that she “has not covered any of her papers.” Others acknowledged her improvement and interest in certain subjects, with one tutor noting that she found “P[olitical]Sci[ence] v[ery] difficult, but likes it”. Kinder tutors stated that she “[r]esponds to treatment” whilst another deemed her “fairly good – much improved – knows much”.

While Dorothy’s academic achievements were deemed average, her younger sister, May, excelled at Oxford after she arrived there to study a year after Dorothy. May, perhaps on Dorothy’s advice, elected to study English rather than History and graduated with a first-class degree in English a year after Dorothy received a third-class Honours degree in Modern History (degrees were then classed as first, second, third, and fourth, so a third would still have been a respectable degree to achieve).

Further Struggle

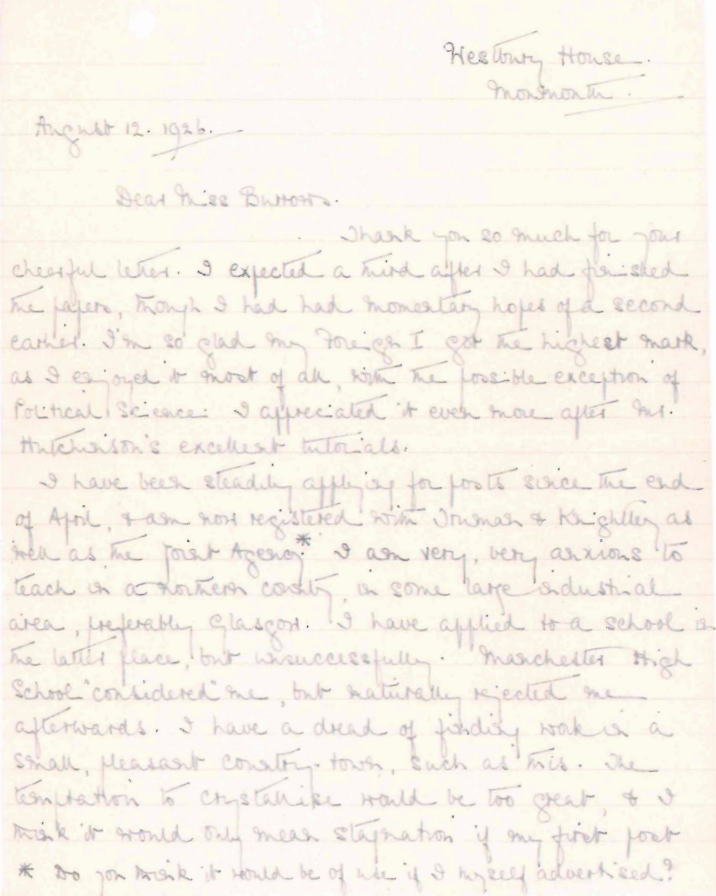

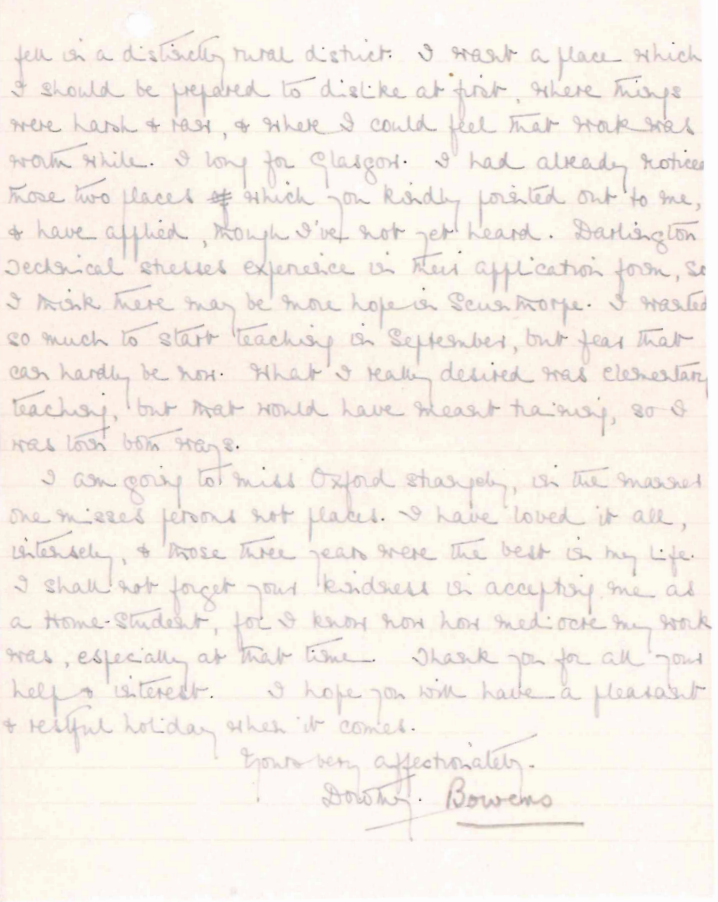

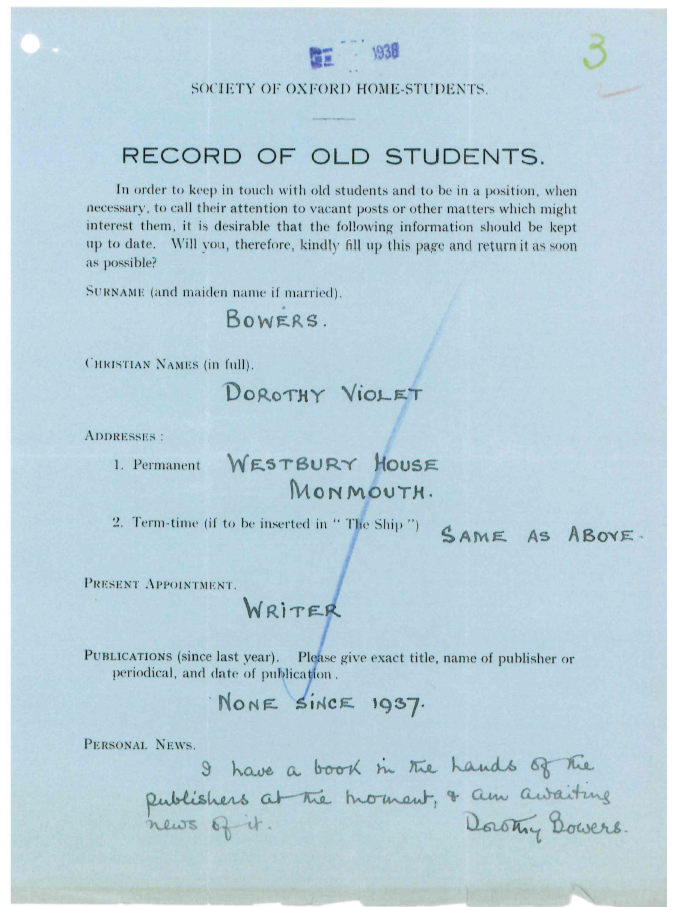

After graduating, Dorothy embarked on a quest for teaching positions, seeking advice from her former principal through numerous letters. Reflecting on her university years immediately after her graduation, she fondly recalled her time in Oxford but acknowledged her unexceptional academic performance. She also expressed a desire to teach in an industrial area like Glasgow, wary of stagnating in rural settings similar to her home town in Monmouth.

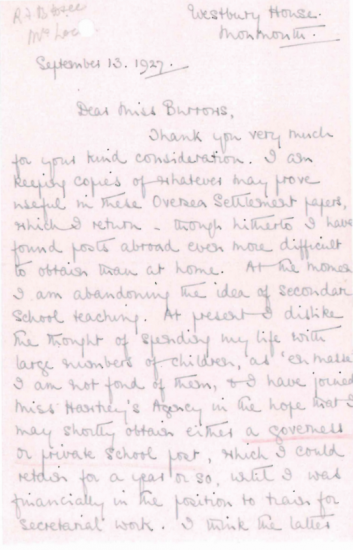

As part of the first generation of women to graduate from Oxford University, Dorothy’s employment options were limited. Like many educated women at the time, she gravitated towards education as a career path. Her first position after graduating was as a cover teacher back at her old High School in Monmouth. What subject did she teach? Latin, of course! Albeit, with little enthusiasm. She admitted, “[a]t present I dislike the thought of spending my life with large numbers of children, as ‘en masse’ I am not fond of them”.

Dissatisfied with secondary school teaching, she explored opportunities as a governess or in private schools to support herself and potentially allow her to pursue secretarial training, though was mindful of the financial strain this training would incur upon her family. Despite her scholarship, the expenses of her education had weighed heavily on her father. Seeking autonomy, Dorothy voiced her desire to forge her own path, saying, “at present I want independence more than anything else”.

However, securing permanent work proved challenging. She “taught intermittently at a boarding school” and “was governess to a succession of children”, but found little satisfaction in teaching. She also never seems to have travelled far from home, we know she made it to Malvern where she taught history, English, and elocution, but that is barely an hour’s drive from her home town in Monmouth. She also taught occasionally at the local girl’s school and tutored the son of the Geography master at the boy’s school in Monmouth.

In addition to not offering her the opportunity to travel, teaching also seems not to be a profession in which Dorothy excelled, she later claimed she “learned more … from spasmodic and unsuccessful efforts at teaching than ever she imparted”.

Perhaps abandoning her ideas of secretarial work, during this period, Dorothy began writing; with her first published work, a short story called “The Spy at Chateau Bas”, appearing in The English Review in 1927. She also wrote a number of poems and embarked on a biography project for Robert Harborough Sherard (himself a biographer and staunch defender of Oscar Wilde). There was a brief correspondence between Dorothy and her subject, as he was still alive at the time, but in the end the biography was never completed.

Despite aspirations towards a literary profession, Dorothy faced rejection and setbacks. In 1931 she wrote to an old friend from Oxford that she still hoped “to make creative literary work my career” but admitted that “it’s a slow, uphill” battle. In fact, she admitted that her mail included “a fairly regular spate of rejection slips from various editors.”

Things were no better in her home life, as at the end of this period tragedy struck the Bowers family. In 1936 Dorothy’s older sister, Gwendoline, aged just 39, died suddenly in the family home.

Just a year earlier, Bowers had written an almost prescient poem, published in The Observer:

Arterial Road

Let us

Be quiet now:

These ways are dead

To pool and primrose bed

Where Pan once beat a road.

Irreticent now they grow where

larches showed

against a winter sky, since here

Murder hath hewn his way,

and life lies shuttered

in a tomb

this day.

The same year that her sister died, Dorothy embarked on a new career path as a crossword setter, contributing to John O’London’s Weekly under the pseudonym ‘Daedalus’. Her knack for analysis proved beneficial, as she later also set crosswords for Country Life Magazine when their former correspondent joined the Navy.

At the same time, Dorothy began reconnecting with the Society of Oxford Home-Students, expressing interest in joining the Old Students’ Association, and receiving a subscription to The Ship, the Society’s alumnae publication.

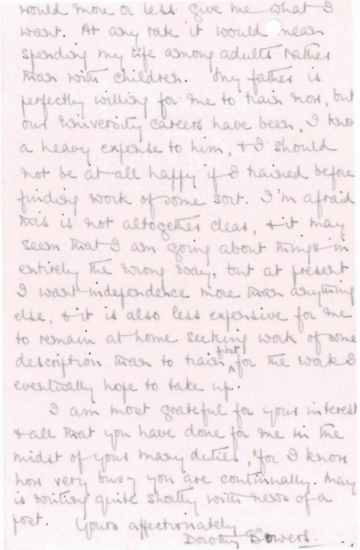

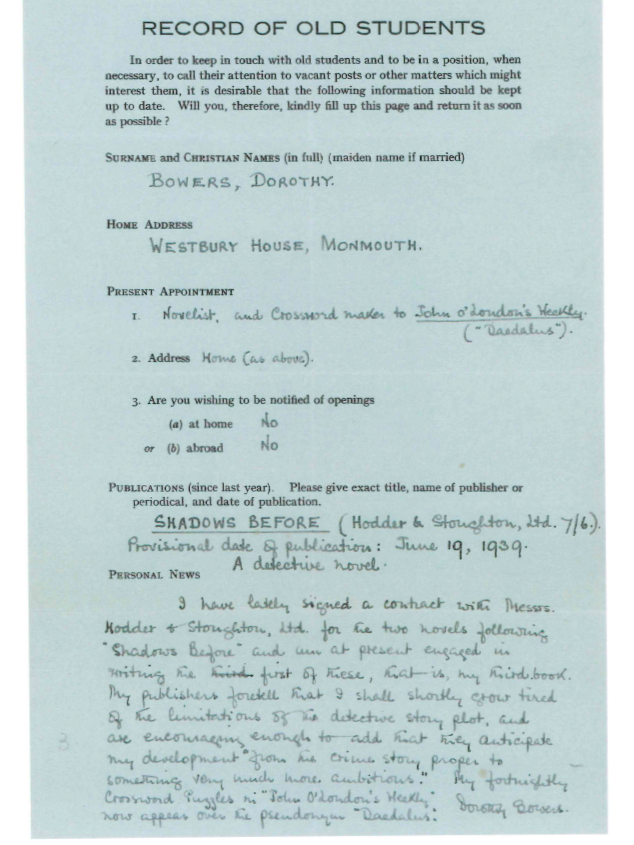

With the submission of her first manuscript to the publishers, Dorothy proudly identified herself as a ‘writer’ for the first time on her ‘Record of Old Students’ form in 1938, anticipating the publication of Postscript to Poison later that year. The novel received favourable reviews, with critics lauding the book as “vividly written; the characters come alive”. Another reviewer predicted Dorothy’s success: “Miss Dorothy Bowers, if her succeeding books maintain the level of her first, should make a name in detective fiction.” Perhaps the chance to finally take pride in her work was what drew Dorothy to reconnect with her old university.

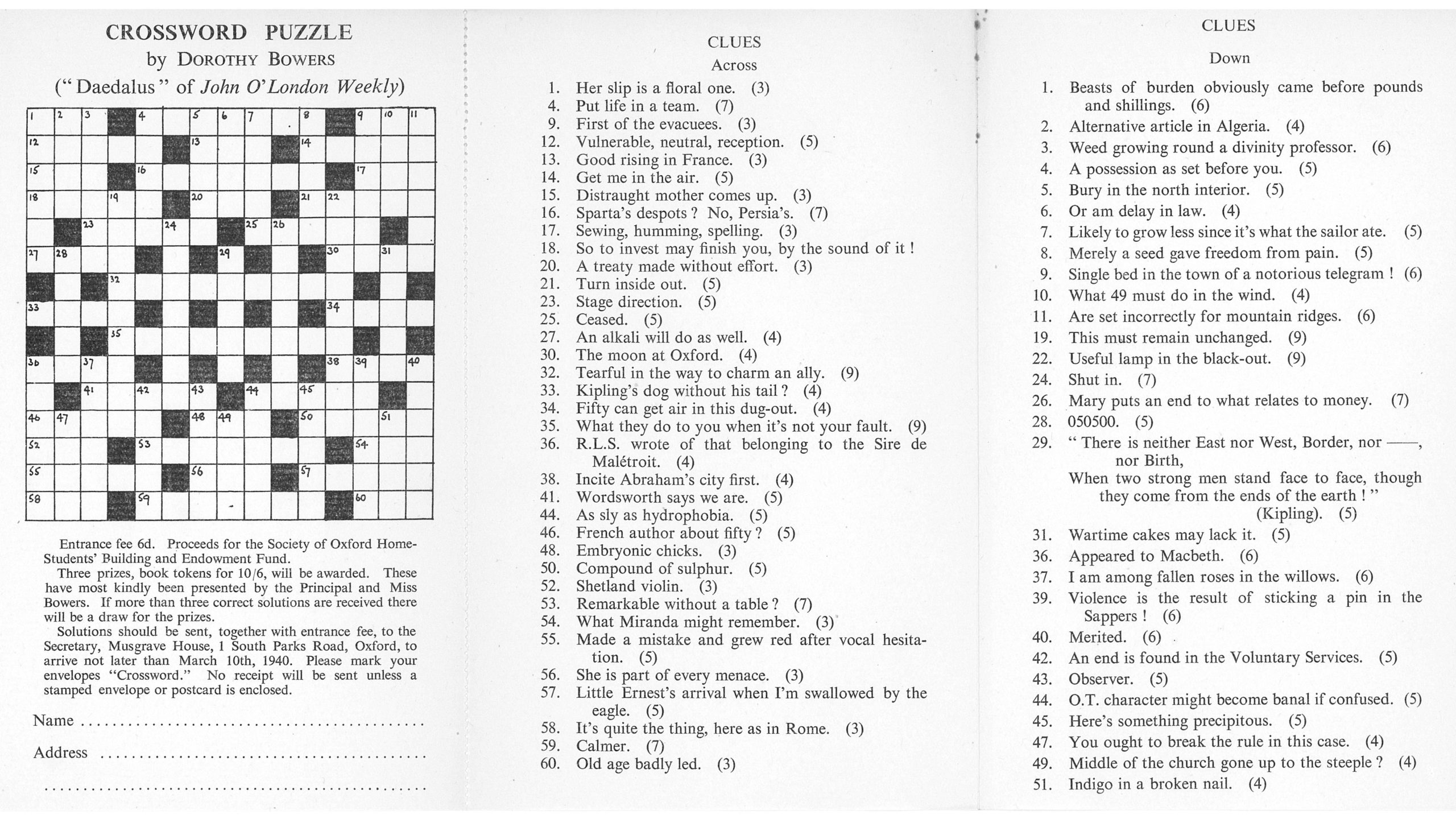

The reconnection was a fortuitous one as, in 1939, Dorothy offered her assistance to the Society’s fundraising efforts by composing a crossword puzzle for their Building & Endowment fund. Despite setbacks following the sudden passing of the new principal, Miss Hadow, the puzzle and Dorothy’s donated book-token prizes were included in the 1940 edition of The Ship, distributed to over 800 alumnae.

These years marked Dorothy’s most productive period, with the release of her second novel, Shadows Before, in mid-1939. This work also received positive reviews, with one reviewer paying it the complement that “it is really competently written and … the thread of detection is straightforward and well planned, with absolutely no cheating.” The novel’s success secured her a contract with Hodder and Stoughton for two more books in the series, as she explains in her next ‘Record of Old Students’ form sent in to the Old Students’ Association.

Below is a copy of Dorothy’s cryptic crossword from the 1940 edition of The Ship. See if if you can solve it yourself and check the ‘solved’ tab for the correct answers.

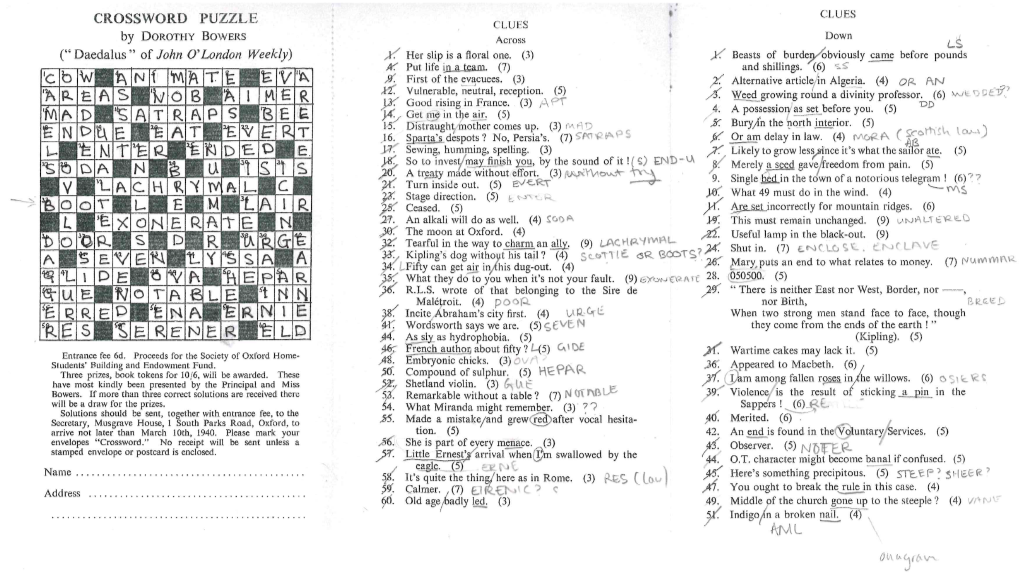

The correct answers to Dorothy’s cryptic crossword from the 1940 edition of The Ship. Kindly solved by the Library Team, with special thanks to Lizzie Dawson.

The War

In September 1939 Britain declared war on Germany, and stringent record keeping became far less of a concern, making the job for modern day historians that much more difficult. We know that Dorothy spent the beginning of the war back in Monmouth, thanks in part to the oral history account of Rita Doughty (née Kohler) an evacuee. Rita recalls how she and another girl, Sylvia, were taken in after arriving at Monmouth’s May Hill Station. The pair formed a friendship with ‘Auntie Dorothy’ and Rita, who was only nine when she arrived in early 1941, recalls getting Bowers to autograph other girls’ books as a way of making friends. Rita and Sylvia didn’t stay long however, as only 13 months after their arrival, Dorothy’s father fell ill, leading to them being relocated with other families nearby.

During this early period of the War, Dorothy wrote her next two books, A Deed without a Name (1940) and Fear for Miss Betony (1941) the latter receiving significant critical approval. The Times Literary Supplement heralded it as the best mystery of 1941, stating “Every page bears witness to a brain of uncommon powers”. It was also selected by one of America’s most discerning mystery critics of the time, James Sandoe, for inclusion in his Reader’s Guide to Crime, a list of mystery high spots he recommended to libraries for acquisition.

Despite her newfound fame, Dorothy did not publish another book during World War II. Clearly not content with sitting at home and writing, she relocated to London in the Spring of 1942. She is later registered as living at 84 Nightingale Lane, Balham, so presumably this was her address during this period of the War. Over the next three years she successively ran the Enquiries Bureau of the National Book Council (today the National Book League), worked for the War Office, and then from 17th May 1943 to 9th March 1944 was a library assistant with the European News Service (BBC).

Final Years

Following the end of the War, Dorothy returned home to Hereford, residing at 7 Chester Avenue in Tupsley, to be near to her aging mother who was alone after Dorothy’s father died part-way through the war in 1943. Dorothy’s mother who by now was in her late 70s, sadly also died a few years later in 1947.

While caring for her mother, Dorothy continued her literary pursuits, publishing her final novel, “The Bells at Old Bailey,” in 1947. Immersing herself in the mystery writing community, Dorothy joined various societies, including the Society for Psychical Research, the Ghost Club and the prestigious Detection Club. This was a group formed in 1930 by a group of mystery writers who embodied the Golden Age of detective fiction and whose current roster included 3 of the latterly dubbed ‘Queens of Crime’, and literary greats: Agatha Christie, Dorothy L Sayers, and Margery Allingham. Invited by Dorothy L Sayers herself, Dorothy Bowers became the sole writer elected to the Detection Club in 1948, marking a significant achievement in her career.

In addition to meeting for dinners and helping each other with their work, the members of the club agreed to adhere to certain fair-play ‘rules’ in their novels and were also required to take part in a fanciful initiation ritual with an oath written by Sayers:

“Do you promise that your detectives shall well and truly detect the crimes presented to them using those wits which it may please you to bestow upon them and not placing reliance on nor making use of Divine Revelation, Feminine Intuition, Mumbo Jumbo, Jiggery-Pokery, Coincidence, or Act of God?”

Expressing her delight in a letter to a friend, Dorothy emphasized the importance of this recognition by her peers: “This pleases me very much, as membership is by invitation only and marks a sort of crowning achievement in this line of work … Much as I’d welcome greater financial success for my books, I do appreciate still more this recognition by fellow craftsmen”.

We know that by this point, Dorothy was already pretty severely ill. Despite her declining health, she eagerly anticipated participating in the club’s initiation ritual. “If the doctor and I between us can get me moving by then I certainly look forward to being present”, she writes. Thankfully she was able to attend her induction as she proudly lists herself as a confirmed member of the Detection Club in the 1948 copy of The Ship.

Tragically, Dorothy’s life was cut short by tuberculosis just a few month later on 29th August 1948, at the age of just 46. Dorothy’s belongings, including any potential manuscripts or notes, were inherited by her younger sister, May, who had gone on to have a successful career as a teacher and later headmistress. Her subsequent passing left the fate of Dorothy’s personal effects unknown.

Legacy

Dorothy’s early death has robbed us of the potential for a whole body of work, perhaps even one that moved past the detective fiction genre as predicted by her publishers back in 1939. As it is, the five books we do have are of undeniable quality. She was rightly recognised by her contemporaries for her skill, and likened to other literary greats such as Dorothy L Sayers, with one reviewer simply stating: “She ranks with the best”.

Sadly, it seems that as the years wore on and the Golden Age of Detective Fiction faded into the past Dorothy’s works were largely forgotten and had remained out of print for decades before the intervention of a small but well-regarded independent publisher run by a married couple of Golden Age detective fiction fans from Boulder in Colorado. Rue Morgue Press, re-published all five of Dorothy’s novels in 2005 bringing her back from the edge of obscurity.

Although Rue Morgue Press themselves have sadly since closed their shutters, Dorothy’s books refrained from disappearing back into insignificance. In 2010 The Independent published a series of short pieces by Christopher Fowler, thriller writer and dramatist, devoted to the subject of “forgotten authors.” Dorothy Bowers made this list, reintroducing her to a wider audience of readers.

A few years later, her books were republished in 2019, this time by the UK publisher Moonstone Press another independent publisher of classic crime novels. Hopefully a recent resurgence in popularity for what is now classified as ‘cosy crime’ will help Dorothy and her novels remain a staple of the mystery genre.

A biographical interview reveals that “she once confessed that her ambition was to live near Oxford and the Bodleian Library.” Although fate intervened to deprive her of the life and legacy she might have had, it is a comforting thought that the Bodleian holds all five of Dorothy’s novels, as now does the college in which she used to study.

Bibliography

Dorothy Bowers’ Publications

- Bowers, Dorothy, ‘The Spy at Chateau Bas’, The English Review, 1908-1937, London, (May 1927 pp.619-627). (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/q6b76e/alma991022148524107026)

- Bowers, Dorothy, Postscript to Poison, London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1938 (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990112883590107026)

- Bowers, Dorothy, Shadows Before, London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1939 (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990112883600107026)

- Bowers, Dorothy, A Deed Without a Name, London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1940 (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990112883610107026)

- Bowers, Dorothy, Fear for Miss Betony, London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1941 (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990112804350107026)

- Bowers, Dorothy, The Bells at Old Bailey, London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1947 (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990112804370107026)

- Whitaker, Frank, and Williams, William Tom Saturday to Monday : A Week-end Companion 2d ed., London: G. Newnes, 1948 (contains three poems by Dorothy Bowers, originally printed in John O’London’s Weekly magazine.) (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990124247270107026)

- John O’London’s Weekly, 1919, London (Bowers set crosswords and published some of her poems.) (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990140096510107026)

- The Observer, 1791, London (Bowers published some of her poems.) (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/q6b76e/alma991022126922207026)

- Country Life, 1901, London (Bowers set crosswords and wrote to the editors.) (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma991022126902907026)

Sources and Further Reading

Books

- Edwards, Martin. The Golden Age of Murder: The Mystery of the Writers Who Invented the Modern Detective Story, London: HarperCollins, 2015 (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990203704850107026)

- Walter, Hugo. Devoted to the Truth: Four Brilliant Investigators. New York: Peter Lang, 2022 (Studies on Themes and Motifs in Literature; Vol. 142.) (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990232715980107026)

- Collins, W. J. Townsend. Monmouthshire Writers: A Literary History and Anthology. Newport, Mon. [Eng.: R.H. Johns, 1945. (Vol. 2. – called More Monmouthshire Writers), pp. 148-153. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990113523940107026)

Archival records

- Society for Psychical Research archive, GBR/0012/MS SPR, Cambridge University Library. (https://archivesearch.lib.cam.ac.uk/repositories/2/resources/13400)

- The Ghost Club archives, Add MS 52258-52273 : 1882-1936, British Library. (http://searcharchives.bl.uk/IAMS_VU2:LSCOP_BL:IAMS032-002001696)

Articles and more

- ‘Dorothy Bowers’ – Moonstone Press biography (https://moonstonepress.co.uk/dorothy-bowers/)

- Schantz, Tony and Edith. ‘Dorothy Bowers’ – Rue Morgue Press biography [archived from the original] (https://web.archive.org/web/20150514101538/http:/www.ruemorguepress.com/authors/bowers.html)

- Fowler, Christopher. ‘Forgotten Authors No 49: Dorothy Bowers’ – The Independent (https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/features/forgotten-authors-no-49-dorothy-bowers-1909505.html)

- Redmond, Moira. ‘The Life of Dorothy Bowers’ – Clothes in Books (posted 2 July 2022) (https://clothesinbooks.blogspot.com/search?q=dorothy+bowers)

- Hall, Matt. ‘Dorothy Violet Bowers, novelist (1902-1948)’ – Random Genealogy (posted 27 July 2021) (https://randomfh.blogspot.com/2021/07/dorothy-violet-bowers-novelist-1902-1948.html)

- Edwards, Martin. ‘Dorothy Bowers and Rue Morgue’, Martin Edwards’ Crime Writing Blog (posted 15 January 2008)

- Evans, Curtis. ‘Women’s Worlds: Fear for Miss Betony (1941), by Dorothy Bowers’ – The Passing Tramp (posted 9 February 2020) (https://thepassingtramp.blogspot.com/2020/02/womens-worlds-fear-for-miss-betony-1941.html)

- Doughty, Rita. ‘Evacuated to Monmouth’ – BBC WW2 People’s War: An archive of World War Two memories (posted 15 June 2005) (https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/98/a4198098.shtml)

- Crampton, Caroline, with guest Redmond, Moira. ‘The Mysterious Dorothy Bowers’ – She Dunnit podcast (aired 25 Jan 2023) (https://shedunnitshow.com/themysteriousdorothybowerstranscript/)

This article was written by Alice Shepherd (Library Assistant), building on research by Lizzie Dawson (Library Assistant).