Bevington Road has been a formal part of the college site since the early 1950s when houses began to be bought up, but has a longer history of housing women students and members of the University. As St Anne’s looks to renovate the houses and bring them up to a modern standard, this blog post explores the history of the Bevington Road site from the medieval period to the present day. You can find more information about the redevelopment at Transforming Bevington Road

St Giles Field

Medieval sources on the 14th Century parish of St Giles describe the land between ‘Banbury Way’ and ‘Woodstock Way’ as a series of fields and the section from St Giles’ Church to what is now Bevington Road as ‘Le Gores’. Local landowners who farmed portions of an up to an acre in Le Gores included William Dageville (one time Mayor of Oxford and Member of Parliament) and tenant farmers of Godstow Abbey.

Over time the greater area North of St Giles’ Church became known as St Giles’ Field, and a 500 acre stretch of this land beyond the city walls was acquired by the nearby St John’s College in 1577.

For centuries, the land would have returned an income to St John’s through tenant farming and livestock grazing. The site of Bevington Road was also excavated as a gravel pit and the gravel used in local construction. This land ownership prevented gradual building development and meant that any increased housing needs of the city were met by the growth of outlying communities such as Wolvercote, Marston and Summertown. In 1854 there were just 487 houses in the whole of St Giles parish.

Mrs Taunt on what is now Bevington Road, 1858. The hollow in the land from the old gravel pits is clearly visible. © Historic England Archive.

By the mid Nineteenth Century, St John’s was beginning to consider other uses for the land and began to stop renewing leases around St Giles when they reached the end of their term. In 1842, Joseph Parker’s lease on the land south of what was then known as Horse and Jockey Road (after the inn on Woodstock Road and fairground entertainments on the site of present day St Antony’s) was not renewed. In 1851, a bill was taken before parliament proposing to extend the Worcester railway line to Brentford in London, cutting across North Oxford in the process. This line would have run almost along the boundary of Horse and Jockey Road and then on through the parks. The proposal was supported by the people of Oxford who saw it as an opportunity to increase wealth and traffic, but opposed by St John’s and the University. Several similar proposals were put forward over the following years but the bill was ultimately thrown out by Parliament.

By 1856, St John’s had almost all of this increasingly desirable land between Woodstock Road and Banbury Road as far north as Canterbury Road back under their control, and by 1865 practically all of the land in the St Giles parish.

The North Oxford Suburb

The rise of a middle class families, with income and a desire for status, drove the development of North Oxford. This demand coupled with the increasing availability of investment funds for leases and mortgages allowed the speculative building of large numbers of houses. In 1862, St John’s College created an estates committee to look after the development and divided the suburb into two areas: one of detached and semi-detached villas for the wealthier middle classes, and another of terraced and other smaller houses for the lower-middle and working classes.

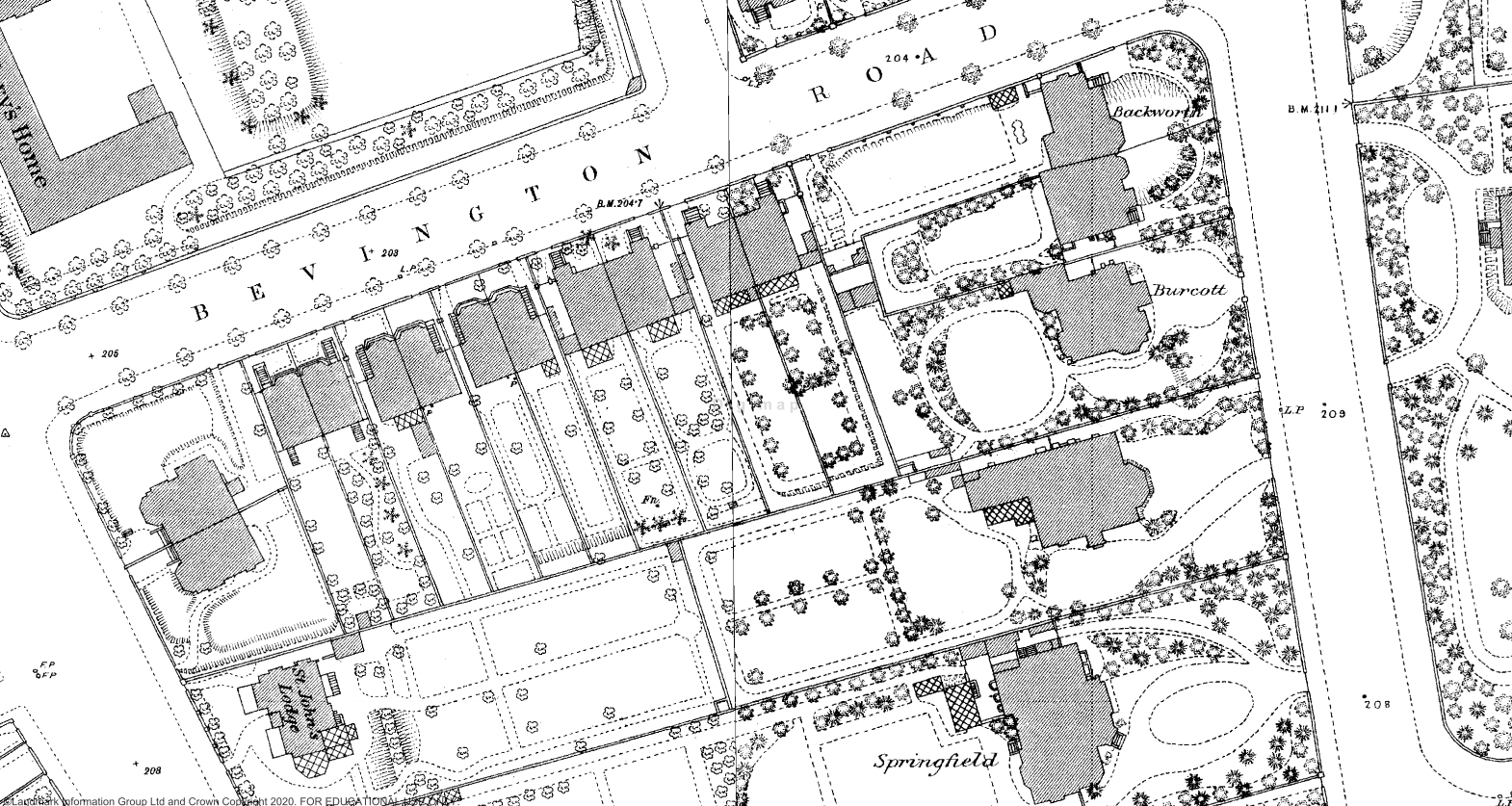

In the early 1860s Bevington Road was being referred to as Jeffreys Lane, after an area of land called Stephen Jeffreys’ Nursery to the north. As part of these master plans for a North Oxford suburb, St John’s sold leases in August 1865 for the plots on the south side of this road.

The same few architects names appear again and again in connection with North Oxford and it was one of these, Frederick Codd, who designed all ten of the houses on the south side of the road. Codd had been a pupil of William Wilkinson, another prolific Oxford architect, and their Gothic Revival architectural styles are very similar. Codd and a builder by the name of Matthew Gray were responsible for the design and construction of:

1-10 Bevington Road (1867-1869)

58 and 60 Woodstock Road (1862)

35, 37, 39 and 41 Banbury Road (1867-1868)

Both 39 and 41 Banbury Road were retained for Codd himself but after his prolific run of speculative building failed to realise the sums required to pay his backers, he was declared bankrupt in the mid 1870s and forced to sell his own home (41 Banbury).

It was around this time that the road was also renamed Bevington Road, after an estate belonging to St John’s College in Warwickshire called Wood Bevington.

St John’s retained a tight control over the character of the area, advising on the style of houses for each plot and requiring permission if trees were to be cut back or felled for building. Mature trees were retained where possible and when the new residents of Bevington Road decided to plant a row of limes on their street in 1871, the college contributed £5 to the fund.

The Residents

The first leaseholders in Bevington Road came from fairly modest backgrounds, something which reflected the smaller nature of the houses, relative to larger villas springing up elsewhere in the suburb. Among those occupying the ten houses were a printer, a printer seller, a college cook, a spinster and a commercial traveller (the delightfully named Sleeman Lovis).

A decade later, in 1877, changes in the University formally meant that dons were allowed to marry for the first time and Oxford began to undergo a period of social change. The fellows who had previously lived as bachelors in college rooms now had need of family accommodation and the Bevington Road houses began to be associated with members of the University. Among them were the economic historian Arnold Toynbee (5 Bevington Road) and Professor of Church History James Vernon Bartlett. Another resident, C. J. C. Price, was the first (recognised) Oxford fellow to be married.

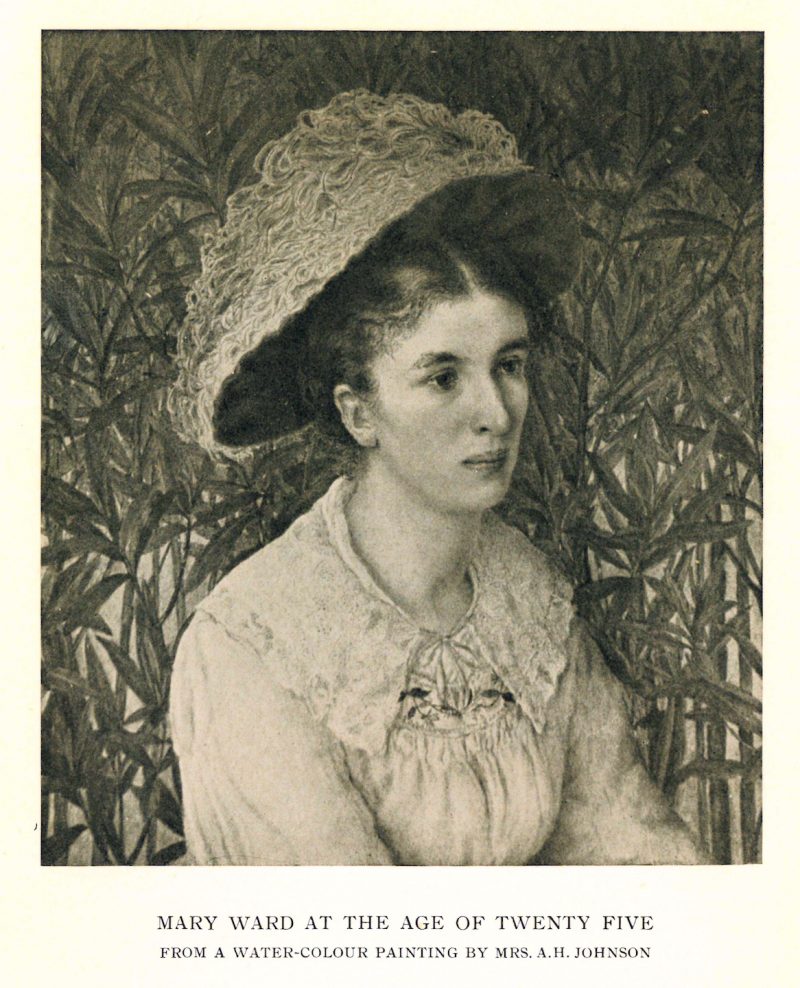

After Arnold Toynbee’s early death in 1883, 5 Bevington Road was home to the Rev. T. D. Lamb and saw frequent visits from Matthew Arnold and his niece Mary Augusta Arnold (Mrs Humphry Ward), who was reportedly drawn walking in the orchards behind the house around this time.

Professor Simpson shared his mother’s house (7 Bevington Road) and the modest rents meant that there were often widows and elderly ladies among the other residents. The widow of the Red Lion’s landlord, Mrs. Pollicott, lived at 1 Bevington Road with her daughters after her husbands death.

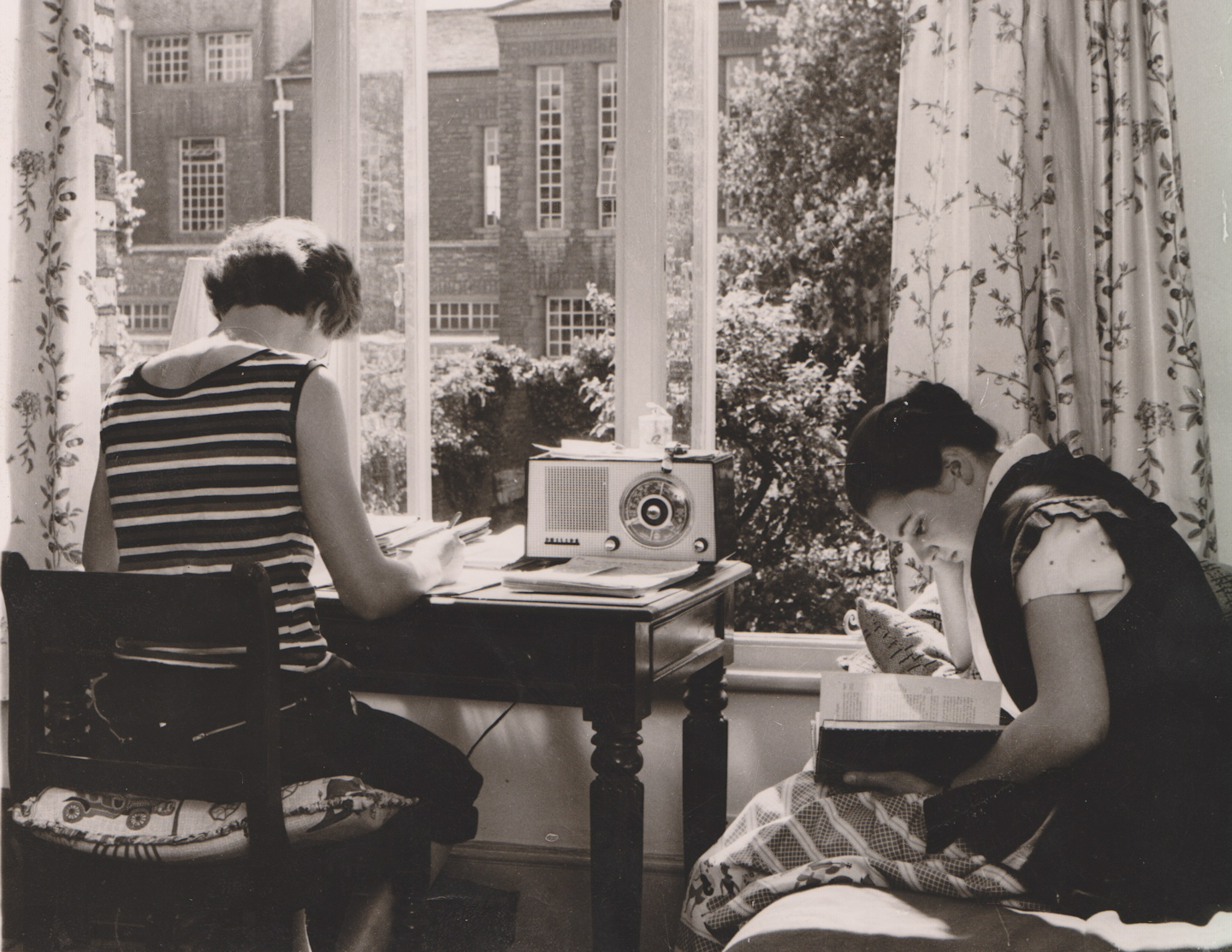

The impact of the First World War, both on the population of young men and on the economic position of the country, saw another social change. The Bevington Road houses, though small by North Oxford standards, were too large to maintain without servants and too expensive for widows on fixed incomes. This change aligned with a rise in women students at the burgeoning women’s halls and societies and saw many leaseholders become landladies as they opened up their homes and former servant’s quarters to women student lodgers.

“My lodging in Keble Road had now been changed for a supposedly superior room in a Bevington Road house…it contained five large mirrors and for this reason had been selected for me by the Bursar… This ground- floor habitation, which faced due north and was invaded at night by armies of large, fat mice, soon became for me a place of horror ; I avoided it from breakfast till bed-time, and if ever I had to go in to change my clothes or fetch a book, I pressed my hands desperately against my eyes lest five identical witches’ faces should suddenly stare at me from the cold, remorseless mirrors.” – Vera Brittain on her time in Bevington Road in 1920.

Later, after the Second World War, the houses were even less financially viable to run and many were converted into flats or what might now be called studios, consisting of a single bedroom and a coin fed meter.

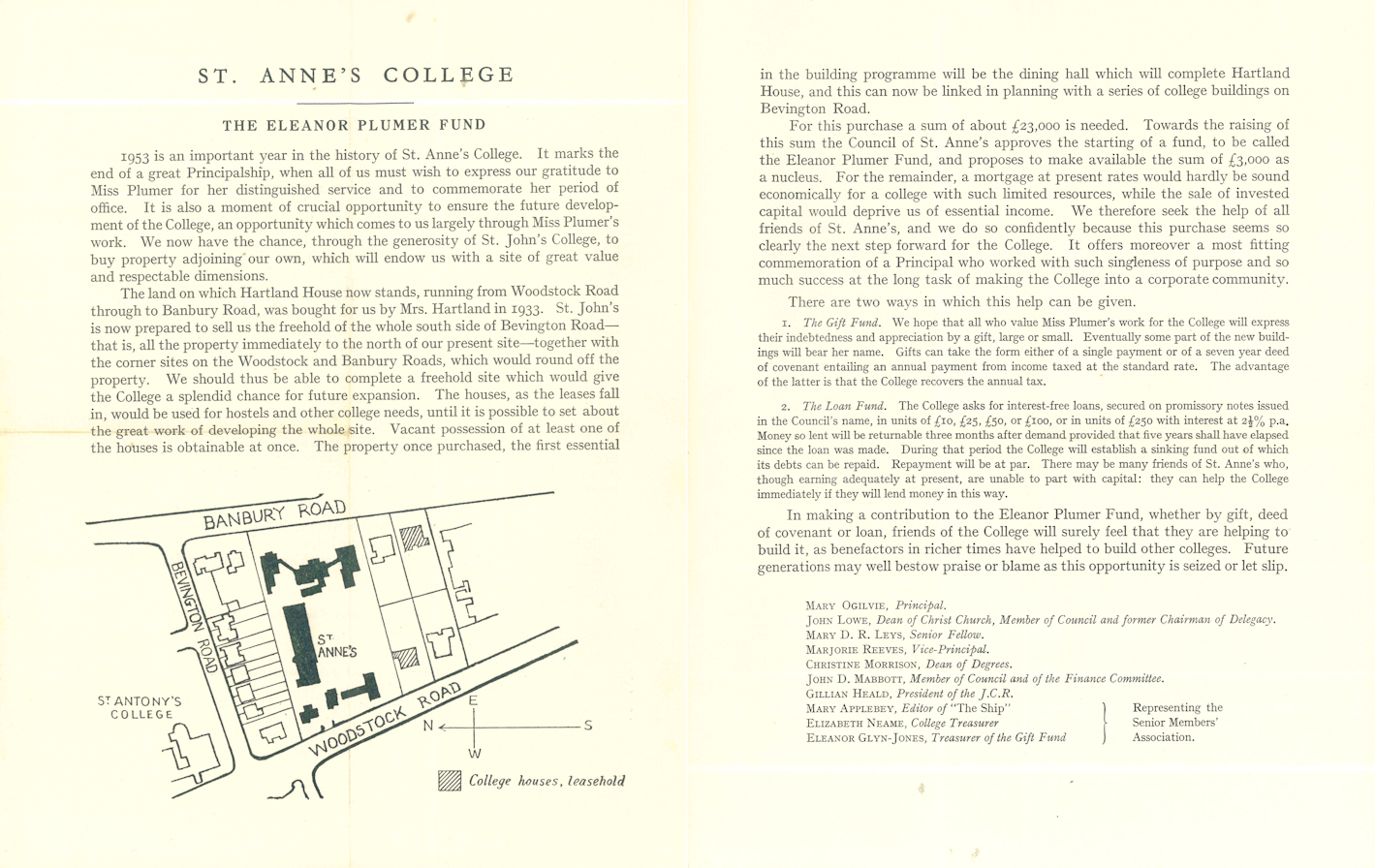

Under St Anne's

The Society of Oxford Home-Students had had a presence on the Woodstock Road site for some time thanks to the accommodation provided at Springfield St Mary, a religious house at 33 Banbury Road. In the late 1930s, 35 Banbury Road and 56 Woodstock Road were acquired by Mrs. Hartland, and Hartland House constructed between their large adjacent gardens. With a library and teaching rooms on the site, the houses of Bevington Road became an attractive prospect for the newly named St Anne’s Society (1942) and a fundraising programme to buy the leaseholds from St John’s in the 1950s saw each house gradually taken over by the College. No. 3 Bevington Road was gained with vacant possession in 1953 while the others had sitting tenants who were gradually replaced by students as the leases expired. The last flat at the top of 6 Bevington Road was taken over in 1963.

The houses provided students with something closer to the traditional college ‘staircase’ accommodation, while also remaining individual with their varied architecture and walled gardens. A typical arrangement would see a tutor, the dean or a caretaker in the ground floor of the house, with students in the rooms above. Iris Murdoch is well known for having had her tutorials in her Bevington Road study, sometimes drinking and offering gin to her students!

“I lived for all my 3 years in 7 Bevington Road in a room above the Dean with her bird-loving ginger cat and next door to the caretaker and his wife who brought a homely normality to college life. I looked out on to Hartland House and some beautiful gardens filled with Keats’ “globed peonies”” – Julie Benson (1976)

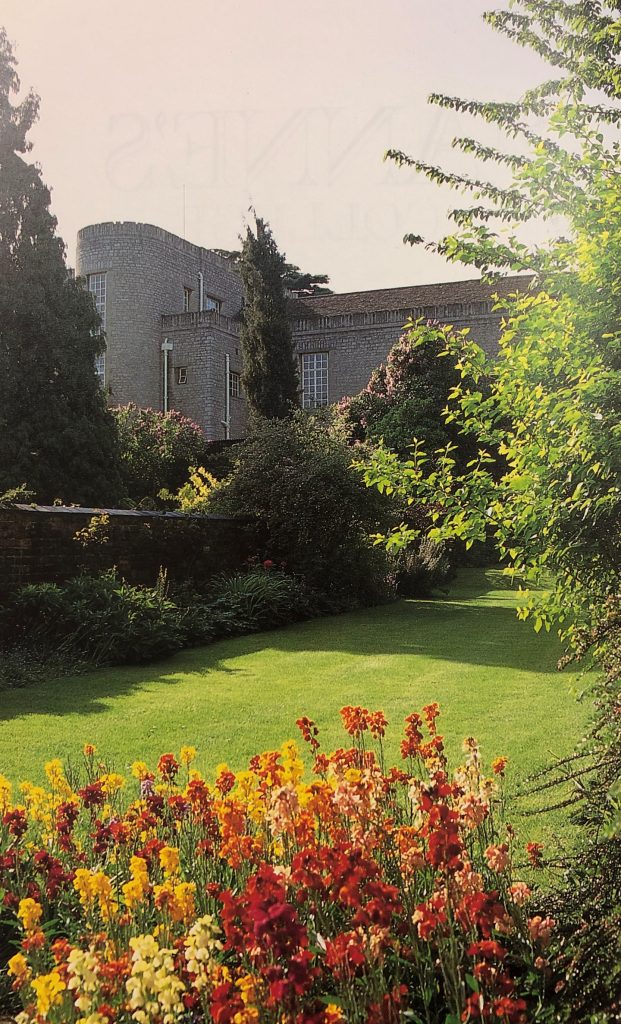

Photos from Bevington Road of the walled gardens from the late 80s and early 90s.

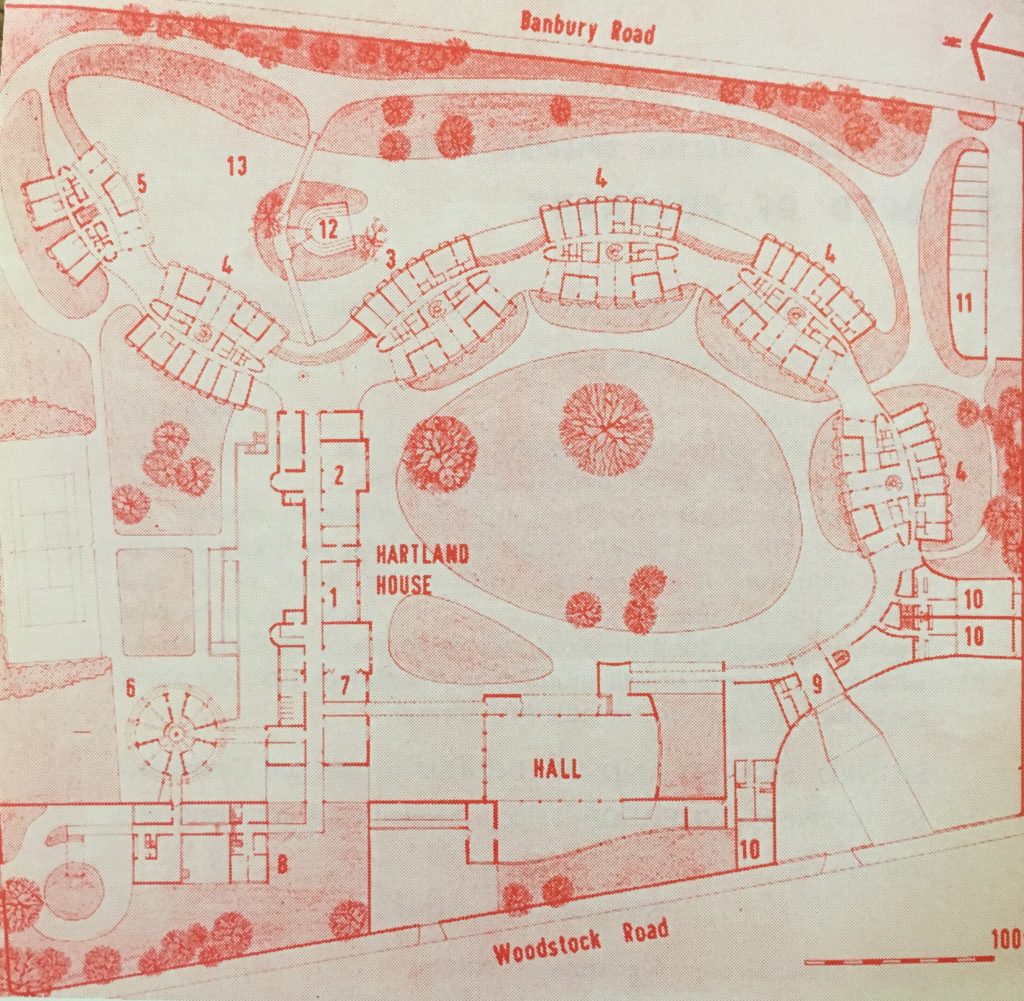

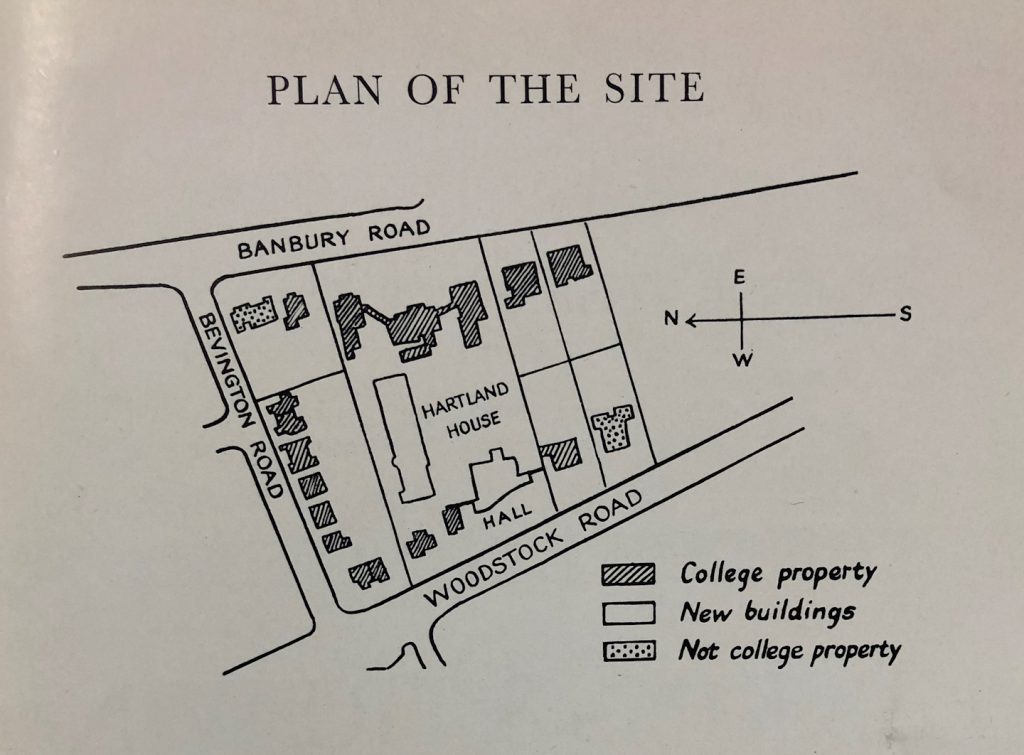

The consolidation of properties in the 1960s also saw the College commission architects to develop a radical and modern master plan for the site. The concrete brutalist plan which eventually culminated in the construction of Wolfson, Rayne and Gatehouse was originally envisaged as a guide for the whole site and including knocking down the Bevington Road houses completely. In the plan pictured below, there is instead a further accommodation block in the North East corner, and a large area given over to a tennis court.

The plan was abandoned for a number of reasons including a financial shortfall but also a strong resistance from a growing conservation movement, which sought to protect the distinctive character of the Victorian suburb.

The masterplan from the 1960s, the architect’s model showing a view from Bevington Road, and a 1960 plan of college property.

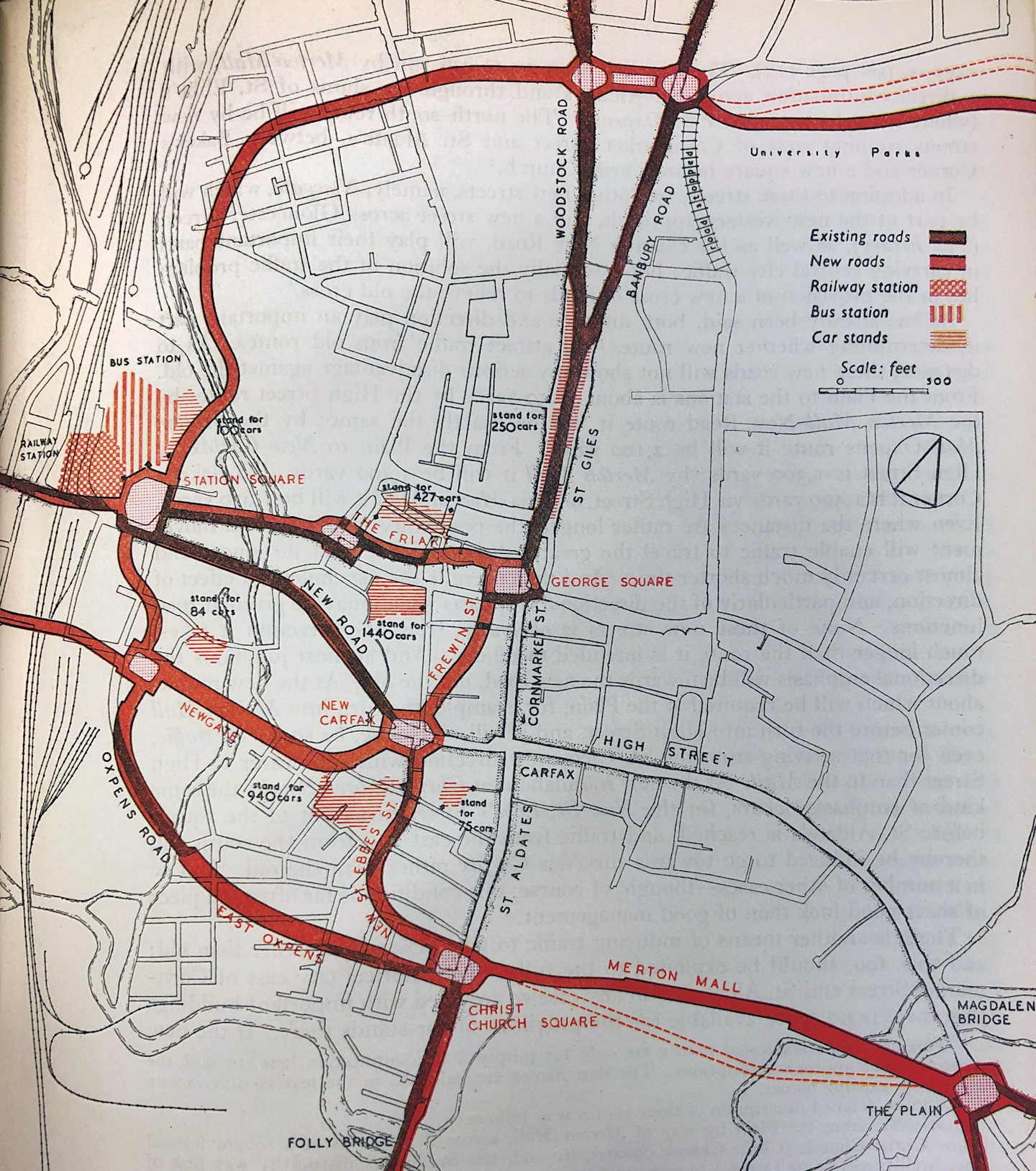

It was not just the college’s own ambitions that affected the future of the houses. In 1956 the Abercrombie scheme (named after Sir Patrick Abercrombie) proposed a traffic management plan for Oxford that involved constructing an interior ring road cutting through Christ Church meadow, Jericho and the University Parks. It would have run either directly through the college site or otherwise along Bevington Road, expanding it into a major artery and requiring some demolition along the North side. Thankfully this, like the railway before it, was heavily opposed and ultimately abandoned, though St Ebbe’s did suffer demolition to make way for the Oxpens road.

In June 1969 St Anne’s petitioned the City Council to rename Bevington Road as Plumer Road in honour of the late Eleanor Plumer who had led the college so well towards the acquisition of the houses. The application was supported by St Antony’s College and the University, but the Council rejected the proposal.

As the years went by and “The Bevs” became a college institution, more architecturally sensitive solutions were being sought for expanded accommodation. The first of these to come to fruition was the construction of Trenamen House in 1995.

A pastiche Victorian building designed by Gray Baynes and Shew, it fitted into a space at the Eastern end of Bevington Road by number 10, in the gardens of 37-41 Banbury Road, and blended in with the surrounding architecture while providing 26 much needed additional rooms and other facilities.

The College’s ever growing need for accommodation found the site being appraised once again in the early 2000s and a plan that saw the low walled gardens between Bevington Road and Hartland House filled in with an impressive 113 student rooms, as well as a lecture theatre and seminar rooms below ground level. The Ruth Deech building was completed in 2005.

The Bevington Road houses are now a protected part of the North Oxford Conservation Area and refurbishing and updating their interiors to bring them into the 21st Century is a high priority for St Anne’s. Internal reconfiguration as well as improvements to the gardens, infills and frontages on Bevington Road will make them more attractive and welcoming for wildlife and our students alike! Find out more about the plans for Bevington Road Regeneration Project by clicking the image below:

Appendix

Original names of the Bevington Road houses, where known, and the census date first recorded:

- Denmark Villa (1871)

- Haslemere (1871)

- Brynrhos (1871)

- None / Unknown

- Woodbury (1871)

- Windale (1871)

- Ferndale (1871)

- Gladtheim (1871)

- Hawthornden (1871)

- Acacia Lodge (1881)

Bibliography

- Brittain, V. (1933). Testament of youth : An autobiographical study of the years 1900-1925. London: Gollancz. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990137835610107026)

- Cole, C. (1962-1967). Some Vanishing Oxford Houses in Society of Oxford Home-Students (1911-). The Ship. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990123740420107026)

- Hinchcliffe, T. (1992). North Oxford. New Haven ; London: Yale University Press. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990105494970107026)

- Oxford City Council (2017?). Conservation Area Appraisal: North Oxford Victorian Suburb (https://www.oxford.gov.uk/downloads/download/32/downloads-for-north-oxford-conservation-area)

- Reeves, M. (1979). St Anne’s College, Oxford : An informal history. Oxford: St Anne’s College. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990123366450107026)

- Sharp, T. (1948). Oxford replanned. London: Published for the Oxford City Council by the Architectural Press. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990101331170107026)

- Smith, D. F. (2012). St Anne’s College, 1952-2012. Oxford: St Anne’s College. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990193279450107026)

- Stevenson, W., Salter, H., Taylor, A., & Baskerville, G. (1939). The early history of St. John’s College, Oxford (Oxf. Hist. Soc. (Series) ; new ser., v. 1). Oxford: At the Clarendon Press for the Oxford Historical Society. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990122638940107026)

- Symonds, A., & Morgan, N. (2010). The origins of Oxford street names. Witney: Robert Boyd Publications. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990173436590107026https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990173436590107026)

- Trevelyan, J. (1923). The life of Mrs. Humphry Ward. London: Constable & Co. (https://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/permalink/44OXF_INST/35n82s/alma990125424370107026)

This article was written by Duncan Jones (Reader Services Librarian).